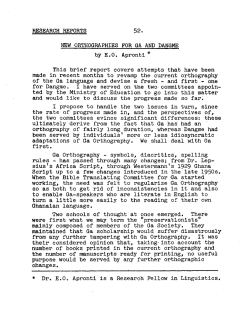

Orthographic Awareness and Metacognitive Management thereof. Including Marginalised Aspects of Literacy Instruction:

Including Marginalised Aspects of Literacy Instruction: Orthographic Awareness and Metacognitive Management thereof. Dr Susan Galletly B.Sp.Thy, Grad Dip Teach, M.Ed., PhD CQUniversity & Education Queensland Email: [email protected] Include & Impact 2011 LSTAQ/LDA/SPELD Conference Brisbane 16-17 September 2011 Please read our theorising on Orthographic Advantage Theory and Transition-from-Early-to-Sophisticated Literacy Do discuss it with your peers: It’s either rubbish, or possibly this century’s biggest paradigm shift ! Galletly, S. A., & Knight, B. A. (2004). The high cost of orthographic disadvantage. Australian Journal of Learning Disabilities, 9, 4-11. Galletly, S. A., & Knight, B. A. (2011). Transition from Early to Sophisticated Literacy (TESL) as a factor in cross-national achievement differences. Australian Educational Researcher. Galletly, S. A., & Knight, B. A. (In press b). Because trucks aren‟t bicycles: Orthographic complexity as an important variable in reading research. Australian Educational Researcher. Galletly, S. A., & Knight, B. A. (2011). A theory of differential disadvantage of Anglophone weak readers with language and cognitive processing weakness. Australasian Journal of Special Education. PART 1: THE THEORY Q: Do we need to leverage literacy development? A: YES! What’s the evidence? 100% Lev5 80% Lev4 60% Lev3 40% Lev2 20% Lev1 Germany Taiwan Switzerland Belgium Estonia Poland Sweden Netherlands Australia Liechtenstein NZ Ireland Canada Hong Kong Finland 0% Korea % of cohort at each level Schools & Ed associations calling for higher literacy resourcing to reduce proportions of lower achievers. Internationally we do well, but still >> low achievers, e.g., compare Australia with Korea &Finland in PISA 2006 <Lev1 Q: What’s Orthographic Awareness? A: Awareness/use of spelling patterns: Spelling, Orthographic Awareness & Reading Accuracy relate reciprocally to boost each other. Key instructional implication: Build them together in a co-ordinated manner! Orthographic Awareness (Knowledge & Skills) Q: What’s Orthographic Advantage Theory? Step 1. Dream a little! Imagine if… Every child had parents who read well & love reading. All children had proficient reading accuracy & spelling in 4 to 18mths, i.e. Most by End-Yr1? No students above Grade 2 had reading accuracy or spelling difficulties: • Even students with intellectual challenge. Q: What’s Orthographic Advantage Theory? Step 1. Dream a little! What if… Every child had parents who read well & love reading. Step 2. Stop dreaming! That’s reality in All children had proficient transparent reading accuracy & spelling in 4 to 18mths, i.e. Most by orthography nations. End-Yr1? No students above Grade 2 had reading accuracy or spelling difficulties: • Even students with intellectual challenge. This creates the reality of massive differences in resourcing needs between Anglophone and transparent orthography nations. It can be easy to learn to read & write all words? How quickly could you learn to read & write using my ‘Fleksispel’: A 44 rule English orthography Wuns upon u tiem thair wer three litul pigz hou livd in a smorl hows with thair muthu. Wun dae muthu pig sed tou her noysee childrun, “It’s tiem for you tou bild yor own howsuz.” Soe of thae went. Thu ferst litul pig met u man with a loed of stror. “Pleez cood I hav sum ov yor stror,” he arskt poelietlee. “Sertunlee you fien yung pig,” sed thu man, and hee gave thu litul pig az much hae az he wontud. - Self-teaching: The key gift of regular orthographies: Wuns you no the GPCs, you can reed & riet orl werds. - - While our students are caught in lengthy early literacy, other nations’ students are flying in sophisticated literacy. - English orthographic complexity is extremely high (? too high). So is ‘the high cost of orthographic disadvantage! The importance of Orthographic Advantage Theory is revealed when English is compared with transparent orthographies. Slow progress by all readers Readers at end of Year 1 (& 2): Seymour, Aro and Erskine (2003) Transparent orthographies >90% accuracy: Norwegian Dutch Icelandic Swedish Spanish Italian Finnish Turkish German Greek Less transparent orthographies >70% accuracy: French Danish Portuguese Relatively opaque English 34% accuracy 34% accuracy in Year 1 76% accuracy a year later Greater weakness in delayed readers Landerl, Wimmer, & Frith (1997) English & German weak readers: English 16 times > vowel errors. German readers hardest words (3 syllable pseudowords) better than English readers easiest words (1 syllable real words) Huge difference in effectiveness of remediation & no. of „Treatment Resisters‟ (See bibliography: Torgesen, Vellutino, vs. Cossu, Schneider, Oloffson) Virtually no Treatment Resisters in transparent orthography