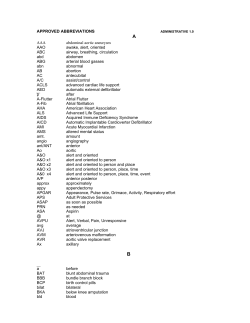

N C V