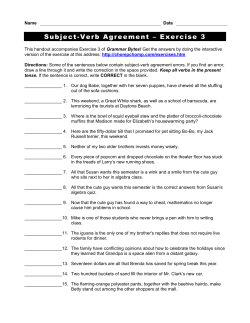

DETECTING ERRORS IN SUBJECT-VERB AGREEMENT DURING ON-LINE SENTENCE COMPREHENSION IN SPANISH _______________