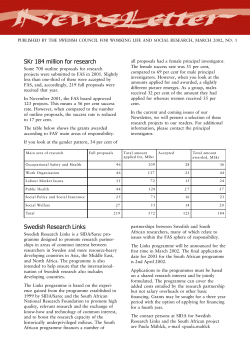

Impact of Trade Liberalisation under the Information Technology Agreement (ITA)... Asian Electronics Industries: A case study of India