Current Issues and Challenges in Vascular Access Device Related Infection Prevention

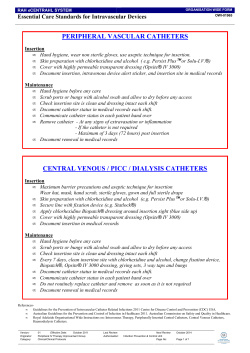

Current Issues and Challenges in Vascular Access Device Related Infection Prevention Lisa A. Gorski MS, HHCNS-BC, CRNI, FAAN © 2014 BD MSS0387-2 (10/14) Disclaimer Lisa Gorski is a paid consultant for BD (Becton, Dickinson and Company). • The development of this presentation was commissioned by BD. • The contents of this presentation are intended for general information purposes only and the views expressed therein are solely those of the presenter and not BD. Objectives • Describe the concept of a care “bundle.” • Discuss evidence supporting the need for postinsertion VAD care strategies. • Identify current issues and challenges related to needleless connector/catheter hub disinfection Presentation Outline • • • • • Overview: Bloodstream infection Success with the “Central Line” bundle More about “bundles” Post-insertion care issues Focus on needleless connector disinfection: current research & issues • Challenges and successes in implementing evidence-based practices • Summary and conclusions Bloodstream Infection • A serious and life threatening complication of VADs • 80,000 catheter related bloodstream infections occur in ICUs annually in USA ▫ 250,000 per year if the entire hospital is included 1 • Little current data to estimate the rate of such infections in alternate sites • Most data related to CVADs; less is known about peripheral IV infections • One of the 10 hospital-acquired conditions considered a preventable adverse event • National Patient Safety Goal 2 -- prevention of CVAD infections for both hospitals and long-term care organizations • A continuing research priority TABLE 2. Estimated annual number of central line-associated blood stream infections (CLABSIs), by health-care setting and year --- United States, 2001, 2008, and 2009 3 Health-care setting Intensive-care units Year 2001 2009 A 58% reduction in ICU CLABSIs in 2009 as compared to 2001 No. of infections (upper and lower bound of sensitivity analysis) 43,000 (27,000--67,000) 18,000 (12,000--28,000) Inpatient wards 2009 23,000 (15,000--37,000) Outpatient hemodialysis* 2008 37,000 (23,000--57,000) * Case definitions approximate current definition of CLABSI according to the National Healthcare Safety Network Home Care & Infection Risk • Risks of infection for patients with VADs believed to be low – scarce recent data • Home care advantages: ▫ Risk of transmission associated with multiple patients/multiple providers in an institution eliminated in the home setting • Home care risks: ▫ Patients more active – bathing, exercising, gardening, playing with pets ▫ Patient/caregiver care of VAD/infusion administration -- may or may not be a risk Patient Risk Factors for Infection – Home Health • Systematic literature review4 • 25 studies met inclusion criteria • Great variation in risk factor identification and infection rates • Infusion therapy ▫ Patients receiving PN at greater risk than those receiving other infusion therapies Survey of Home Care Agencies • Investigation of home care agency CLABSI definitions and prevention policies5 • 25% (14/59) of surveyed agencies knew their overall CLABSI rate (mean 0.40 CLABSIs per 1000 central line days) • Some discrepancies between home care policies and pediatric bundle elements (focus on pediatric care) • Limitations on ability to use sterile gloves, change caps, tubing, dressing changes due to insurance companies Infection Prevention: Catheter-Insertion • The “Central Line Bundle” (hand hygiene, maximal sterile barrier precautions, chlorhexidine skin antisepsis, optimal site selection, daily review of need for CVAD) • Aimed at catheter placement procedures and preventing microbial access via the extraluminal route • Other technologies and additional practices adopted many organizations – examples… ▫ Antiseptic dressings ▫ Antiseptic/antimicrobial impregnated catheters ▫ Chlorhexidine bathing Central Line Bundle • Critically important … major impact on infection rates ▫ “Bundles that include checklists to prevent central lineassociated bloodstream infections” One of the top 10 “Strongly encouraged patient safety practices” 6 • Incorporated in Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals2, INS 2011 Standards7, and CDC 2011 Guidelines1 • … But not enough! ▫ Does not address care and maintenance practices aimed at reducing intraluminal introduction