Hyperlink-Spelling (aka orthography) Spoken vs. written language: word form and spelling

Hyperlink-Spelling (aka orthography)

Spoken vs. written language: word form and spelling

Word form

Spelling (orthography)

Principles of writing

Syllabary

Ideograms

Alphabet

Runes, runic alphabet, aka the futhorc

IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet)

English spelling

OE spelling

Caedmon‟s Hymn

Middle English spelling

French influence

Ormulum

Chancery English

Caxton and the advent of printing

EModE spelling

The Great Vowel Shift (GVS)

Standardization of spelling

ModE spelling

Spelling reform; reform movements and reforms

Simplification

Regularization

Derivational uniformity

Reflection of pronunciation

Indication of stress

Pronunciation spellings

Hyphenation

Individual words

The New Spelling

Language planning and policy

Authorities (dictionaries, manuals of usage)

Spellers

Dictionaries

Manuals of usage

Spelling pronunciations

Scottish English

Non-standard spelling

Archaisms

Nonce and advertising spellings

Literary practices

Dialect spellings

Eye dialect

Literary comedians

Texting literature

Informal spellings

Word formation, borrowing, and spelling

Acronyms

Borrowings

Clippings

Hyperlink-Spelling (aka orthography)

Spoken vs. written language

Word form

Spelling (orthography)

(Principles of writing)

(Rules of English spelling)

(Historical practice)

(Present-Day practice)

Spoken vs. written language is a contrast which reflects two aspects of the same phenomenon. The

spoken language is primary in the sense that it is learned before the written language is. Indeed, speakers

of a language can be fluent and creative users of the language without necessarily being literate at all.

Furthermore, numerous languages spoken in today‟s world do not have a writing system. The written

language is, in the sense just mentioned, secondary, but it is not just a reflection of the spoken language

from which is somehow abstracted. It relies on different ways of expressing the distinctions which

speech makes by means of tempo, pitch, intonation, and stress, but it cannot replicate them fully, just

as it cannot reflect the voice quality of the individual speaker. On the other hand, handwriting, too, in

very individual and cannot be copied by speech style or voice quality. Furthermore, the written

language can make use of symbols (e.g. @, , , ), tables, diagrams and other figures – all of which

cannot be reproduced in the spoken language or at least not easily.

The spoken language is more immediate (usually restricted to people close by), generally more short-lived

(bar a recording), more spontaneous, and more individual while the written language is more

independent of the circumstances of its production, accessible over a longer period of time, often

carefully planned and even edited, and subject to conventions of standardization, including spelling in

particular. Written grammar tends to be fussier and more complex than spoken grammar, but also

more generally free of the lexical vagaries like and stuff, fillers such as like or y’know, false starts (well, I, I

… she finally said yes), hesitiation signals (uh), and redundancies (I liked it – it was really good, absolutely tops)

of speech. Perhaps because of these differences many speakers of the language consider the written

language to be the “real” language and miss the point that the two forms of the language fulfill

different functions, each appropriate and legitimate in its own right.

As far as English is concerned, there are probably quite a few speakers of the language besides young

children who are not (functionally) literate. On the other hand, as English spreads across the world as a

global language there are probably very many users of the language who are more comfortable with the

written than the spoken language, esp. since spelling is highly fixed while accent varies enormously.

Word form is the shape of a lexeme on a particular occasion, including an identical sequence of letters or

sounds. Example: Herkneth to me, gode men - Wives, maydnes, and alle men - Of a tale that ich you wile telle

(Text 4.6) has eighteen different word forms; in other words, both occurrences of men count separately

as do me and ich, which are two forms of one single lexeme (the 1st person singular personal pronoun).

A word form is the concrete, physical occurrence of a word and may be graphic or phonetic in nature;

indeed, it may be tactile (e.g. in the braille alphabet) or visually signed in sign language. In contrast, a

lexeme is abstract, which means that the repeated occurrence of the “same” word form can only be

interpreted as the occurrence of same lexeme more than once.

Spelling (orthography) is the conventional means of representing language in the written medium.

English uses the Latin alphabet for this, but once also used runes. The principle of English spelling is

– despite its bad reputation, which itself is due largely to a lack of serious spelling reform – phonetic.

Many of the exceptions are due to borrowing or to sound changes (see also archaisms) which have

occurred since spelling was fixed. Examples: <ea> is regularly used for /i/ as in <beat>, but uneven

change means that quite a few exceptions exist where the pronunciation is /e/, e.g. <death>, and a

few where it is /e/ <great>.

(Spoken vs. written language: word form and spelling)

Principles of writing

Syllabary

Ideograms

Alphabet

Runes

IPA

(Rules of English spelling)

(Historical practice)

(Present-Day practice)

Principles of writing can be realized in a wide variety of ways. Some languages use a syllabary, some use

ideograms or a logogram system of characters, others, like English use an alphabet. There are also

rebus-supported systems of writing.

A syllabary makes use of graphic symbols which stand not for a single sound (or phoneme), but for a

combination of sounds, usually a consonant + vowel combination, which together make up a syllable.

Japanese uses a syllabary, as does Cherokee. Example: the following comes from a chart of the

syllabary used to write the Cherokee language. As you can see, the first line combines an initial /ts/and

the second line an initial /w/ with the vowels in each column: a – e – i – o – u – . All told the

Cherokee syllabary consists of some 85 syllabograms.

Ideograms are characters said to correspond to “ideas” (meanings) rather than to pronunciations.

Chinese is the best known example of a language with a writing system made up of ideograms. The

total number of characters which are available for Chinese may lie close to 50,000 even though

normally well educated users of Chinese can manage very well with between three and four thousand.

Example:

is the character for hànzì “Chinese character.”

English stands in distinct contrast to Chinese inasmuch as it uses a phonetic writing system or alphabet.

English does, of course, use holistic symbols such as <#> or <%> or <$>, and, indeed, it always has

as we see in the use of <7>, a character from the Tironian notes (devised by Marcus Tullius Tiro, 1034 BE), the secretary of Cicero, as a stenographic short-hand ), which stands for ond “and” in much the

way that <&> (ampersand) does today. English sometimes indulges in the fun of a text containing

rebus forms (a rebus is picture or symbol which resembles the intended sound or spelling). Example:

(A poor old man was driving a pig to market with a whip tied to its leg when by some accident the pig

got loose. The man ran after him, but piggy es[caped] …

While the example just given is a bit older, we should not forget that people still love the ludic element

in such texts and play it out in texting or e-mail language.

Alphabet is a system of written symbols which represent sounds. In our case, an alphabet, but which one?

For there are quite a few. Examples:

(Greek); а б в г д е (Cyrillic);

(Hebrew); or a b c

d e (Latin)? OE used runes in the very early period, but OE spelling adopted the Latin alphabet with

the phonetic values of the letters associated with it and added new letters to represent some of the

sounds which differed from Latin. These graphs include thorn <þ>, which is used for present-day

<th>, as is <>, called eth. In Text 2.1 <þ> occurs initially only, as in þis “this” or þā “the/those

(nominative plural)”; and <> elsewhere, e.g. fri “peace, refuge” or oerne “other, second, next.” Both

of them are pronounced either as voiceless// or voiced //depending on their position in a word

and the stress pattern of the word. Wynn <ƿ> for /w/ is a further graph used in OE, but not present

in the Latin alphabet. A final, slightly unusual letter is <æ> as in þær “there, then.” It is called “ash”

and is pronounced as a low front vowel, for which the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) uses

the same symbol /æ/.

Very limited use was made in OE of distinct capital letters. However, the differentiation began to grow as

the Carolingian script spread in the period after the 9th century. The parallel existence of both uncial

(majuscule) script and Carolingian minuscule script led to a capital-lower case distinction (Color plate

no. 2.2 Mercy and Truth [Carolingian minuscule]). ME added the letter yogh <ȝ> for /j/, /g/, and

//. In the long term the Latin alphabet was adopted in its classical form with 23 letters. During the

EModE period printers ceased to use the letters unfamiliar to present-day readers of English even

though <y> sometimes served as a replacement for earlier <þ> (see Text 6.2, where ye stands for both

the and thee).

In EModE <i/j> and <u/v> stood in complementary distribution: Initial <v> was used not only where

ModE has <v> as in vallies but also where it has <u> as in Vranias; medial <u> appears in both

huntresse and loue (see Text 6.4). The letter <j> was still rare at the beginning of the period; instead <i>

was used for both the vowel (him) and the consonant (Iesus). Furthermore, we often find <y> where

ModE has <i>: Text 6.2 has both hys and his.

