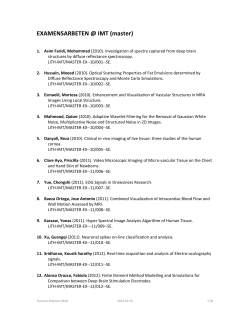

T h e r