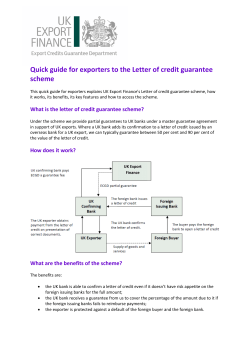

WTO NEGOTIATIONS ON THE AGREEMENT ON ANTI-DUMPING PRACTICES Technical Paper June 2005