The present English alphabet of 26 letters was finally established when it added three new distinct

graphemes: <w> replaced wynn and a once truly double <u>; and the two pairs of complementary

allographs <i/j> and <u/v> became as distinct graphemes <i> and <u> for vowels and <j> and

<v> for consonants from the end of the Renaissance on.

Other letters than the familiar twenty-six do, in fact, crop up, but these are either printers ligatures like

<œ> for <oe> as in fœtus and <æ> for <ae> as in mediæval or they are graphs (letter forms)

borrowed along with foreign words. Examples: <ç>, <à>, and <ï>, all from French as in façon, vis-à-vis,

and naïve; <ñ> from Spanish as in señor; or <ö> from German as in föhn.

Runes, runic alphabet, aka the futhorc (from the names of the first six runes, as given in the table

below) make up an alphabet used, among others, by the Germanic peoples mostly for inscriptions.

Some of the letters resemble ones in the Latin alphabet; other may have come from Northern Italian

alphabets. The following table reproduces the futhorc (see also Color plate no. 2.1 Runic Pin):

feoh (f)

ger (j)

ing ()

ur (u)

thorn (þ, th)

eoh (eo)

éel ()

peor (p)

dæg (d)

ós (o)

rad (r)

eolh (x, k)

ac (a)

cen (c/k)

sigel (s)

æsc (æ)

gyfu (, g/j)

Tiw (t)

yr (y)

beorc (b)

ior (ia, io)

wynn (w)

hægl (h)

eh (eoh) (e)

nyd (n)

mann (m)

is (i)

lagu (l)

ear (ea)

Relatively few texts written using the furthorc have been passed on. Text 2.2 is one such example,

taken from the Ruthwell Cross (erected in the 7th century) in Southern Scotland and bearing a excerpt

from the poem “The Dream of the Rood.”

IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) (see following chart found at IPA_chart_2005.png). The IPA

offers an alternative set of symbols used to designate sounds unambiguously. If used broadly each

phoneme in a language is assigned one symbol. Example: the <j> in jet, the <dg> in lodge, and the <g>

in privilege are all /d/. A narrow transcription is more strictly phonemic and distinguishes allophonic

variants such as monophthongal [e] and diphthongal [e] for /e/ as in late.

(Spoken vs. written language: word form and spelling)

(Principles of writing)

Rules of English spelling

Rules of OE spelling

Rules of ModE spelling

(Historical practice)

(Present-Day practice)

English spellings follow a relatively straight-forward set of phonetic principles. The reputation of

English spelling is, however, notoriously bad. This lies in the fact the realization of the principles draws

on a large number of traditional spellings which themselves go back to differing conventions of both

spelling and pronunciation. Above all, English orthography has been relatively resistant toward

spelling reform. Among the important traditions we must count (1) the presumed phonetic quality of

the vowels associated with the letters of the Latin alphabet in OE times; (2) French writing

conventions which were adopted in part in the period after the Norman Conquest; (3) differing

regional spelling traditions based on sometimes clearly differing regional pronunciations of English;

(4) the unhistorical remodeling of spelling to conform to the etymological sources of individual

words; (5) the maintenance of older spellings despite often major changes in the pronunciation, as due,

for example, to the Great Vowel Shift; and, finally, widespread borrowing from other languages along

with the foreign spelling conventions. All of this is coupled with a great inertia in undertaking

reform. There were some modest, but widely accepted changes in the EModE period or shortly after

it. But even the limited reforms generally prevailing in AmE have not been embraced within the BrE

spelling tradition.

OE spelling (2.3.1) did not have the strict convention of spaces between words that we are familiar with.

Although most texts used a modified Latin alphabet, not all did. There were, furthermore, regional

differences in spelling which had in part to do with regional differences in pronunciation, but also with

different scribal traditions. Since by far the largest number of OE texts which we have fall within the

Wessex standard, the latter point is not very prominent. For texts which reveals both sorts of

difference, see Text 2.6 and the discussion of it in 2.5.4 (see also below Caedmon’s Hymn).

The OE spelling of the consonants was much more regular than ModE spellings are. The most

inconsistent was the spelling of the fricative. The graph <þ> did not distinguish between the voiceless

and voiced allophones [] and []. Likewise <f> could be /f/ or /v/ and <s>, /s/ or /z/. This was

not a problem however, since the voiceless fricatives /f, , s/ were restricted to initial or final position

while /v, , z/ were medial. Examples: and forgyf us ūre gyltas, swā swā we forgyfaþ ūrum gyltendum (from

the Lord‟s Prayer, Matthew 6:12 qtd from Carpenter 1891: 52) “And forgive us our debts, as we

forgive our debtors,” where the initial and final <f> in forgyf are both /f/, but the second <f> in

forgyfa is voiced /v/. In contrast, <sc> is always the voiceless fricative //. Example: biscopes

“bishops.” And <cg> is always /d/. Example: ecg “edge.” The letter <c> is somewhat difficult to

interpret. Before the front vowels <i> and <ea> palatalization was generally the case, giving us /t/, as

in ciricean “church”; elsewhere <c> is /k/, as, for example, in cyning “king,” diacones “deacon,” or drincæ

“drinks.” In much the same manner <g> may be /j/ before front vowels, as in dæge “days,” gif “if” or

in the verbal prefix ge-, but // elsewhere, cf. gylde “(re-)pay” and scillinga “shillings” (examples from

Text 2.1). One final ambiguous letter is <h>. At the beginning of a word it has the value of /h/, as in

him “him” (3rd person dative) or hām “home,” but it is /x/, like German <ch> or Spanish <j>, before

a consonant, as in Æelbirht or at the end of a word as in feoh “property” (ModE fee).

The letter-vowels are assumed to have been pronounced much like their “Continental” values, but the use

of macrons – or long marks – over the vowel letters in many editions of OE texts is a purely

convenient modern convention based on the presumed length of the vowel, viz. long <ā, æ, ē, ī, ō, ū,

y> with a macron and the same letters without a macron as short. For two vowel-letters together in

words like feoh or gebiege we assume a diphthongal pronunciation /eo/ and /iy/ (cf. Hogg 1992 or Blake

1996 for details on OE pronunciation).

Blake, N. (1996) A History of the English Language. Houndsmill: Palgrave.

Carpenter, S.H. (1891) “The Sermon on the Mount,” In: An Introduction to the Study of the Anglo-Saxon

Language. Boston: Ginn, 49-55.

Hogg, R.M. (1992) “Phonology and Morphology,” In: R.M. Hogg (ed.) The Cambridge History of the

English Language. vol. I. The Beginnings to 1066. Cambridge: CUP, 67-167.

Caedmon’s Hymn is a late 7th century composition which exists in several different versions. The

manuscript from 737 gives us some idea of Anglian usage, and this can be compared to West Saxon

usage. The choice of words in the two versions below is identical with the exception of l.5, which has

Anglian scop aelda barnum “created, the High Lord, for men”, but West Saxon sceop eorðan bearnum

“created the earth for men.” The major differences are to be found in the vowels. It is widely

recognized that West Saxon underwent a process of diphthongization which does not show up in

northern texts. Vowel qualities also seem to have varied. Some apparent differences are, however,

probably only spelling conventions. Since the two texts come from different regions and from

difference times, the variation may be due to either factor or both. The following table, drawn from

material in the texts, is only a selection of the spelling contrasts (see Text 2.6 and the discussion there;

Blake 1996: 69-73; 115-119).

Early Anglian (Northumbrian, MS of 737)

Early West Saxon (1st half of 10th century)

metudæs maecti

meotodes meahte

end his modgidanc,

and his modgeþanc,

2

The Creator‟s power and His conception,

uerc uuldurfadur,

sue he uundra gihuaes,

weorc wuldorfæder,

swa he wundra gehwæs,

The work of the Father of Glory, as He of every wonder

Anglian

West Saxon

Spellings

metuds

meotodes

<> vs. <e> for [e]; the former: an older (or archaic)

form

maecti

meahte

<c>+C vs. <h>+C for [ç]

modgidanc, -, tha

modgeþanc, eoran, þa

<d/th> vs. < /þ> for [/]

uerc uuldurfadur

weorc wuldorfæder

<u> vs. < w> for [w]

-fadur

-fder

<-ur> vs. <-er> for later <-er>; the former an old

genitive

Excerpt from “Cædmon‟s Hymn”: 2009

Following the early, 7th century literary primacy of Northumbria with Bede and Caedmon, as represented

by the preceding text, the literary and political center moved southward to Mercia in the 8th century.

