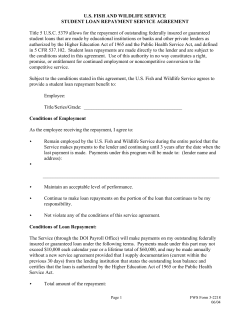

Document 44185