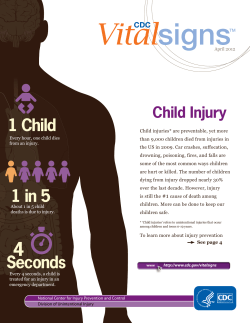

CDC National Health Report: Leading Causes Behavioral Risk and Protective Factors—