Evidence of the Mercian tradition is to be found in the Life of St. Chad, which is preserved in a 12th

century manuscript, but employs 9th century spelling. This text suggests a pre-Alfredian interest in

translation and reveals a relatively standardized language (Blake 1996: 76). But clearly Mercian power

and the Mercian literary tradition (see Cynwulf) were destroyed by the Norse incursions.

Consequently, West Saxon was to be the standard language, and its spelling what we are most likely to

meet with.

Blake, N. (1996) A History of the English Language. Houndsmill: Palgrave.

Middle English spelling could no longer rely on the orthographic system introduced in connection with

the standardization of West Saxon. Although the West Saxon scribal tradition continued to be

practiced after the Conquest, the surviving standard was no longer prestigious and gradually grew

outdated by change. A number of conventions began to shift, probably largely due to contact with

French. Although no standard emerged in the early ME period, it is possible to see some more or less

general effects. One of these is that non-Latin letters fell into disuse. Eventually, <y> would be used as

a consonant for /j/ and <> would be fully retired. Examples: <i/j>: geong vs. jonge; and <g>: iff vs.

gif. <þ> and <> were being replaced by <th>: þat vs. that or oer vs. othere. Winn <ƿ> now became

rare; and <u>, <uu>, and <w> are used in its place. Independent of these considerations <k> was

coming to be used for /k/, esp. near a front vowel, where <c> + <e, i> would lead to

misinterpretation as /s/ rather than /k/ <k> with front vowels priketh, seeken. Among the grapheme

combinations OE <hw> for /hw/ was somewhat illogically reversed to <wh>, probably under the

influence of other combinations (see ModE spelling) which used <h> as a diacritic, esp. <th>,

<ch>, and <sh/sch>. In the north and East Anglia <qu, u> and in east Midlands <w-> were also

used for /hw/. By this time <c, sc> had been replaced elsewhere by “French-inspired spellings” <ch,

sch> (ibid.: 130).

An account of changes in the spelling of the vowels is considerably more challenging since there were

significant regional differences in pronunciation. A few examples will have to suffice. OE <y>,

originally rounded front /y()/, had become <e> in the southeast, but rounding was retained in the

southwest where <u>, a French spelling, but also <ui> and <uy> occurred. High back rounded /u/

was frequently spelled <ou> in French fashion, esp. in French borrowings licour, flour. And the raising

of OE ā to // led to the use of <o> or <oo> goon, hoot; and <> began increasingly to alternate with

<e> or <a> frd ~ ferd or sahte ~ shte (Blake 1996: 118).

As was the case in OE, in ME, too, there were regional differences which showed up in spelling.

Northern

Southern

ModE

Sanges sere of selcuth rime,

Mony songes of dyuerse ryme

Many a song of different rime,

Inglis, frankys, and latine,

As englisshe frensshe & latyne

In English, French, and Latin.

to rede and here Ilkon is prest,

To rede & here mony are prest

Each one to read and hear is pressed*

þe thynges þat þam likes best.

Of þinges þat hem likeþ best

The things that please them all the best.

Text 4.8: Parallel excerpts from Cursor Mundi, Northern (Cotton) and Southern (Trinity) versions

Pronunciation (through spelling):

Northern English has /a/ for OE ā, where Southern English has // (sanges-songes; also S: mony)

Northern <s>, probably /s/ for Southern <ssh> // (Inglis-englisshe; frankys-frensshe)

Spelling (with no consequences for pronunciation):

Northern English tends to <i> for Southern <y>, but cf. l. 4 (thynges-þinges

Northern has <th> twice and <þ> twice; Southern has only <þ>

Blake, N. (1996) A History of the English Language. Houndsmill: Palgrave.

French influence on the spelling of English became an important and lasting factor in the ME period.

The most significant influence was on vocabulary, but French also reinforced or initiated structural

innovations and influenced spelling. Examples: <qu> for OE <cu> or <cw> quod, quen; <ch> instead

of OE <c> for /t/ chapel, pynchen; <sch> or <sh> instead of OE <sc> for // frendschipe or shoures; and

the distinction between /f/ and /v/ as well as between /s/ and /z/, which were positional variants of

<f> and <s> in OE, is now made maintained by <f> vs. <v/u> over vs. OE ofer. The new letter <z>

was introduced where OE usage would have made do with <s> as lazar “leper” < Lazarus. Gradually,

<th> replaced <þ> and <>, but then as now no orthographic distinction was made between // and

//. And, finally, the representation of the vowels underwent changes due in part to French.

Examples: <ou> instead of OE <u> for /u/ shoures, oure; <> was to disappear in favor of either

<e> or <a>.

Ormulum (see 4.2.3), written in the second half of the 12th century, is one of the key texts in respect to

spelling in ME. This early northeastern text (the author Orm(in) wrote it in Bourne, Lincolnshire)

reveals the author‟s efforts at using a more standardized form of the written language. Although Orm

does not seem to have had imitators. He took great care to distinguish the three sounds, /, j, d/

otherwise represented by OE <> by using two (or including a special <g> with a flat top, three)

distinct graphemes. Orm distinguished between // using <g> and /j/ or /x/ using <>. Example:

grimme “grim, fierce” vs. iff “if” (Text 4.5: Admonition from the Ormulum, second half of 12th

century).

Especially fascinating is his system of indicating long vowels by letting them be followed by a single

consonant only while short vowels were followed by doubled consonants. Examples: þiss boc iss

nemmnedd Orrmulum forrþi þatt Orrm itt wrohhte. “This book is named Ormulum for Orm created it”

(“Preface to Ormulum, ll. 1-2), where all the vowels are short except those in boc, the <u>‟s of

Orrmulum, and <i> in forrþi; the <e> of wrohhte is presumably short. Short and long vowels, which had

not been orthographically distinguished in OE, were differentiated here: the short ones were followed

by double consonant-letters and the long ones by only one, e.g. l. 5 follc (“folk, people”) // vs. l. 7 god

(“good”) /o/. This indicates that the long-short consonant distinction of OE had presumably been

lost (Blake 1996: 125). Orm also sometimes used single accents to mark long vowels (l. 2 tór “difficult”)

or double ones (l. 7 üt “out”).

Blake, N. (1996) A History of the English Language. Houndsmill: Palgrave.

Chancery English, the language of the government administration in London was available as the basis

for spelling from about 1400 on. The clerks of the Chancery were trained into a system of writing

which was highly standardized. Furthermore, clerks from outside the Chancery were also schooled

there. Since the documents produced in the Chancery had high prestige and were circulated

throughout the kingdom, people everywhere were exposed to this kind of language. Yet absolute

uniformity was not demanded, and the actual process of standardization was slow in developing.

Example: if/yf was normal after 1430, but yif/yef/ef continued to occur after this date (Blake 1996:

176ff). A study of the Paston letters show the spread of standardized spellings. In the period 14691479 the letter written by Edmond Paston for his mother Margaret reveal the move from initial <x->

to initial <sch-> and then soon after to initial <sh-> in the word shal(l) (ibid.: 180). Despite the spread

of spelling standards, a fair amount of variation persisted right up into Shakespearean times and well

beyond (see EModE spelling).

A brief look at two English translations of a short passage from the Bible (Genesis 1: 3) into English show

some of the changes in orthography. The first is a Wycliffe translation (1385; see Color plate no. 5.2

Wycliffe. Gospel of St. John); the second comes from the King James Version (KJV) (1611; the

Shakespearean period, but reflecting conservative usage):

ME: Wycliffe: And God seide, Lit be maad, and lit was maad.

EModE: KJV: And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

(Genesis 1:1-5 from: http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Bible_(Wycliffe)/Genesis#Chapter_1)

The text can be understood by a ModE-speaking readership, but there are quite a number of

unfamiliar looking words. They reflect both differing pronunciations and different conventions of

spelling. In a few cases the syntax is in need of comment (see Text 5.2). Spelling:

seide: interchangeability of <ai> and <ei>

lit: use of <> for [ç]

maad: use of double letter-vowels to indicate a long vowel, here: /a/

In Genesis 2:7 we find the following: “Therfor the Lord God formede man of the sliym of erthe, and brethide in to his

face the brething of lijf; and man was maad in to a lyuynge soule. According to Samuels <ij>, as in lijf is typical of

the Central Midland spelling system (Taavitsainen 2000: 143), which was based on the dialects of

Northamptonshire, Huntingdonshire, and Bedfordshire. This orthography was current before 1430 and

continued to be written till the later 15th century. It was distinct and well-defined, i.e. not like “the

„colourless‟ system, which forms a continuum in which the local elements are muted” (ibid.: 135).

