T his PDF was auto- generated on 2014- 11- 11... .

T his PDF was auto- generated on 2014- 11- 11 18:51:48 +0100. A more recent version of this page may

be available at http://osdoc.cogsci.nl/tutorials/capybara/.

Cats, dogs, and capybaras

T his OpenSesame workshop was presented at the Center for Mind/ Brain Sciences

at the University of Trento on May 7th. T his page is a slightly modified version of

the original workshop page, which can be found here.

Overview

About

Step 1: Download and start OpenSesame

Step 2: Making your experiment Android-ready

Step 3: Add a block_loop and trial_sequence

Step 4: Import images and sound files

Step 5: Define the experimental variables in the block_loop

Step 6: Add items to the trial sequence

Step 7: Define the central fixation dot

Step 8: Define the animal sound

Step 9: Define the animal picture

Step 10: Define the touch response

Step 11: Define the correct response

Step 12: Define the logger

Step 13: Add per-trial feedback

Step 14: Add instructions and goodbye screens

Step 15: Finished!

Extra (easy): A smarter way to define the correct response

Extra (medium): Add breaks and per-block feedback

Extra (difficult): Limit the presentation duration

References

About

We will create a simple animal-filled multisensory integration task, in which

participants see a picture of a dog, cat, or capybara. In addition, a meowing or

barking sound is played. To make things more fun, we will design the experiment so

that you can run it on an Android device, using the OpenSesame runtime for Android.

You will see that this requires hardly any additional effort.

T he participant’s task is to report whether a dog or a cat is shown, by tapping (or

clicking) on the left (dog) or right (cat) side of the screen. No response should be

given when a capybara is shown (i.e. those are catch trials). T he prediction is simple:

Participants should be faster to identify dogs when a barking sound is played, and

faster to identify cats when a meowing sound is played. In other words, we expect a

multisensory congruency effect. A secondary prediction is that when participants

see a capybara, they are more likely to report seeing a dog when they hear a bark,

and more likely to report seeing a cat when they hear a meow.

Figure 1. Don't be fooled by meowing capybaras! ( Source)

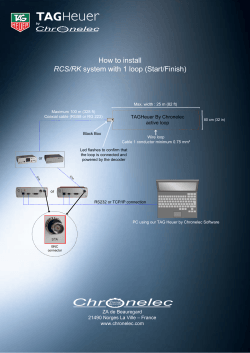

Step 1: Download and start OpenSesame

OpenSesame is available for Windows, Linux, Mac OS (experimental), and Android

(runtime only). T his tutorial is written for OpenSesame 2.8.1 or later. You can

download OpenSesame from here:

http://osdoc.cogsci.nl/

When you start OpenSesame, you will be given a choice of template experiments,

and a list of recently opened experiments (if any, see %FigStartup).

Figure 2. The OpenSesame window on start-up.

T he ‘Droid template’ provides a good starting point for creating Android-based

experiments. However, in this tutorial we will create the entire experiment from

scratch. T herefore, we will continue with the ‘default template’, which is already

loaded when OpenSesame is launched (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The structure of the 'Default template' as seen in the overview area.

Background box 1

Let’s introduce the basics: OpenS esame experiments are collections of items . An item is

a small chunk of functionality that, for example, can be used to present visual stimuli

(the sketchpad item) or record key presses (the keyboard_response item). Items have a

type and a name. For example, you might have two keyboard_response items, which are

called t1_response and t2_response. To make the distinction between the type and the

name of an item clear, we will use code_style for types, and italic_style for names.

To give structure to your experiment, two types of items are especially important: the

loop and the sequence. Understanding how you can combine loops and sequences to build

experiments is perhaps the trickiest part of working with OpenS esame, so let’s get that

out of the way first.

A loop is where, in most cases, you define your independent variables. In a loop you can

create a table in which each column corresponds to a variable, and each row

corresponds to a single run of the ‘item to run’. To make this more concrete, let’s

consider the following block_loop (unrelated to this tutorial):

Figure 4. An example of variables defined in a loop table. (This example is not related to the

experiment created in this tutorial.)

