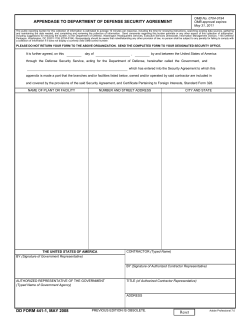

F C D O