nations: even severely disabled children develop fluent spelling & reading accuracy. Many (?most) Anglophone students with literacy weakness don‟t reach effortless fluency (esp in spelling). A large number make little progress despite extensive intervention Nations differ in their valuing of orthographic awareness Korea: High valuing & awareness Finland: Low valuing & awareness Australia: Low valuing & awareness SOPHISTICATED LITERACY INSTRUCTION 100% Lev5 Lev5 English Lev4 Korean Lev3 80% Lev4 Korean 60% Lev3 40% EARLY Lev2 LIT’CY INSTR’N 20% Lev2 Lev1 Lev1 ermany 10 yrs Taiwan tzerland <Lev1 elgium Estonia ?8+/-0.5yrs ermany Poland Taiwan Sweden 5 yrs tzerland erlands Estonia tenstein Poland NZ Sweden Ireland erlands Canada ustralia g Kong tenstein Finland NZ Korea elgium ustralia 0 yrs 0% Ireland English 15 yrs <Lev1 Korea shows high awareness of the impacts of orthographic complexity, having resolved orthographic complexity, with massive improvements at minimal expense. Hangul Day celebrates the bringing of literacy to the people. Centuries ago, King Sejong the Great demanded a simple system for writing spoken Korean so everyone could express their thoughts in writing. Finding nothing satisfactory in other nations, they made up their own set of symbols (Initially 11 Vs & 17 Cs, simplified in 1933 to 10 Vs & 14 Cs). Since the end of Japanese occupation, Hangul is the nation‟s sole writing system. “South Korea illustrates the pace of progress that is possible…. Two generations ago, the country had the economic output of Afghanistan today and ranked 24th in education output among the current 30 OECD countries. Today, South Korea is the world's top performer in secondary school graduation rates (93%). • Schleicher and Stewart (2008, p.45), in Galletly & Knight (In press) Korea was ‘Australia’ but with far less funds. Look at it now! Perhaps AUSTRALIA should focus > on Korea & < on Finland. Canada is the highest achieving Anglophone nation. NB Multilingualism seems to increase Orthographic Advantage. FINLAND shows low awareness. This is not a problem for them, though we get naive comments about ‘The Finnish Advantage’ Orthographic advantage is not currently recognised widely, e.g., it is not yet used as a variable by PISA analysts, who tout the Finnish advantage as • PISA 2006: FREEDOM of curriculum, assessment, and enquiry; EQUITY of learning opportunities; SAFETY; and TEACHER EDUCATION (Arinen, 2008). • PISA 2011: The Finnish Advantage: GOOD TEACHERS! From Orthographic Advantage perspectives, this is naive: • Finnish teachers have it easy: All students fluent readers and writers from early Grade 2. Homogenous high school classes without disengaged struggling readers. • In contrast, Australian teachers are excellent teachers: despite classes loaded with disengaged, reluctant readers, our teachers do so well that our high achievers pull our average up to 9th place in PISA reading, despite our >30% of students scoring poorly. AUSTRALIA shows low awareness, which hugely affects us via: 1. Suboptimal resourcing. 2. Suboptimal instructional emphases. A: English readers have multifaceted ‘Orthographic Disadvantage’ (Galletly & Knight, 2004) Compared to transparent orthography nations, we have Slower development of reading & writing. Delayed language development due to delayed equalisation of print: oral vocabularies. Delayed maturation of cognitive processing (phonemic & orthographic awareness). Delayed „full‟ emphasis on Sophisticated Literacy High heterogeneity of middle & upper school classes, due to many older students having reading & writing difficulties. The secondary impacts of enduring literacy low achievement, including disengagement, social-behaviour difficulties, and anxiety/depression. Work-place illiteracy, with its dangers and expense. Generational disadvantage: parents unable to read to their children. Extensive, expensive, ineffective remediation. Polarised achievement in international comparisons (lots of high achievers but also lots of low achievers. Low equity: strong linkage of SES & literacy achievement. Orthographic advantage seems equally strong in nations using transparent transitional orthographies! Nations which first teach a transparent orthography before moving to a more complex one, also get Orthographic Advantage, e.g., Taiwanese students have ceiling level phonemic awareness after 10 weeks of instruction. This is likely to expedite learning of logographic Kangi. Should we be using a transparent transitional orthography? Certainly our indigenous communities should be learning to read & write their fully transparent orthographies, rather than working with English first. Orthographic Advantage Theory (Galletly & Knight, 2004, 2011a, 2011b, In press) The regularity of the Orthography which a nation chooses to use strongly influences key aspects of nationwide literacy including • The Ease and Expense of successful Early Literacy