T his block_loop will execute trial_sequence four times. Once while soa is 100 and target is

‘F’, once while soa is 100 and target is ‘H’, etc. T he order in which the rows are walked

through is random by default, but can also be set to sequential in the top- right of the

tab.

A sequence consists of a series of items that are executed one after another. A

prototypical sequence is the trial_sequence, which corresponds to a single trial. For

example, a basic trial_sequence might consist of a sketchpad, to present a stimulus, a

keyboard_response, to collect a response, and a logger, to write the trial information to

the log file.

Figure 5. An example of a sequence item used as a trial sequence. (This example is not related to

the experiment created in this tutorial.)

You can combine loops and sequences in a hierarchical way, to create trial blocks, and

practice and experimental phases. For example, the trial_sequence is called by the

block_loop. Together, these correspond to a single block of trials. One level up, the

block_sequence is called by the practice_loop. Together, these correspond to the practice

phase of the experiment.

Step 2: Making your experiment Android-ready

Click on ‘New experiment’ in the overview area to open a tab that has some general

options for the experiment. To make our experiment work on Android devices, we

need to select the droid back-end in the ‘back-end’ pull-down menu.

Change the resolution to 1280 x 800 px. You don’t have to worry about the actual

resolution of the phone/ tablet that you will run the experiment on, because the

display will be scaled automatically. But 1280 x 800 px is the resolution that you will

develop with.

T hat’s it. You have now made the necessary changes to run your experiment on

Android!

Background box 2

T he back-end is the layer of software that controls the display, input devices, sound, etc.

Many experiments will work with all back- ends, but there are reasons to prefer one

back- end over the other, mostly related to timing and cross- platform support. For more

information about back- ends, see:

/back- ends/about

Step 3: Add a block_loop and trial_sequence

T he default template starts with three items: A notepad called getting_started , a

sketchpad called welcome , and a sequence called experiment . We don’t need

getting_started and welcome , so let’s remove these right away. To do so, right-click

on these items and select ‘Delete’. Don’t remove experiment , because it is the entry

for the experiment (i.e. the first item that is called when the experiment is started).

Our experiment will have a very simple structure. At the top of the hierarchy is a

loop, which we will call block_loop. T he block_loop is the place where we will define

our independent variables (see also Background box 1). To add a loop to your

experiment, drag the loop icon from the item toolbar onto the experiment item in

the overview area.

Because a loop item always needs another item to run, a dialog will appear that asks

whether you want to create a new item for the loop or whether you want to select

an existing item. We want to create a new sequence for our loop, so select sequence

in the pull-down menu labeled ‘Create new item to use’ and click on the ‘Create’

button.

By default, items have names such as sequence , loop, _sequence , etc. T hese names

are not very informative, and it is good practice to rename them. Item names must

consist of alphanumeric characters and/ or underscores. To rename an item, rightclick on the item in the overview area and select ‘Rename’. Rename sequence to

trial_sequence to indicate that it will correspond to a single trial. Rename loop to

block_loop to indicate that will correspond to a block of trials.

T he overview area of our experiment now looks as in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The overview area at the end of Step 3.

Background box 3

T ip – Deleted items are still available in the ‘Unused items’ bin, until you select

‘Permanently delete unused items’ in the ‘Unused items’ tab. You can re- add deleted

items to a sequence using the ‘Append existing item’ button.

Step 4: Import images and sound files

For this experiment, we will use images of cats, dogs, and capybaras. We will also

use sound samples of meows and barks. You can download all the required files

from here:

/attachments/cats-dogs-capybaras/stimuli.zip

Download stimuli.zip and extract it somewhere (to your desktop, for example).

Next, in OpenSesame, click on the ‘Show file pool’ button in the main toolbar (or:

Menu →View → Show file pool). T his will show the file pool, by default on the right

side of the window. T he easiest way to add the stimuli to the file pool is by dragging

them from the desktop (or wherever you have extracted the files to) into the file

pool. Alternatively, you can click on the ‘+’ button in the file pool and add files using

the file-selection dialog that appears. T he file pool will automatically be saved with

your experiment if you save your experiment in the .opensesame.tar.gz format

(which is the default format).

After you have added all stimuli, your file pool looks as in Figure 7.

Figure 7. The file pool at the end of Step 4.