Examples of Central Midland Standard:

Central Midlands

ModE

Central Midlands

ModE

Central Midlands

ModE

sich

such

mych

much

stide

stead

ouun

given

ony

any

si

saw

Plus: ech(e), aftir, it, itt, þoruþ, þorou, eyr(e), eir(e), “air,” bitwix, brenn, bisy, ie, ye “eye,” fier, heed, lyve, moun

(“may” plural), puple, peple, renn, togidere. (ibid..: 137)

Over a longer period of time the Central Midlands type of English was prominent in scientific writing

centered in Oxford, but also – due to Wycliffe‟s importance for it – in the Lollard movement. As such,

Central Midlands written English was definitely a rival standard to Chancery English

Blake, N. (1996) A History of the English Language. Houndsmill: Palgrave.

Taavitsainen, I. (2000) “Scientific Language and Spelling Standardisation 1375-1550” In: L. Wright

(ed.) The Development of Standard English 1300-1800. Cambridge: CUP, 131-154.

Caxton and the advent of printing were perhaps to most significant factors in leading to standardization of

spelling. Printers, the first and best known of whom was William Caxton (c. 1415~1422-1492), could only

profit from standardization of the language in vocabulary, dialectal forms, grammar, but above all

orthography. However, the relatively uniform spelling which emerged in printed works long existed side

by side with the often very idiosyncratic practices which even extremely learned writers such as Samuel

Johnson had (see EModE spelling) in their private correspondence or journals.

Regularization spelling was the first stage in the standardization process. While Elizabethan spelling was still

extremely varied – and tolerant of variety – the Restoration (after 1660) put an end to (most of) the

variation in orthography.

EModE spelling (6.3.1, 6.3.1.1- 2, 6.4.2) culminated in the adoption of standardized spelling and punctuation.

There still was some variation (cf. bere and beare; standard and standerd), but by this time spelling is already

very regular and quite similar to present-day conventions. This does not mean, however, that EModE and

ModE spelling were identical. What is characteristic about orthography in the EModE Period is that it

underwent a high degree of regulation in the hands of the printers. For modern eyes 16th and 17th century

spelling seems strange and irregular at times. On the whole, however, there was a great deal of agreement

coupled with a fair amount of toleration of alternative spellings.

Public spelling was determined by printers, who failed to make the adjustments which would have brought

English orthography more closely into line with the traditional values of the letters in the Latin alphabet.

Quite the contrary, respect for learning and a recognition of the etymologies of numerous words led to

changes which made their spellings more Latin-like, e.g. dette became debt (< Latin debitus), amonest became

admonish (< admonire), vittles became victuals (< victualia) (cf. Blake 1996: 203f). Not only did the older and

the newly introduced spellings often exist side by side, private spelling practices also often contained

archaic and idiosyncratic forms which even such luminaries as Dr. Johnson practiced. Although known

for “fixing” the standard, Johnson deviated considerably from it in his letter-writing orthography. The

spelling used in letter-writing is characterized by points (i-iii) (Osselton 1998b: 40ff):

(i) contractions, e.g. &, wch, ym, licce, punishmt, tho, thro, thot, etc. (from letters of Addison‟s, 1st decade of

18th century); some went back to medieval manuscripts; but the practice continues today (see

13.2.2). Contractions reached their peak in the early 18th century;

(ii) phonetic spellings, e.g. don’t, I’ll, „twill; possibly as markers of style;

(iii)retention of older spellings, e.g. diner for dinner (Johnson); cutt (Pope), esp. the diversity in the

spelling of past tense and past participle forms in {ed}, e.g. saved, sav’d, save’d, sav d; lackd, lackt,

lack’t.

(iv) a further convention no longer practiced is the use of diacritic (macron or cedilla) over a vowel to

represent a following <n> or <m>. This was carried over from manuscript traditions. Example:

<-o> for <-on> as in Skelto for Skelton.

The following text, a short selection from William Lily‟s grammar (posthumous 1523), illustrates early

EModE spelling usage.

In speache be theſe eight partes folowinge: [list of the parts of speech]

Of the Noune.

A Noune is the name of a thinge, that may be ſeene, felte, hearde, or underſtande; As the name of my hande in Latine is

Manus: the name of an houſe is Domus: the name of goodness is Bonitas.

Of Nounes, ſome be Subſtantiues, and ſome be Adiectiues.

EModE used the “long <ſ> in non-final position, a practice which continued well into the 18th century.

There are numerous cases of final silent <e>‟s which are no longer written (noune, thinge). The word

Adiectiues illustrates <i> for <j>, non-initial <u> for <v>, and the capitalization of (important) nouns, a

practice that was common from the mid-17th to the mid-18th century and lingered on, at least in letterwriting, until the end of the 18th (Osselton 1998a: 459). The following passage, one hundred and eighty

years later, is taken from Isaac Newton‟s Opticks.

Exper. 8 ... The Book and Lens being made fast, I noted the Place where the Paper was, when the Letters of the Book,

illuminated by the fullest red Light of the solar Image falling upon it, did cast their Species [“image”] on that Paper most

distinctly … (cf. Text 6.4: Isaac Newton. Opticks, 1704)

The title of his book also illustrates the use of <-icks>, where ModE has <-ics>. Final /-k/ was also

spelled <-ique> in words borrowed from French, cf.

8 July. To Whitehall to chapel, where I got in with ease by going before the Lord Chancellor with Mr Kipps. Here I heared

very good musique, the first time that I remember ever to have heard the organs and singing-men in surplices in my life. (cf.

Text 6.1: Samuel Pepys: Excerpts from his diary, 1660)

ModE retains <-ique> only in a few words to signal final stress as in physíque (as opposed to phýsics). For a

closer look at 17th century spelling see Plimoth Plantation.

Osselton, N.E. (1998a) “Spelling-Book Rules and the Capitalization of Nouns in the Seventeenth and

Eighteenth Centuries,” In: M. Rydén, I. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, and M. Kytö. A Reader in Early

Modern English. Frankfurt: Lang, 447-460.

Osselton, N.E. (1998b) “Informal Spelling Systems in Early Modern English: 1500-1800,” In: M.

Rydén, I. Tieken-Boon van Ostade, and M. Kytö A Reader in Early Modern English. Frankfurt:

Lang, 33-45.

The Great Vowel Shift (GVS) (6.3.1.2) brought significant change to pronunciation. The GVS is a chain

shift involving the long vowels of ME. It is not fully clear just when this shift began though it is

generally assumed to have begun in the ME period (Lass 1999: 72f; Bailey/Maroldt 1977: 31; see 5.3.2).

However, the full extent of the shift is best located in the EModE Period. This may be assumed on the

basis of the mismatch between spelling and pronunciation which came about in the course of the shift.

Continental values for <a> are generally low front vowels while English “long” <a> is a raised and

usually diphthongized vowel: long /e/ or diphthongized /e/ as in bake, make, rake. This conclusion

depends on the existence of a sound-to-spelling relationship that is largely congruent with the

Continental phonetic values of the vowel-letters. English spelling was largely fixed by the early 16th

century and represents the stage of pronunciation reached at or before that time, but this no longer

applied by the end of the EModE Period.

Initially digraphs were introduced to express a more specifically English phoneme. This seems to have

been the case with <ea> for // as in meat /mt/ and was thus distinct from <ee> for /e/ as in meet

/met/. In the course of the GVS the // - /e/ contrast was lost and the new merged class was raised

to /i/, which is the present pronunciation. The earlier distinction is, however, still apparent in the

unpredictability of <ea> as /i/, which is the major pattern, or as /e/, a wide-spread though minor

spelling pattern. Examples: <ea> as /i/: beach, bead, each, feature, plead, read (present tense) teak, etc.;

<ea> as /e/: bread, head, read (past tense and past participle).

Bailey, C.-J. N. and K. Maroldt (1977) “The French Lineage of English” In: J.M. Meisel (ed.) Langues en

contact – Pidgins – Creoles – Language in Contact. Tübingen: Gunter Narr, 21-53.

