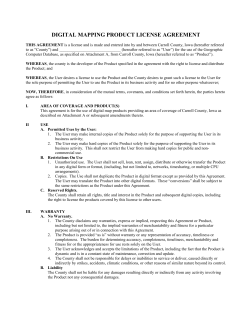

KEY ASPECTS OF IP LICENSE AGREEMENTS Donald M. Cameron Rowena Borenstein