Step 5: Define the experimental variables in the block_loop

Conceptually, our experiment has a fully crossed 3x2 design: We have three types of

visual stimuli (cats, dogs, and capybaras) which occur in combination with two types

of auditory stimuli (meows and barks). However, we have five exemplars for each

stimulus type: five meow sounds, five capybara pictures, etc. From a technical point

of view, it therefore makes sense to treat our experiment as a 5x5x3x2 design, in

which picture number and sound number are factors with five levels.

OpenSesame is very good at generating full-factorial designs. First, open block_loop

by clicking on it in the overview area. Next, click on the ‘Variable wizard’ button. T he

variable wizard is a tool for generating full-factorial designs. It works in a

straightforward way: Every column corresponds to an experimental variable (i.e. a

factor). T he first row is the name of the variable, the rows below contain all possible

values (i.e. levels). In our case, we can specify our 5x5x3x2 design as shown in Figure

8.

Figure 8. The loop wizard generates full-factorial designs.

After clicking ‘Ok’, you will see that there is a loop table with four rows, one for

each experimental variable. T here are 150 cycles (=5x5x3x2), which means that we

have 150 unique trials. Your loop table now looks as in Figure 9.

Figure 9. The loop table at the end of Step 5.

Step 6: Add items to the trial sequence

Open trial_sequence . You will see that the sequence is empty. It’s time to add some

items! Our basic trial_sequence is:

1.

2.

3.

4.

A

A

A

A

sketchpad to display a central fixation dot for 500 ms.

sampler to play an animal sound.

sketchpad to display an animal picture.

touch_response to collect a response.

5. A logger to write the data to file.

To add these items, simply drag them one by one from the item toolbar onto the

trial_sequence . If necessary, you can open trial_sequence and re-order it by dragging

the newly added items by their grab-handle (i.e. the four-square icon on the left).

Once all items are in the correct order, give each of them a sensible name. T he

overview area now looks as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. The overview area at the end of Step 6.

Step 7: Define the central fixation dot

Click on fixation_dot in the overview area. T his will open a basic drawing board that

you can use to design your stimulus displays. To draw a central fixation dot, first

click on the fixation-dot icon (with the small gray circle) and then click on the center

of the display, i.e. at position (0, 0).

We also need to specify for how long the fixation dot is visible. To do so, change the

duration from ‘keypress’ to 495 ms, in order to specify a 500 ms duration. (See

Background box 4 for an explanation.)

T he fixation_dot item now looks as in Figure 11.

Figure 11. The fixation_dot item at the end of Step 7.

Background box 4

Why specify a duration of 495 if we want a duration of 500 ms? T he reason for this is

that the actual display- presentation duration is always rounded up to a value that is

compatible with your monitor’s refresh rate. T his may sound complicated, but for most

purposes the following rules of thumb are sufficient:

1. Choose a duration that is possible given your monitor’s refresh rate. For example, if

your monitor’s refresh rate is 60 Hz, it means that every frame lasts 16.7 ms (=1000

ms/60 Hz). T herefore, on a 60 Hz monitor, you should always select a duration that is

a multiple of 16.7 ms, such as 16.7, 33.3, 50, 100, etc.

2. In the duration field of the sketchpad specify a duration that is a few milliseconds

shorter than what you’re aiming for. S o if you want to present a sketchpad for 50 ms,

choose a duration of 45. If you want to present a sketchpad for 1000 ms, choose a

duration of 995. Etcetera.

For a detailed discussion of experimental timing, see:

/miscellaneous/timing

Step 8: Define the animal sound

Open animal_sound . You will see that the sampler item provides a number of

options, the most important one of which is the sound file that is to be played. Click

on the browse button to open the file-pool selection dialog, and select one of the

sound files, such as bark1.ogg.

Of course, we don’t want to play the same sound over-and-over again. Instead, we

want to select a sound based on the variables sound and sound_nr that we have

defined in the block_loop (Step 5). To do this, simply replace the part of the string

that you want to have depend on a variable by the name of that variable between

square brackets. More specifically, ‘bark1.ogg’ becomes ‘[sound][sound_nr].ogg’,

because we want to replace ‘bark’ by the value of the variable sound and ‘1’ by the

value of sound_nr.