Lass, R. (1999) “Phonology and Morphology,” In: R. Lass (ed.) The Cambridge History of the English

Language. vol. 3. 1476-1776, Cambridge: CUP, 56-186.

Standardization of spelling (6.4.2) The emergence of modern scientific ways of thinking and of seeing

the world led to the founding of the Royal Society in 1660/1662. Its earliest members, including John

Wilkins, Robert Hooke, Christopher Wren, John Evelyn, and Robert Boyle, promoted all branches of

knowledge, and their curiosity about how the world works extended to language, which showed up

when the Society named a committee of twenty-two including Dryden and Evelyn to make suggestions

for the improvement of English. While an academy was never founded, Evelyn (1620-1706)

formulated an impressive program, comprising “a dictionary, a grammar, a spelling reform, lists of

technical terms and dialect words, translations of ancient and modern writers, and works to be

published by members themselves to serve as models for good writing” (Söderlind 1998: 473). The

intention of the Royal Society was fully within the current of thought in the EModE period and on

into the ModE era. Spelling was regulated fairly early on, but vocabulary and grammar were still felt to

be in need of regulation on into the 18th century.

ModE spelling

General

Non-standard spelling

ModE spelling (8.2.6) is only gradually different from that of the EModE period. Among the uniformly

accepted changes we find the move to use lower case letters for all but proper nouns, adjectives, and

verbs (e.g. <Britain, Welsh, Anglicize>). The “long” <ſ>, as in <ſpeech>, disappeared as did the <k>

at the ends of words like <physick>. These are some of the more immediately noticeable changes. A

thorough review of the regularities of ModE sound-to-spelling conventions cannot be made here, but

some general remarks are called for. The consonants of English, in most accents 24 in number, must

be represented by 21 graphs. Unfortunately, use of the letters is not optimal. For example, <c> may

represent both /k/ (cat, cot) and /s/ (ceder, cider) and <g> may stand for both // (gone, gun) and /d/

(gin, gene). This “wastes” the distinctive function of <k>, which is clearly reserved for /k/ and of /j/,

which is used for /d/. Furthermore, <q>, which occurs exclusively before <u> in native words is completely

redundant for /k/. Indeed, the combination <qu> was an innovation taken from French after the Conquest,

when it eventually displaced OE <cw> as in cwic „”quick.” The use of digraphs (two graphs in a fixed

combination) is one way of expanding potential of the alphabet. The most commonly used graph in

English digraphs is <h>, as in <sh> for // (shin), <th> for // (initially in lexical words such as thin)

and // (initially in grammatical words like then), and <c> for /d/ (chin). The combination <ch> is

not quite so simple: In native words it represents /d/ as just illustrated (also: cherry, church, bench). In

words borrowed from Greek <ch> stands for /k/. Examples: character, trachea. More recent borrowing

from French with <ch> are pronounced as //. Examples: chandelier, Chicago. Other digraphs with

<h>: Some accents such as ScE regularly distinguish <wh> for /hw/ (where) as opposed to <w> for

/w/ (wear). <gh> is a relic of /x/ or /ç/ (once pronounced in right, but now lost except in a few

traditional dialects, esp. in Scotland); it is also used in borrowed words to differentiate hard // (Italian

ghetto) from soft /d/ (gentle). Greek borrowings contain <ph> for /f/ (photo) and <rh> /r/ (rhotic), but

neither is really necessary for any purpose other than signaling the Greek source of the words.

Sometimes <kh> is used in transliterations of Russian /x/ (Khrushchev, but pronounced as /k/ in

English), and of <zh> for Russian // (Zhukov). Other combinations with <h> include <bh> (/b/in

Hindi bhang) and <dh> (/d/in Hindi dhoti or Arabic dhow). Historically justified spelling such as <kn->

for /kn/. Example: ME knyght /kniçt/ retains the initial <kn-> in ModE, where it distinguishes now

homophonous (identical in sound) knight from night in spelling only.

The vowels of English are much more complex. Here a repertoire of 16 (GenAm) to 20 (RP) vowels have

to be represented by a mere six vowel-letters (<a, e, i, o, u, y>). The solutions which have evolved

include (1) using digraphs such as <ea, oi, ie, ue> and many others and (2) indicating length or

diphthongization with a following single consonant + a vowel letter as opposed to shortness by a

following single consonant and nothing or a double consonant. The first of these strategies has the

distinct disadvantage of involving a large number of exceptions. Examples:

the major pattern

<ea>

/i/

as in

breathe, lead (verb), appease, ease, release, etc.

the minor pattern

<ea>

/e/

as in

breath, bread, lead (noun), dead, death, etc.

incidental cases

<ea>

//

as in

earth, earn, learn, search

<ea>

/e/

as in

great, steak

Table: Spelling-to-sound variation: the digraph <ea>

The second of the two strategies is more systematic, but still involves numerous exceptions as the

following tables reveal. All the tables revolve around the pronunciation associated with the individual

occurrence of the simple graphemes <a, e, i/y, o, u>. Note that C stands for any consonant-letter; V

for any vowel-letter; and

for no following sound in the same word.

Spelling

Pronunciation

Examples

Some exceptions

<a> + C + V

//

rate, rating

have, garage

<e> + C + V

/i/

mete, scheming, extreme

allege, metal

<i/y> + C + V

/a/

ripe, rhyme, divine

machine, river,divinity1

joke, joking, verbose

come, lose, gone,verbosity1

cute, renewal

-

<o> + C + V

<u> + C + V

1

RP //; GenAm /o/

/(j)u/

Words which end in <-ity>, <-ic>, <-ion> (divinity, mimic, collision) have a short vowel realization of <a, e, i, o, u>

as a result of historical processes (cf. Venezky 1970: 108f).

Table a: The “long” vowels, spelling and pronunciation

Spelling

Pronunciation

Examples

1

Some exceptions

<a> + C + C/

//

rat, rattle

mamma

<e> + C + C/

/e/

set, settler,

-

<i/y>

/ /

rip, ripping, system

-

RP

//

comma

gross

GenAm

//

//

cut, cutter

butte

//2

bush, put, butcher

+ C + C/

<o> + C + C/

<u> + C + C/

1

In RP and RP-like BrE numerous words follow a special rule for <a>, which is frequently pronounced as / /

when followed by <f, s, th> (after, ask, bath) <m, n> plus C (sample, dance), or <lf> (calf, half).

2

“Short” <u> continued to be pronounced as // if it occurred next to a “labial,” that is a consonant produce with

lip-rounding, viz. /b, p, , t/. All the same, there are a few exceptions such as putt /pt/ or bus /bs/. See FOOTSTRUT split.

Table b: The “short” vowels, spelling and pronunciation

Tables c-d give the rules for vowel + <r> in three different graphological contexts:

Spelling

RP

GenAm

Examples

Some exceptions

<ar> + V + (V/ )

/e(r)/

/er/

ware, wary, warier

are, aria, safari

<er> + V + (V/ )

/(r)/

/r/

here, cereal

very

<ir /yr> + V + (V/ )

/a(r)/

/ar/

fire, inquiry, tyre

-

<or> + V + (V/ )

/(r)/

/r/

lore, glorious

-

<ur> + V + (V/ )

/r/

/r/

bureau, spurious

bury, burial

Table c: Vowels before <r> + one letter-vowel and zero or two letter-vowels (cf. Venezky 1970: chap. 7)

Spelling

RP and GenAm

Examples

Some exceptions

<ar(r)> + VC

//

arid, marriage

catarrh, harem

<er(r)>

/e/

peril, errand

err

<ir(r) / yr(r)>

/ /

empiric, irrigate, lyric

GenAm squirrel

<or(r)>

RP //; GenAm //

foreign, oriole, borrow

worry, horrid

<ur(r)>

//

burr, purring

urine

//

RP hurry, turret

Table d: Vowels before <r> or <rr> + letter-vowel + consonant (cf. Venezky 1970: chap. 7)

Spelling

Examples

Some exceptions

//

par, part

scarce

<er>

//

her, herb

concerto, sergeant

<ir / yr>

//

for, bird, Byrd

-

<or>

//

for, fort

attorney

<ur>

//

cur, curd

-

<ar> +

RP and GenAm

/C

Table e:Vowels before <r> + zero or <r> + consonant (cf. Venezky 1970: chap. 7)

Venezky, R.L. (1970) The Structure of English Orthography. The Hague: Mouton.