of microbes A little bit more about “bundles”… • Defined by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI): A small set of evidencebased interventions for a defined patient population and care setting8 • The IHI Central Line Bundle was one of the first 2 bundles developed • Compliance measured as “all or none” – all elements must be delivered unless medically contraindicated Designing a bundle • 3-5 interventions ▫ Already recommended interventions ▫ Accepted in national guidelines and by local consensus of clinicians • Each intervention is relatively independent • Used with a defined patient population in one location • Developed by the multidisciplinary team • Descriptive rather than prescriptive - allows for local customization • Goal of 95% or greater compliance8 Post-insertion care • The term bundle is often used but there is no well established, well-tested post-insertion care bundle yet • More challenging than the central line insertion bundle ▫ Central line bundle mainly focused during time of insertion ▫ Post-insertion care focused during entire dwell time Involves many clinicians and potentially several health care settings Involves every catheter access/care procedure Challenging to monitor care behaviors Data suggest the need to focus attention on post-insertion care • More comprehensive data collection submitted to and analyzed by the NHSN is useful in designing infection prevention programs • Example: ▫ In 2010 it was found that in the state of Pennsylvania, 71.7% of CLABSIs occurred more than five days after insertion, suggesting internal lumen contamination and the need to pay more attention to catheter maintenance procedures 9 Another example: Poor compliance with dressing changes • N=420 CVADs evaluated in a single hospital10 • N=130 (31%) of CVAD dressings suboptimal and needed changing (e.g. blood under dressing, exposed insertion site, visible moisture) • No correlation with BSI ▫ Researchers believe infections complex and require multi-modal preventative programs ▫ Efforts must address CVAD maintenance – beyond the central line insertion bundle Dressings and Risk for Infection • Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial 1636 patients (ICU) in initial trial; 1419 with at least one dressing change included in analysis11 • 11,036 dressing changes, 67% unplanned due to soiling/undressing • More than 2 dressing changes for disruption were associated with a greater than threefold increase in risk of infection/BSI • Risk factors for dressing disruption included femoral/jugular sites • Post-insertion bundles are insufficiently implemented/ study reinforces need Some potential components of a postinsertion care bundle aimed at infection prevention • • • • • The main Hand hygiene focus of today’s Regular site care presentation Dressing changes IV administration set changes Accessing the needleless connector for catheter flushing/medication/solution administration • Maintaining catheter patency Needleless Connectors (NC)12 • Many different NC products -- categorized into: ▫ Simple: No internal mechanisms; fluid flows straight through the internal lumen. Includes those with a split septum ▫ Complex: Characterized by an internal mechanism that controls the flow of fluid through the device, allowing both infusion and aspiration of blood Attention to needleless connectors and catheter hubs • Needleless connectors and stopcocks are known sources of contamination1 • Disinfection of the NC is recognized as a critical prevention strategy1 • Adequacy of disinfection dependent upon antiseptic agent, contact time, method of application (friction and chemical kill critical) ▫ Consistency problems! Accessing the needleless connector • Steps include ▫ Gathering supplies ▫ Performing hand hygiene ▫ Scrubbing/disinfecting NC What solution? How long? Dry time? Prior to each access? ▫ Attaching syringe/IV administration set maintaining sterility of syringe/set tip and no touch contamination of disinfected NC Infusion Nurses Society Standards • “The needleless connector should be consistently and thoroughly disinfected using alcohol, tincture of iodine, or chlorhexidine gluconate/alcohol prior to each access. The optimal technique or disinfection time has not been identified.”7 • NOTE: INS STANDARDS UNDER CURRENT REVISION (2016) • 13 A 5 second scrub with 70% alcohol • Inpatient setting/prospective observational study 13 • Cultures performed on CVADs with NC (split