We also need to change the duration of the sampler. By default, the duration is

‘sound’, which means that the experiment will pause while the sound is playing.

Change the duration to 0. T his does not mean that the sound will be played for only

0 ms, but that the experiment will advance right away to the next item, while the

sound continues to play in the background. T he item animal_sound now looks as

shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. The item animal_sound at the end of Step 8.

Background box 5

For more information about using variables, see:

/usage/variables- and- conditional- statements/

Step 9: Define the animal picture

Open animal_picture . T his will again open a sketchpad drawing board. Now select the

image tool by clicking on the button with the aquarium-like icon. Click on the center

of the screen (0, 0). T he ‘Select file from pool’ dialog will appear. Select the file

capybara1.png and click on ‘Select’. T he capybara will now lazily stare at you from

the center of the screen. But of course, we don’t always want to show the same

capybara. Instead, we want to have the image depend on the variables animal and

pic_nr that we have defined in the block_loop (Step 5).

We can use the basic same trick as we did for animal_sound , although things work

slightly differently for images. First, right-click on the capybara and select ‘Edit’.

T his will allow you to edit the following line of OpenSesame script that corresponds

to the capybara picture:

draw image 0.0 0.0 "capybara1.png" scale=1.0 center=1 show_if="always"

Now change the name of image file from ‘capybara.png’ to ‘[animal][pic_nr].png’ …

draw image 0 0 "[animal][pic_nr].png" scale=1 center=1 show_if="always"

… and click on ‘Ok’ to apply the change. T he capybara is now gone, and

OpenSesame tells you that one object is not shown, because it is defined using

variables. Don’t worry, it will be shown during the experiment!

To remind the participant of the task, we will also add two response circles, one

marked ‘dog’ on the left side of the screen, and one marked ‘cat’ on the right side.

I’m sure you will able to figure out how to do this with the sketchpad drawing tools.

My version is shown in Figure 13. Note that these response circles are purely visual,

and we still need to explicitly define the response criteria (see Step 10).

Finally, set ‘Duration’ field to ‘0’. T his does not mean that the picture is presented

for only 0 ms, but that the experiment will advance to the next item (the

touch_response ) right away. Since the touch_response waits for a response, but

doesn’t change what’s on the screen, the target will remain visible until a response

has been given.

Figure 13. The animal_picture sketchpad at the end of Step 9.

Background box 6

T ip – OpenS esame can handle a wide variety of image formats. However, some (nonstandard) .bmp formats are known to cause trouble. If you find that a .bmp image is not

shown, you may want to consider using a different format, such as .png. You can convert

images easily with free tools such as GIMP.

Step 10: Define the touch response

Open the touch_response item. T he touch_response collects a tap (for devices with a

touch screen) or a mouse click (for devices with a mouse) and automatically recodes

the response coordinates into discrete response values based on a grid. T his may

sound a bit abstract, but it simply means the following. T he display is divided into a

grid and each cell in the grid gets a number. T he value of the response is the number

of the cell that is tapped/ clicked. For example, if you divide the display into four

columns and three rows and the participant taps the cell labeled ‘7’, then the

response variable will have the value ‘7’ (see Figure 14).

Figure 14. The touch_response item records display taps and mouse clicks and assigns a response

value based on a grid.

In our case, we simply divide the screen into a left and a right side, which means that

we have to set the number of columns to 2 and the number of rows to 1 (it is by

default). Following the logic shown in Figure 14, the left side of the display now

corresponds to a 1 response, and the right side corresponds to a 2 response. (Note

that we are therefore much more liberal than the visual response circles of Figure 13

suggest, because we accept taps/ clicks anywhere on the screen.)

Finally, we have to make it possible for participants not to respond, because the

response should be withheld on capybara trials. To do so, we change the ‘T imeout’

field from ‘infinite’ to ‘2000’. T his means that the response will automatically time

out after 2000 ms. When this happens, the response will be set to ‘None’ and the

experiment will continue.

T he touch_response now looks as in Figure 15.

Figure 15. The touch_response at the end of Step 10.