Spelling reform has been called for over and over despite the widespread acceptance of an essentially

unified norm in orthography. Yet, we should not forget that standard English spelling – be it British or

American – continues to give general preference to etymological spellings, which help to increase interlinguistic intelligibility, and it retains “silent” letters such as the <r> in words like <car> or <card>

thus allowing a more universal acceptance of spelling, in this case between rhotic and non-rhotic

accents.

The usual basis for reform suggestions emphasizes a different principle, viz. to come as close as possible

to a one-to-one relationship between each phoneme of the language and the letter or combination of

letters employed to represent it. In other words, with the exception of a few shorthand systems of

writing such as Pitman shorthand, the alphabetic principle has been maintained. And in most cases the

Latin alphabet has been used, but again there have been exceptions such as Lodwick‟s universal

alphabet (Abercrombie 1972: 51; see also 8.2.6).

Attempts at reform include any one of numerous projects to bring spelling into a closer relation to

pronunciation. Some modest changes have been successful, but the abstractness of the present system

and distance from actual pronunciation allows it to more easily represent many accents. Standard

English spelling – be it British or American – continues to give general preference to etymological

spellings, which help to increase inter-linguistic intelligibility, and it retains “silent” letters such as the

<r> in words like <car> or <card> thus allowing a more universal acceptance of spelling, in this case

between rhotic and non-rhotic accents.

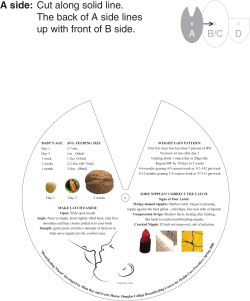

Spelling reforms are not merely haphazard and unsystematic. The reforms initiated by Noah Webster in

the United States are the one aspect of the standard language which he is especially closely associated

with. He ardently supported his changes, which he understood step by step in his spelling book (which

with sales of over 60,000,000 by the 1960s; Color plate no. 10.4 Webster’s American Spelling

Book). Slowly, he changed the spelling of words from one edition to the next so that they became

“Americanized.” He chose s over c in words like defense, he changed the -re to -er in words like center, he

dropped one of the <l>‟s in traveler, and at first he kept the u in words like colour or favour but dropped

it in later editions. He also changed "tongue" to "tung." Much, but not all, of what he proposed was

accepted and is now normal AmE usage. The effects of his major changes can be seen in connection

with the principles of simplification, regularization, derivational unity, reflection of

pronunciation, indication of stress, and pronunciation spellings. As we will see they are not

haphazard, nor are they restricted exclusively to AmE.

Further spelling reforms are not merely haphazard and unsystematic. Instead, we find the principles of

simplification, regularization, derivational uniformity, reflection of pronunciation, including

stress indication, and spelling pronunciations. There are in addition a number of individual,

unsystematic individual differences and nonce spellings, esp. in advertising. Much of the variation

lies in the greater willingness on the part of AmE users to accept the few modest reforms that have

been suggested.

Simplification is a principle common to both the British and the American traditions, but is sometimes

realized differently. It concerns doubling of letters, Latin spellings, and word endings such as in

<catalogue> vs. <catalog>.

Double letters are more radically simplified in AmE, which has program instead of programme, also

measurement words ending in <-gram(me)> such as kilogram(me) etc., where the form with the final <me> is the preferred, but not the exclusive BrE form. Other examples: BrE waggon and AmE wagon;

AmE counselor, woolen, fagot and AmE/BrE counsellor, woollen and faggot. On occasion BrE has the

simplified form as is the case with skilful and wilful for AmE skillful and willful. BrE fulfil, instil, appal may

be interpreted as simplification, but AmE double <-ll-> in fulfill, instill, appall may have to do with

where the stress lies (see indication of stress).

Latin spellings are simplified from <ae> and <oe> to <e> in words taken from Latin and Greek (heresy,

federal etc.) in all varieties of English, but this rule is carried out less completely in BrE, where we find

mediaeval next to medieval, foetus next to fetus and paediatrician next to pediatrician. In contrast, AmE has

simple <e> compared to the non-simplified forms of BrE in words like esophagus / oesophagus; esthetics /

aesthetics (also AmE); maneuver / manoeuvre; anapest / anapaest; estrogen / oestrogen; anemia / anaemia; egis /

aegis (also AmE); ameba / amoeba. Note that some words have only <ae> and <oe> in AmE, e.g. aerial

and Oedipus.

Word endings in AmE may drop of the -ue of -logue in words like catolog, dialog, monolog (but not in words

like Prague, vague, vogue, or rogue). Note also the simplification of words like (BrE) judgement vs. (AmE)

judgment; abridg(e)ment and acknowledg(e)ment.

Simplification vs. derivational uniformity: BrE simplifies <-ection> to <-exion> in connexion, inflexion,

retroflexion etc. AmE uses connection etc. thus following the principle of derivational unity: connect >

connection, connective; reflect > reflection, reflective.

Regularization is evident in AmE, which regularizes <-our> to <-or> and <-re> to <-er> as in honor,

neighbor or in center, theater. This seems justified since there are no systematic criteria for distinguishing

between the two sets in BrE: neighbour and saviour, but donor and professor; honour and valour, but metaphor,

anterior and posterior; savour and flavour, but languor and manor; etc. Within BrE there are special rules to

note: the endings <-ation> and <-ious> usually lead to a form with <-or-> as in coloration and laborious,

but the endings <-al> and <-ful>, as in behavioural and colourful, have no such effect. Even AmE may

keep <-our> in such words as glamour (next to glamor) and Saviour (next to Savior), perhaps because

there is something "better" about these spellings for many people. Words like contour, tour, four, or

amour, where the vowel of the <-our> carries stress, are never simplified.

BrE goitre, centre and metre become AmE goiter, center (but the adjective form is central). BrE has metre "39.37

inches,” but meter “instrument for measuring.” The <-er> rule applies everywhere is AmE except

where the letter preceding the ending is a <c> or a <g>. In these cases <-re> is retained as in acre,

mediocre and ogre in order to prevent misinterpretation as <c> as "soft" /s/ or <g> as /d/. AmE

spellings fire (but note: fiery), wire, tire etc. are used to insure interpretation of these sequences as

monosyllabic. The fairly widespread use of the form theatre in AmE runs parallel to glamour and Saviour,

as mentioned above: it is supposed to suggest superior quality or a more distinguished tradition for

many people.

Derivational uniformity can be from noun

adjective, as in BrE defence, offence, pretence, but AmE defense,

offense, pretense. AmE follows the principle of derivational uniformity: defense > defensive, offense > offensive,

pretense > pretension, practice > practical. (Cf. BrE connexion vs. AmE connection above). Note, however,

AmE analyze and paralyze despite analysis and paralysis.

Reflection of pronunciation. The forms analyze and paralyze, which end in <-ze>, may violate

derivational uniformity, but they do reflect the pronunciation of the final fricative, which is clearly a

lenis or voiced /z/. This principle has been widely adopted in spelling on both sides of the Atlantic for

verbs ending in <-ize> and the corresponding nouns ending in <-ization>. The older spellings with <ise> and <-isation> are also found in both AmE and BrE. AmE Advertise, for example, is far more

common than advertize (also advise, compromise, revise, televise). The decisive factor here seems to be

publishers' style sheets, with increasing preference for <z>. One special case is that of the alternation

between voiceless consonants in nouns (teeth /-/, half /-f/, use /-s/) vs. the corresponding verbs with

a voiced consonant (teethe /-/, halve /-v/, use /-z/). BrE spelling respects this distinction in the pair

practice (n.) vs. practice (v.) despite the lack of a voicing difference. AmE usually spells both with <c>,

which indicates voicelessness.

Indication of Stress determines the doubling or not of final consonants (esp. of <l>) in AmE when an

ending beginning with a vowel (<-ing>, <-ed> follows. If <-er>) is added to a multisyllabic word

ending in <l>, the <l> is doubled if the final syllable of the root carries the stress and is spelled with a

single letter-vowel (<e, o> as opposed to a digraph). If the stress does not lie on the final syllable, the

<l> is not doubled, cf.

re'bel

> re'belling

'revel

> 'reveling

re'pel

> re'pelled

'travel

> 'traveler

com'pel

> com'pelling

'marvel

> 'marveling

con'trol

> con'trolling

'trammel > 'trammeled

pa'trol

> pa'troller

'yodel

> 'yodeled

BrE uniformly follows the principle of regularization and doubles the <l> (revelling, traveler, etc.). AmE

spelling reflects pronunciation (cf. AmE fulfill, distill etc. or AmE installment, skillful and willful, where the

<ll> occurs in the stressed syllable).