septum type) and no active infusion ▫ Prior to disinfection, and after vigorous scrub with 70% alcohol for 5, 10, 15, 30 seconds ▫ 5 second dry time, cultures by pressing NC onto agar plate • In vitro assessment ▫ Sterile NC inoculated with S. epidermidis and allowed to dry for 3 hours ▫ Vigorous scrub with 70% alcohol for 0, 5, 10, 15, 30 seconds, 5 second dry time and then cultured Results • 363 NCs sampled in clinical phase13 ▫ 58/87 NCs cultured without disinfection showed bacterial contamination ▫ 5 second scrub (n=71) – one (1.4%) yielded microbial growth ▫ Similar results with 10, 15, 30 second scrub times ▫ No significant differences in microbial contamination rates between 5, 10, 15, 30 second disinfection times • In vitro results ▫ 100% of NCs sampled after no disinfection showed heavy microbial growth ▫ When inoculum size was smaller, all NCs had sterile cultures when scrubbed for 5 or more seconds with 70% alcohol ▫ For larger inoculum, minimal growth after 5 second scrub, sterile culture for 10 second or longer scrub • Implications ▫ The 5 second scrub was effective with the type of NC used – cannot be generalized to other types of NCs13 Chlorhexidine-alcohol • Laboratory study 14 • Mechanical NC (one type) inoculated with a variety of bacteria and yeast and dried for 24 hours at room temperature • Scrubbed with 70% alcohol or 3.14% chlorhexidine/70% alcohol for less than one second, 5, 15, 30 seconds and allowed to dry for 30 seconds • With ≥5 second scrub, both performed similarly • Residual disinfectant activity up to 24 hours with chorhexidine/alcohol solution 2014 SHEA/IDSA Guidelines: Disinfecting NCs • Disinfect catheter hubs, needleless connectors, and injection ports before accessing the catheter (quality of evidence: II) 15 a. Before accessing catheter hubs, needleless connectors, or injection ports, vigorously apply mechanical friction with an alcoholic chlorhexidine preparation, 70% alcohol, or povidoneiodine. Alcoholic chlorhexidine may have additional residual activity compared with alcohol for this purpose. b. Apply mechanical friction for no less than 5 seconds to reduce contamination. It is unclear whether this duration of disinfection can be generalized to needleless connectors not tested in these studies. c. Monitor compliance with hub/connector/port disinfection since approximately half of such catheter components are colonized under conditions of standard practice. Alternative Solutions • Consideration for special products as an alternative to “scrubbing” the needleless connector ▫ Protective alcohol caps for needleless connectors (and the male luer end of IV administration sets) Emerging research documenting effectiveness “Special approach” -- SHEA/IDSA Guidelines 201415 ▫ Scrub products that require minimal scrubbing time 2014 SHEA/IDSA Guidelines: Alcohol Disinfection Caps • Use an antiseptic-containing hub/connector cap/port protector to cover connectors (Grade I) ▫ Recommended as a “special approach” i.e. recommended in locations/populations with unacceptably high CLABSI rates despite implementation of basic practice recommendations 15 One of the studies supporting alcohol disinfection caps … • Use of an alcohol disinfection cap placed on the needleless connector significantly reduced line contamination, density of organisms, and CLABSIs16 • 3 phases: ▫ phase 1 baseline – standard scrub of needleless connector, ▫ phase 2 – disinfection cap placed on all CVADs ▫ phase 3 – back to standard scrub. • Contamination and organism density were measured via an aspirate from the PICC. When no one is looking, do you and your colleagues ALWAYS scrub the hub? Most nurses KNOW that the needleless connector must be scrubbed before each access but what affects our decision to do it? “Missed Nursing Care: Errors of Omission” • Sample of 459 nurses in 3 hospitals completed a survey – “Missed Nursing Care Survey” 17 • Assessment (overall) reported to be missed by 44% of respondents ▫ IV site care and assessment according to hospital policy missed 62% of the time ▫ Hand hygiene missed 30% of the time • Reasons: labor resources, material resources, communication • Conclusions: Patients being placed in jeopardy; critical problem which calls for strategies/interventions “Intention” to Disinfect the NC • Cross-sectional study 18 • N = 171 nurses from 4 Magnet hospitals • Survey: ▫ Demographic data ▫ Autonomy and self-efficacy scales ▫ “Smith-Becker Attitudes towards Disinfection