Step 11: Define the correct response

So far, we haven’t defined what the correct response is for each stimulus. T ypically,

this is done by defining a correct_response variable in the loop table. Response

items, such as the touch_response will automatically use this variable to decide

whether a response was correct or not, unless a different correct response is

explicitly provided in the item.

Open the block_loop. Click on ‘Add variable’ and add a variable named

‘correct_response’. T his will add a long empty column to the table. On rows where

animal is ‘dog’, set correct_response to 1 (i.e. left-side tap). Where animal is ‘cat’, set

correct_response to 2 (i.e. right-side tap). Where animal is ‘capybara’ set

correct_response to ‘None’ (i.e. a timeout). I recommend using some clever copypasting to save some time!

Step 12: Define the logger

Actually, we don’t need to configure the logger, but let’s take a look at it anyway.

Click on logger in the overview to open it. You will see that the option ‘Automatically

detect and log all variables’ is selected. T his means that OpenSesame logs

everything, which is fine.

Background box 8

T he one tip to rule them all – Always triple- check whether all the necessary variables

are logged in your experiment! T he best way to check this is to run the experiment and

investigate the resulting log files.

Step 13: Add per-trial feedback

It is good practice to inform the participant of whether the response was correct or

not. To avoid disrupting the flow of the experiment, this type of immediate

feedback should be as unobtrusive as possible. Here, we will do this by briefly

showing a green fixation dot after a correct response, and a red fixation dot after an

incorrect response.

First, add two new sketchpads to the end of the trial_sequence . Rename the first one

to feedback_correct and the second one to feedback_incorrect . Of course, we want to

select only one of these items on any given trial, depending on whether or not the

response was correct. To do this, we can make use of the built-in variable correct,

which has the value 0 after an incorrect response, and 1 after a correct response.

(Provided that we have defined correct_response, which we did in Step 11.) To tell

the trial_sequence that the feedback_correct item should be called only when the

response is correct, we use the following run-if statement:

[correct] = 1

T he square brackets around correct indicate that this is the name of a variable, and

not simply the string ‘correct’. Analogously, we use the following run-if statement

for the feedback_incorrect item:

[correct] = 0

We still need to give content to the feedback_correct and feedback_incorrect items.

To do this, simply open the items and draw a green or red fixation dot in the center.

Also, don’t forget to change the durations from ‘keypress’ to some brief interval,

such as 195.

T he trial_sequence now looks as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 16. The trial_sequence at the end of Step 13.

Background box 9

For more information about conditional ‘if’ statements, see:

/usage/variables- and- conditional- statements/

Step 14: Add instructions and goodbye screens

A good experiment always start with an instruction screen, and ends by thanking the

participant for his or her time. T he easiest way to do this in OpenSesame is with

form_text_display items.

Drag two form_text_displays into the main experiment sequence. One should be at

the very start, and renamed to form_instructions . T he other should be at the very

end, and renamed to form_finished . Now simply add some appropriate text to these

forms, for example as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17. The form_instructions item at the end of Step 15.

Background box 10

T ip – Forms, and text more generally, support a subset of HT ML tags to allow for text

formatting (i.e. colors, boldface, etc.). T his is described here:

/usage/text/

Step 15: Finished!

Your experiment is now finished! Click on the ‘Run fullscreen’ ( Control+R) button in

the main toolbar to give it a test run. If you have an Android device, you can transfer

the experiment file to the device (typically to the SD card), launch the OpenSesame

runtime for Android, and select the experiment file to launch it.

Background box 11

T ip – A test run is executed even faster by clicking the orange ‘Run in window’ button,

which doesn’t ask you how to save the logfile (and should therefore only be used for

testing purposes).

Extra (easy): A smarter way to define the correct response

In Step 11, we have defined correct_response variable manually. T his works, but it

takes time and is prone to mistakes. A smarter way is to use an inline_script and a

bit of deductive logic to determine the correct response for a given trial. First, open

block_loop and remove the correct_response column, because we don’t need it

anymore. Next, drag an inline_script item from the item toolbar to the start of the

trial_sequence . Open the prepare tab of the inline_script and add the following

script:

if self.get('animal') == 'dog':

exp.set('correct_response', 1)

elif self.get('animal') == 'cat':

exp.set('correct_response', 2)

else:

exp.set('correct_response', None)

