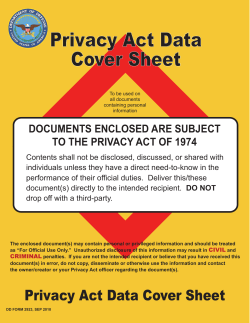

PACITA