Pronunciation spellings are best-known in the case of <-gh->. AmE tends to use a phonetic spelling so

that BrE plough appears as AmE plow and BrE draught ("flow of air, swallow or movement of liquid,

depth of a vessel in water"), as AmE draft. The spellings thru for through and tho' for though are not

uncommon in AmE, but are generally restricted to informal writing (but with official use in the

designation of some limited access expressways as thruways). Spellings such as lite for light, hi for high, or

nite for night are employed in very informal writing and in advertising language. But from there they can

enter more formal use, as is the case lite, which is the recognized spelling in the sense of low-sugar and

low-fat foods and drinks. In other words, an originally advertisement-driven spelling (<light>

<lite>) has gained independent status in its new spelling guise.

Hyphenation varies in the way it is used in the spelling of compounds – be it as two words, as a

hyphenated word, or as a single unhyphenated word varies. In general, AmE avoids hyphenation, cf.

BrE writes make-up ("cosmetics") and AmE make up and BrE neo-colonialism, but AmE neocolonialism. No

hard and fast rules exist, however; and usage varies considerably, even from dictionary to dictionary

within both AmE and BrE.

Individual words have different spellings without there being any further consequences. The following

list includes a few of the most common differences in spelling, always with the BrE form listed first:

aluminium / aluminum

(bank) cheque / check

gaol (also jail) / jail

jewellery / jewelry

(street) kerb / curb

pyjamas / pajamas

storey (of a building) / story

sulphur / sulfur

tyre / tire

whisky / whiskey

Finally, it should be noted that AmE usage is not completely consistent; for example, we find

<advertisement> with <s> and many people write <Saviour> (a reference to Jesus, with a capital)

with <u> and <theatre> with <-re> as if the BrE spelling lent the word more standing. Much of the

variation in AmE lies in the greater willingness on the part of its users to accept the few modest

reforms that have been suggested. Canadians seem to be of two minds about this with the

consequence that we find far more variation – Canadians may, in fact, see the variation as Canadian.

The New Spelling of the Simplified Spelling Society of Great Britain uses the Latin alphabet, which has,

however, been modified to insure greater consistency. It is illustrated in the following rendering of the

beginning of Lincoln “Gettysburg Address” (Text 8.4):

But in a larjer sens, we kanot dedikaet – we kanot konsekraet – we kanot haloe – dhis ground. Dhe braev men, living

and ded, huu strugld heer, hav konsekraeted it far abuv our puur pouer to ad or detrakt.

(MacCarthy 1972: 71)

Conventional spelling:

But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave

men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.

Text: Lincoln‟s Gettysburg Address (excerpt) in the New Spelling

What has been undertaken in the example is the use of <k> only for /k/: kanot, konsekraet, detrakt. /d/ is

always <j> as in larjer. // remains <th> (not shown), but // is spelled as <dh>, as in dhis “this”;

final silent <e> is dropped as in sens. The <e> is sufficient to render /e/ and is consequently also used

in <ded> for standard <dead>. In konsekraet the use of <ae> for /e/ insures the proper vowel

quality, as do <ee> for /i/,<uu> for /u/, or <ou> for /a/. In other words the basic phonetic

principle of English orthography is extended.

Language planning and policy (7.2) Throughout the history of English both the geographic spread of

its speakers and the role of the government or other powerful institutions on the shaping and the

status of the language has become evident again and again. Before its extension beyond England and

the Scottish Lowlands, the use of the language as an everyday medium of communication depended

very much on the settlement patterns of the Saxons. With the introduction of literacy and learning,

centers of cultural power and prestige began to develop, and they tended to exert relatively great

influence on language attitudes among the more educated. In principle, the founding of monasteries

and the program of translation into and writing in English initiated by King Alfred is an early,

important example of language policy in regard to English, one which effectively established the West

Saxon variety and system of spelling as the OE written standard (cf. 3.4-5). In addition, this move

effectively distanced it from Old Norse, which was restricted almost exclusively in the spoken medium.

In the ME period the central question was Which language? Over a period of several hundred years

French and Latin proved to be insufficiently anchored to serve as the daily spoken language. As fewer

and fewer among the powerful nobility could use French with ease, the move to English was a sure

fact. The adoption of English as a written language was a more difficult process since English had little

or no association with the traditions of learning or state authority and administration. A number of

important legal decisions opened English to wider governmental use, for example, the Provisions of

Oxford (1258), which was the first proclamation after the Norman Conquest to be issued not only in

French and Latin but in English as well, and it was the only proclamation in English under Henry III

(see 4.1.2). The translation of the Bible into English was a second major indication of a change in the

status of the language (see 5.2.1.2). The adoption of English for use in the governmental chancery

together with the introduction of printing in England opened the gates, and English became a wellestablished and ever more standardized medium. The fact that there never was a language academy like

the Académie française in France or the Italian Accademici della Crusca was of little import: the weight of

public opinion and the direction of public usage of the language was already well established and the

authorities of language arbitration were clear.

Authorities (dictionaries, manuals of usage) need not be state institutions or language academies. In

effect the printers and publishers working in a largely competitive market – but regionally concentrated

in London – set the standards for the written language. In the end the educational systems of the

various English-speaking countries had little choice but to accept what has de facto become StE. The

instruments of dissemination were the masses of books, pamphlets, broadsides, and newpapers which

employed the new standard spelling (and vocabulary and grammar). For those who were uncertain, the

publishers produced spelling books, dictionaries, and manuals of usage .

Spellers were highly influential and several of them were economically extremely successful. Webster‟s

American Spelling Book, originally titled The First Part of the Grammatical Institute of the English Language. is

one of the best known of these. It went through 385 editions while Webster was still living, and the

income from it supported him well. Yet he constantly endeavored to make improvements in it. The

actual title was changed first to The American Spelling Book (1786) and then to The Elementary Spelling Book

(1829). Most popularly it was called the "Blue-Backed Speller" (see Color plate no. 10.4) because of

its appearance. The main task of Webster's speller was to clarify how words were to be sounded out

and spelled. The idea of reforming and Americanizing English spelling was very much a subsidiary

goal. The Speller was arranged to provide an orderly presentation of words and the rules of their

spelling and pronunciation.

Dictionaries are resources for retrieving information about vocabulary such as spelling, pronunciation,

etymology, style, and meaning. Printed dictionaries are most commonly organized alphabetically.

Because of the numerous exceptions in English spelling, English-users depend far more on dictionaries

than do users of languages with more consistent spelling systems. Especially notable is Samuel

Johnson‟s Dictionary of the English Language (1755; Color plate no. 8.1 Johnson’ Dictionary), which

stands at the beginning of a long tradition of lexicography that would include the incomparable twelvevolume historical Oxford English Dictionary (1928; plus supplements; now in an internet edition) as well

as hundreds and hundreds of further general and specialized dictionaries.

Manuals of usage are resources which set standards for formal written English. They include

information about vocabulary, spelling and punctuation, style, and meaning. Example: The King’s

English by H.W. and F.G. Fowler originally published in 1906.

Spelling pronunciations show the relative prestige and influence of spelling on speech habits. A spelling

like <often> for a word traditionally pronounced /fn/ (GenAm) or /fn/ (RP) is frequently heard

with a medial /t/, a pronunciation which originally went out of fashion in the 16th century. A second

example is <forehead>, which frequently takes on a pronunciation reflecting the two morphemes out

of which it is composed: {fore} + {head} thus ceasing to be /frId/ (RP) or /frId/ (GenAm) and

becoming /fhed/ (RP) or /frhed/ (GenAm). Of this tendency Potter writes: “Of all the influences

affecting present-day English that of spelling upon sounds is probably the hardest to resist” (1976: 77).

There are, in other words, tendencies for people to write the way they speak, but also to speak the way

they write. Nevertheless, the present system of English spelling has certain advantages:

Paradoxically, one of the advantages of our illogical spelling is that...it provides a fixed standard for spelling

throughout the English-speaking world and, once learnt, we encounter none of the difficulties in reading

which we encounter in understanding strange accents. (Stringer 1973: 27)

A further advantage (vis-à-vis the spelling reform propagated so often) is that etymologically related

words often resemble each despite the differences in their vowel quality changes. For example, sonar

and sonic are both spelled with <o> even though the first is pronounced with // or /o/ and the

latter with // or //. The same applies to <c>, which represents both /s/ in historicity and /k/ in

historic.