So what’s going on here? First things first: T he reason for putting this code in the

prepare tab is that every item in a sequence is called twice. T he first phase is called

the prepare phase, and is used to perform time consuming tasks before the timecritical run phase of the sequence. Determining the correct response is exactly the

type of preparatory stuff that you would put in the prepare phase. During the run

phase, the actual events happen. To give a concrete example, the contents of a

sketchpad are created during the prepare phase, and during the run phase they are

merely ‘flipped’ to the display. For more information about the prepare-run

strategy, see:

/usage/prepare-run/

T he script itself is almost human-readable language, at least if you know the

following. Firstly, to retrieve an experimental variable in an inline_script, you need

to use self.get(). So where you would write [animal] in OpenSesame script, you

write self.get('animal') in a Python inline_script. Secondly, to define an

experimental variable, you need to use exp.set(). T herefore, to set the variable

correct_response to 2, you call exp.set('correct_response', 2). For more

information, see:

/python/about/

We can summarize the script as follows: If the picture is a dog, the correct response

is 1. But if the picture is a cat, the correct response is 2. If the picture is neither (and

by exclusion must therefore be a capybara), the correct response is no response, or

a timeout (indicated by ‘None’).

Finally, let’s consider the following variation of the script above:

if self.get('animal') == 'dog':

exp.set('correct_response', 1)

elif self.get('animal') == 'cat':

exp.set('correct_response', 2)

elif self.get('animal') == 'capybara':

exp.set('correct_response', None)

else:

raise Exception('%s is not a valid animal!' % self.get('animal'))

Here we allow for the possibility that an animal is neither a dog, nor a cat, nor a

capybara. And if we encounter such an exotic creature, we abort the experiment with

an error message, by raising an Exception. T his may feel like a silly thing to do,

because we have programmed the experiment ourselves, and we (think we) know

with 100% certainty that it includes only cats, dogs, and capybaras. But it is

nevertheless good practice to add these kinds of sanity checks to your experiment,

to protect yourself from typos, logical errors, etc. T he more complex your

experiment becomes, the more important these kinds of checks are. Never assume

that your code is bug-free!

Extra (medium): Add breaks and per-block feedback

Right now, our experiment consists of a single, very long block of trials. In most

experiments, you would keep your block_loop short (30 trials, say) and repeat it

several times with a short break after each block.

However, this approach doesn’t work here, because we have a lot of unique trials

(150 to be exact), and there is no straightforward way to divide these trials into

multiple blocks. T herefore, we will use the following trick: We will add a feedback

item to our trial_sequence , and use a run-if statement to call it only after every 50

trials. T his is moderately advanced, but follow me!

First add a feedback item to the end of the trial_sequence . Next, assign the following

run-if statement to it:

=self.get('count_trial_sequence') % 50 == 49

Note that this run-if statement starts with an = sign. T his means that it is Python

syntax, instead of the simplified OpenSesame script that you used before (e.g.

[correct] = 0 is OpenSesame script). T he use of Python gives us a lot of extra

flexibility. Next, we retrieve the value of the experimental variable

count_trial_sequence. T he count_[item name] variables are built-in variables that

keep track of how often an item has been called, starting from 0. In other words,

count_trial_sequence corresponds to the trial number. Finally, we take the modulo

50 of the trial number and check whether it equals 49. Modulo is a mathematical

operator that returns the remainder of an integer division. For example, 13 % 5

equals 3, because 5 goes twice into 12 and leaves 3.

Why does this work? If we start counting at 0, we want to insert a break after trials

49, 99, and 149. T hese trial numbers have in common that their modulo 50 is 49. T his

is why this run-if statement works. Get it?

We still need to add some content to the feedback item. OpenSesame automatically

keeps track of certain feedback variables, which you can use to inform the

participant of his or her performance. For example, the variable avg_rt contains the

average response time, and acc contains the percentage of accurate response. An

example of a good feedback display is shown in Figure 18.

Figure 18. An example feedback display.

