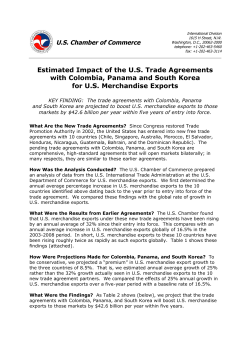

Document 43805