Techniques” scale “Intention” to Disinfect the NC • Findings and some implications 18 ▫ There was a strong relationship between concern for preventing bacterial migration into bloodstream and propensity to use best practice Teaching should focus not only on knowledge and skills but also address the affective domain of learning (caring, patient advocacy) ▫ Experienced nurses have greater autonomy and self-efficacy ▫ But recent graduates were more likely to disinfect every time ▫ Tenured staff – do they avail themselves of educational opportunities that newer graduates have received? ▫ Easy intervention: ready access to supplies “ensure adequate supply of alcohol swabs at bedside” Challenges of Implementing Evidence-based practices 19,20 • Lack of time • Lack of autonomy to change practice • Too much reliance on education and transmission of information as a change strategy Policies versus Adherence • Snapshot look at US Hospitals enrolled in the National Health & Safety Network (NHSN) 21 • 975 hospitals provided data on presence of policies in 1,534 ICU units • In relation to CLABSI prevention, widespread presence of policies (87-97%) • However, adherence to such policies ranged from 37-71% SHEA/IDSA Implementation Strategies15 • A helpful framework ▫ Engage Involve organization champions ▫ Educate Address knowledge, critical thinking, behavior , psychomotor skills, attitudes, beliefs Documented competency ▫ Execute Standardize care processes – implement guidelines, bundles, protocols ▫ Evaluate Link process and outcome data to competency assessments Surveillance Example: Post-Insertion Care Bundle Success Outside of the ICU • Six hospitals, 3-phase study over 4.5 years 22 • Development of a maintenance bundle: ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ Hand hygiene Aseptic technique during NC use (10-15 sec. scrub) CVAD dressing changes Frequency of NC, IV tubing, dressing changes Assessment of CVAD need • Some issues identified ▫ Policies did not address NC disinfection ▫ Nurse survey: < 20% reported using 10-15 sec. scrub • Phases of study: ▫ 1: Pre-intervention, introduction of CVC maintenance bundle after 6 months of CLABSI surveillance; online teaching module ▫ 2: Collaborative team expanded – nursing leadership, MDs etc. ▫ 3: Post-intervention – repeat nurse survey Data collection: 3-4 audits/unit per month (250 of direct observations; 800 dressing integrity observations); also documentation reviews • Outcomes: ▫ Nurse survey – increase from 20-70% report of NC disinfection; during audits 82% compliance with this aspect of bundle; 90% compliance with other bundle elements ▫ CLABSI: 2.6 to 2.1 to 1.3 per 1000 line days (pre-intervention, during intervention, postintervention) 22 Some conclusions: • “standardized education and the hard wiring of processes into the daily work flow were key to developing a self-sustaining CLABSI prevention program” • Attribute success to ▫ Education to improve nursing knowledge ▫ Engagement and increased awareness of burden of CLABSI ▫ Multidisciplinary review of each affected patient – making infection “more relevant” to staff ▫ Interventions in conjunction with audits and feedback22 Another example: • Quality improvement data; seven years of zero bloodstream infections in PICCs placed by the PICC team. 23 • An innovative catheter bundle that addresses not only the central line insertion bundle but also a focus on post-insertion care and maintenance by a dedicated vascular access team and attention to RN education • Interventions included in the care bundle included: ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ 100% use of ultrasound guidance during placement maximal barrier precautions chlorhexidine skin preparation use of a chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing catheter stabilization neutral needleless connector a standard flushing protocol daily line monitoring. Summary/Conclusions • Disinfection of NC should be one component of a postinsertion bundle ▫ Established guideline for scrub duration still lacking ▫ Adherence difficult to monitor Staff teaching techniques to foster patient advocacy important • Scrubbing with 70% alcohol most prevalent ▫ Easy & cost-effective • Scrubbing with chlorhexidine/alcohol ▫ Implemented by some organizations ▫ Acceptable disinfectant per INS 2011, CDC 2011, SHEA/IDSA 2014 ▫ More expensive • Alcohol disinfection caps ▫ ▫ ▫ ▫ Studies showing efficacy Saves time Less dependent on “human factors” More expensive – issue especially for home care, long-term care settings “True nursing ignores infection, except to prevent it” Florence Nightingale, Notes on Nursing Questions, Comments, and Discussion References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. O’Grady et al (2011) Healthcare Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter related infections, Am J Infect Control, 39 (4 supp): S1-S34. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hicpac/pdf/guidelines/bsi-guidelines-2011.pdf The Joint Commission (2014) National patient safety goals. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/standards_information/npsgs.aspx Vital signs: Central line-associated bloodstream infections – United States, 2001, 2008, and 2009. MMWR 60 (8), p. 246. Shang et al. (2014) The prevalence of infections and patient risk factors in home health care: A systematic review. AJIC 42, 479-484. Rinke, M.L. et al. (2013) Bringing central line-associated bloodstream infection prevention home: CLABSI definitions and prevention policies in home health agencies. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety 39 (8), 361-370. Agency for Healthcare Policy and Research (AHRQ) (2013) Making Health Care Safer II: An Updated Critical Analysis of the Evidence for Patient Safety Practices – Executive report. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/evidence-based-reports/ptsafetysum.html Infusion Nurses Society (INS). (2011). Infusion Nursing Standards of Practice. Journal of Intravenous Nursing, 34(1S), S1–S110. Resar R et al. (2012) Using Care Bundles to Improve Health Care Quality. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Retrieved from: http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/UsingCareBundles.aspx. Davis, J. (2011) Central-line-associated bloodstream infection: Comprehensive, data-driven prevention. Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority 8 (3). Retrieved from http://patientsafetyauthority.org/ADVISORIES/AdvisoryLibrary/2011/sep8(3)/Pages/100.aspx Rupp, ME et al. (2013) Hospital-wide assessment of compliance with central venous catheter dressing recommendations. American Journal of Infection Control 41, 89-91. Timsit, JF et al. (2012) Dressing disruption is a major risk factor for catheter-related infections. Critical Care Medicine 40 (6), 1707-1714. Hadaway, L & Richardson, D (2010) Needleless connectors: A primer on terminology. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 33 (1), 22-31. Rupp, ME et al. (2012) Adequate disinfection of a split-septum needleless intravascular connector with a 5-second alcohol scrub. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 33 (7), 661-665. Hong, J. et al. (2013) Disinfection of needleless connectors with chlorhexidine-alcohol provides long-lasting residual disinfectant activity. American Journal of Infection Control 41, e77-e79. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA)/ Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA): Strategies to prevent central-line associated bloodstream infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/676533 Wright, M. O. et al. (2013) Continuous passive disinfection of catheter hubs prevents contamination and bloodstream infection. American Journal of Infection Control, 41, 33-38. Kalisch, BJ et al. (2009) Missed nursing care: errors of omission. Nursing Outlook 57 (1), 3-9. Smith, JS et al. (2011) Autonomy and self-efficacy as influencing factors in nurses’ behavioral intention to disinfect needleless intravenous systems. JIN 34 (3), 193-200. Solomons, NM, Spross, JA (2011) Evidence-based practice barriers and facilitators from a continuous quality improvement perspective: an integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management 19, 109-120. Weingart, SN (2014) Implementing practice guidelines: easier said than done. Israel Journal of Health Policy Research 3 (20). Stone et al (2014) State of infection prevention in US hospitals enrolled in the National Health and Safety Network. AJIC 42, 94-9. Dumyati, G, Concannon, C, van Wijngaarden, E et al (2014). Sustained reduction of central line-associated bloodstream infections outside the intensive care unit with a multi-modal intervention focusing on line maintenance. AJIC 42, 723-730. Harnage, S (2012) Seven years of zero central-line associated bloodstream infections. British Journal of Nursing 21 (21), S6, S8, S10-S12.

© Copyright 2026