For more information about feedback, see:

/usage/feedback/

Extra (difficult): Limit the presentation duration

Right now, the animal picture stays on the screen until the participant gives a

response. But let’s say that we want to limit the presentation duration of the picture

to 1000 ms. If we want to remove the picture during the response interval, we have

to do things in parallel. And because of the purely serial way in which OpenSesame

works, this is a bit tricky. Let’s take a look at one way to do this, by replacing both

the animal_picture and touch_response items by an `inline_script.

First, remove animal_picture and touch_response from the trial_sequence , and add a

single inline_script in their place. Now add the following code to the prepare phase

of the inline_script (see the code comments for an explanation):

# Import the canvas and mouse classes

from openexp.canvas import canvas

from openexp.mouse import mouse

# Determine the full path to the animal picture in the file pool. This goes

as

# follows. First get the animal and pic_nr variables ...

animal = self.get('animal')

pic_nr = self.get('pic_nr')

# ... use these variables to determine the picture filename (e.g.,

'cat1.png') ...

picture_name = '%s%d.png' % (animal, pic_nr)

# ... and get the full path to the picture in the file pool.

picture_path = exp.get_file(picture_name)

# Now create a canvas and draw the animal picture on it

my_animal_canvas = canvas(exp)

my_animal_canvas.image(picture_path)

# Create a blank canvas

my_blank_canvas = canvas(exp)

# Create a mouse object

my_mouse = mouse(exp)

T he script above creates a canvas with the animal picture, an empty canvas, and a

mouse object. But so far it’s all preparation–T he script doesn’t do anything visible.

Which brings us to the run phase of the inline_script:

# The time that we want to show the animal picture

animal_duration = 1000

# The response timeout, relative to the onset of the animal picture

response_timeout = 3000

# Show the canvas with the animal picture and remember the presentation

# timestamp

target_timestamp = my_animal_canvas.show()

# Collect a mouseclick (= touch on Android) with a timeout specified in

# animal_duration

button, position, response_timestamp = my_mouse.get_click(

timeout=animal_duration)

# If the response time was less than animal_duration, sleep for the

remainder of

# the time to make sure that the animal picture always stays on the screen

for

# the time specified in animal_duration.

if response_timestamp-target_timestamp < animal_duration:

self.sleep(animal_duration-response_timestamp+target_timestamp)

# Show the blank canvas, i.e. remove the animal picture

my_blank_canvas.show()

# If the previous response collection timed out (i.e. button == None), then

we

# need to poll for a mouse click again.

if button == None:

button, position, response_timestamp = my_mouse.get_click(

timeout=response_timeout-animal_duration)

# If both the first and the second attempt to get a mouseclick timed out,

we

# set the response to 'None' ...

if button == None:

response = 'None'

# ... but if we were able to get a response, we determine the coordinates of

the

# click (or touch). If it is on the left side of the screen, we set the

response

# to 1, else we set the response to 2.

else:

x, y = position

if x < self.get('width')/2:

response = 1

else:

response = 2

# Determine the response time and the correctness

response_time = response_timestamp - target_timestamp

if response == self.get('correct_response'):

correct = 1

else:

correct = 0

# Print useful information to the debug window

print('correct = %s' % correct)

print('response = %s' % response)

print('response_time = %s' % response_time)

# And process the response using the semi-automatic `set_response()`

function.

exp.set_response(response, response_time, correct)

If you aren’t very familiar with Python and OpenSesame, the script above may look

overwhelmingly difficult. But the logic is actually quite simple:

1. Present the animal picture

2. Collect a response until the animal picture must be removed (i.e. 1000 ms)

3. If a response was received in step 2, sleep for the remainder of the time that the

animal picture should be visible

4. Remove the animal picture (i.e. present a blank canvas)

5. If a response was not received in step 2, try to collect a response again

T hat’s it. Once you’re able to see understand this logic, and you understand how this

logic can be implemented in an inline_script, you will pretty much be able to

implement every experiment you want!

References

Mathôt, S ., S chreij, D., & T heeuwes, J. (2012). OpenS esame: An open- source, graphical

experiment builder for the social sciences. Behavior Research Methods , 44(2), 314–324.

doi:10.3758/s13428- 011- 0168- 7

Copyright 2010- 2014 S eba stia a n Ma thôt // Downloa d a s .ta r.gz // Revision #3ef937 on T ue Nov 11 17:51:29 2014

© Copyright 2026