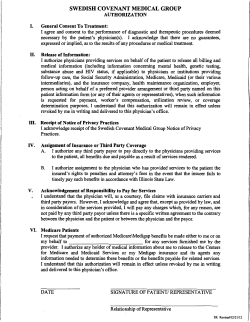

The Physician’s First Employment Contract _______________________