Potter, S. (1976) Our Language. rev. ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Stringer, D. (1973) Language Variation and English. Bletchley: The Open University.

Scottish English (5.4.3; 5.5.2; 6.5; 8.2.6) long had its own literary and writing traditions. Among the

earliest Scots literature is John Barbour‟s Brus, which was introduced in 5.4.3, but also the heroic

narrative Wallace by Blin Hary (see 5.5.2). Together with the translation the text is readable (see

following) since the grammar is quite similar to that of GenE. The spelling and vocabulary may,

however, cause difficulties.

BUKE FYRST

First Book

OUR antecessowris, that we suld of reide,

Our ancestors, who we should speak of,

And hald in mynde thar nobille worthi deid,

And hold in mind their noble worthy death,

We lat ourslide, throw werray sleuthfulnes;

We let pass by, through veritable slothfulness;

And castis ws euir til vthir besynes.

And continually occupy ourselves with other business.

Till honour ennymys is our haile entent,

To honor our enemies is our whole intention,

It has beyne seyne in thir tymys bywent;

It has been seen in bygone times;

Our ald ennemys cummyn of Saxonys blud,

Our old enemies came of Saxon blood,

That neuyr yeit to Scotland wald do gud,

Who never yet to Scotland would do good,

Bot euir on fors, and contrar haile thair will,

But necessarily and against their will,

Quhow gret kyndnes thar has beyne kyth thaim till.

How great kindness there has been revealed to them.

It is weyle knawyne on mony diuerss syde,

It is well known on diverse sides,

How thai haff wrocht in to thair mychty pryde,

How they have tried in their mighty pride,

To hald Scotlande at wndyr euirmar.

To hold Scotland down evermore.

Bot God abuff has maid thar mycht to par:

But god above has lessened their might:

Text 5.10: Wallace Blin Hary, c.1478

A second selection is from the preface to King James‟ book on writing poetry, which appeared a century

later (1584). The text uses the Scottish spelling <quh> for Southern <wh>; initial /j/ appears as <z>

as in ze “ye.” {-ed} appears as <-it>, reflecting Scottish pronunciation. Many of the vowel realizations

are obviously Northern, quha, knawledge, ane (without initial /w/), sa, baith, sindry, and twa, where

Southern forms would have a back vowel. We find sould with <s-> not <sh->. The inflection <-is>

occurs where StE has <-(e)s>.

The cause why (docile Reader) I have not dedicat this short treatise to any particular personis, (as commounly

workis usis to be) is, that I esteme all thais quha hes already some beginning of knawledge, with ane earnest desyre

to atteyne to farther, alyke meit for the reading of this worke, or any uther, quhilk may help thame to the atteining

to thair foirsaid desyre. Bot as to this work, quhilk is intitulit, The Reulis and cautelis to be observit & eschewit in

Scottis Poesie, ze may marvell paraventure, quhairfore I sould have writtin in that mater, sen sa mony learnet men,

baith of auld and of late hes already written thairof in dyvers and sindry languages: I answer, That nochtwithstanding,

I have lykewayis writtin of it, for twa caussis: ...

(Rhodes et al. (eds.) 2003)

Text 6.9: King James VI. Reulis and Cautelis (1584)

The traditions and conventions of Scots spelling are largely those of StE spelling, but are extended to

a number of specifically Scottish conventions such as <ui> for fronted /jy/; <ae> for /e/. The

spelling is more or less connected to a word‟s phonemic realization but leaves leeway for varying

regional realizations as with <ui> in guid, which can be /gd/ (Angus), /gwid/ (Northeast), /ged/

(Fife), /gyd/(Glasgow), or /gid/ (Black Isle) (McClure 1980: 30).

The Scots Leid Associe (kent in Inglis as the Scots Language Society) is a bodie that warks for the furdal o the

Scots leid in "leiterature, drama, the media, education an ilka day uiss." It wis foundit in 1972, an haes about 350

memmers the nou.

The SLA sets furth a bi-annual journal, 'Lallans, that's nou a 144-page magazine wi prose, musardrie, reviews, news

etc. aw in Scots. It's furthset wi help by the Scottish Arts Council. Lallans is postit free tae memmers o the SLA, an it

is estimate that it haes a readership o about a thousan, syne copies is also postit tae libraries an siclike.

As weil as thon, the SLA hauds its "Annual Collogue" - a meetin wi writin competeitions for fowk o aw ages, talks,

muisic etc. This last aw day, for ordinar.

(http://sco.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scots_Leid_Associe)

Text 8.5: Suggested spelling for Scots

(General)

Non-standard spelling

Dialect spellings

Literary practices

Eye dialect

Non-standard spelling has been in retreat as a result of the normative pressure of schooling, especially

after the advent of universal education, chiefly from the 19th century on. Standard English spelling may

be associated with a wide variety of accents. Consequently, non-standard spelling shows up largely

where writers are less trained in the standard. Examples of non-standard spelling can be found in

advertising, in literature aiming to be comical, at dialect literature, and in informal writing such as

texting.

While much of this is concerned with more recent developments, we should not overlook the fact that

non-standard spelling has a long tradition. In earlier times the lack of a standard in informal writing has

allowed us to make conclusions about regional pronunciations. Excerpts from Henry Machin‟s diary of

the mid-16th century (Text 6.8) is one such example. Here we see both <Westmynster> and

<Vestmynster>, which suggests that the /w/ - /v/ contrast was not fully stable in London English at

this time. The spelling <harme> instead of <arm>, on the other hand, seems to be a case of

hypercorrection in spelling indicating, for one, an awareness that aitch-dropping was often considered

to be an error and, for another, that it must have been fairly widespread in the London of the times. A

second-grade (seven year old) American child who writes a postcard home from summer camp and

mentions buying a <boddel> of paint indicates by means of his or her non-standard spelling that the

<t> of bottle is flapped and voiced.

Nonce and advertising spellings (13.3.1.1; 13.3.1.3). While non-standard spelling on the part of the

poorly educated is unconscious, purposely irregular, non-standard, and nonce spellings are employed in

advertising and in dialect spelling. In the case of nonce (< (for) then anes “for the once”→ the nonce)

spellings the new “word” is intended only “for the moment.” Examples: <E-Z> (“easy,” which works

only for AmE, where the letter <z> is zee and not zed) or <Xtra>.

Quite obviously, advertising, which is very concerned about catching eyes, is highly likely to use such

“nonce” spellings. In this case the motivation for non-standard spelling lies in the attention which this

may potentially generate for the product advertised. It has, for example, reinforced the use of the letter

<k> as in the Kwik-E-Mart fictional chain of convenience stores on The Simpsons, where it is possible to

buy Krusty-Os cereal – all a take-off on some of the commercial uses of misspelling. This lies behind

such well known brand names as <Krispy Kreme> (a kind of doughnut or rather do-nut), <Kleenex>

(facial tissue), or <Weetabix> (a breakfast cereal).

Comical spelling is a further area in which alternatives to the standard orthographic system show up.

Like much else discussed here, the tradition of “misspelling” is not of recent origin. Its beginnings lie

close to the tradition of misspelling that was so popular in 19th century America (Text 13.5). The

following excerpt is an example of this and uses eye dialect to indicate the socially marginal or illeducated status of dialect speakers.

Almost every boddy that knows the forrest, understands parfectly well that Davy Crockett never loses powder

and ball, havin' ben brort up to blieve it a sin to throw away amminition, and that is the bennefit of a vartuous

eddikation. I war out in the forrest won arternoon, and had jist got to a plaice called the grate gap, when I seed a

rakkoon setting all alone upon a tree. I klapped the breech of Brown Betty to my sholder, and war jist a going to put

a piece of led between his sholders, when he lifted one paw, and sez he, "Is your name Crockett?"

Sez I, "You are rite for wonst, my name is Davy Crockett."

(Botkin 1944: 25)

Text: Davy Crockett

Eye dialect is spelling which suggests non-standard language because it violates spelling conventions thus

intimating that the speaker to whom the eye dialect is attributed is illiterate, socially low-standing, or

humorous. It is dialect for the eye not the ear, for when pronounced a word is no different than the

“same” word in standard spelling. Example: W’at for what (Text 10.5). The following text illustrates eye

dialect as well as spelling intended to indicate dialect pronunciation via non-standard spelling. It is

taken from one of the many dialect stories written by Joel Chandler Harris, a white Southern journalist,

in the late 19th century (Color plate no. 10.5 Harris’ Uncle Remus). This particular selection uses