instruction. • The richness of home literacy pre- and during school years. • The complexity of teaching circumstances across school years: Including the proportion of students with • Weak literacy • Weak language skills. • Disengagement & behaviour difficulties. • High needs for adult support and low adult: child ratios. • Rates of adult & workplace literacy difficulties. • Likelihood of success of reforms to improve reading. Q. What’s ‘Transition from Early to Sophisticated Literacy’ (TESL) paradigm? (Galletly & Knight, 2011a, 2011b, In press) ‘First we learn to read & write then we read & write to learn’’ (Chall, 1989) Stage 1: Early Literacy Development • Learning to Read & Write –strong emphasises on Text Decoder skills. Stage 2: Sophisticated Literacy Development • Reading and Writing to Learn (and communicate fluently) The Transition from Early to Sophisticated Literacy • Is strongly impacted by Orthographic Advantage/Awareness. • Has VIP implications for ease of instruction. SOPHISTICATED LITERACY INSTRUCTION English Korean Korean English EARLY LIT’CY INSTR’N 0 yrs 5 yrs ?8+/-0.5yrs 10 yrs 15 yrs 3 TESL (Transition from Early to Sophisticated Literacy) groups Ease of Transition 1. RAPID TRANSITION a. Resolved b. Facilitated Rapid Rapid Easy Easy 2. COMPLEX TRANSITION Slow Complex Orthography type Highly regular orthography A transitional highly regular orthography Less regular GPC orthographies. No. of GPCs Usually <50 GPCs ~1: 1 correspondence Usually <50 GPCs. 1: 1 correspondence. >500GPCs Many: many GPCs Nations using Korea. Most European China, Japan, Taiwan. Anglophone nations. this paradigm nations. Thailand. Complexity of Low Low V. High instruction Transitional used with Only a very small Words read All texts read. logographs, so: proportion of By endGr1 All words written. All texts read. all words. All words written. Ease for selfHigh. High. Low teaching Length of Brief: <<1yr for most Brief, <<1yr for most. Lengthy: 3 yrs to all Early Literacy school years. 3 TESL (Transition from Early to Sophisticated Literacy) groups 1. RAPID TRANSITION a. Resolved b. Facilitated Ease of v. successful Early Literacy Very easy Very easy 2. COMPLEX TRANSITION Very hard Very high due to Expense of Very low due to limited self-teaching Very low due to v. successful self- teaching hence needs for low self- teaching Early Literacy adult: child ratios LOW: >Homogenous LOW:>Homogenous HIGH:>Helerogenous Complexity of literacy needs, & literacy needs, & literacy needs, & Teaching probably less probably less probably less Circumstances disengagement & disengagement & disengagement & behaviour problems behaviour problems behaviour problems Likelihood of Low: High: Simpler educational High: Simpler teaching Teaching teaching reforms being circumstances. circumstances v. circumstances. successful Literacy needs Complex. Literacy needs homogenous & focused Literacy needs v. homogenous & on sophisticated literacy Hetergenous, & for focused on sophisticated literacy Early & Sophis’d lit’y Q. Did we misinterpret Freire? A: Yes! Freire expertly used Effective Principles of Instruction on all Dimensions of Learning to take Brazilian peasants from print illiteracy to being literate. He built Attitudes & Perceptions (DoL1. He also built mature orthographic awareness of all the orthographic content needed for Brazilian literacy (Letter sounds, & sounding-out) - he taught „Learning to Read & Write‟ using drills with decontextualised words (Dol2-3). This took an extremely short time, because the orthography is transparent. He then used „Reading & Writing to Learn‟ to continue Social Emancipation. We only noticed the empowerment. We didn‟t notice the careful explicit instruction using decontextualised words and word parts, until students were sufficiently competent to move on to independent reading & writing. If applying Freire to Australia, we should focus on Orthographic Awareness as well as empowerment. D1 Attitudes & Perceptions Acquire & Integrate New Knowledge D2 D5 Habits of Mind Extending & Refining Knowledge D3 Knowledge Development Using Knowledge Meaningfully D4 Q. What are the key aspects of change & instruction building Orthographic Awareness? At systemic & national levels: Gather more data: Go and See! Send teachers to observe transparent orthography classrooms in Korea, Finland, Wales, Estonia, Italy, etc. It is teachers, not academics, who are likely to notice pivotal instructional & achievement differences. Study the literacy development of bilingual groups using a highly transparent orthography, e.g. NZ Mauri, Australian indigenous languages. Study the changes in literacy achievement in nations which have changed their orthography in order to have orthographic advantage, e.g., Korea, some Russian nations. Consider the high costs of orthographic advantage & whether we can afford this cost, given it is a sociocultural choice our government has made (albeit unwittingly. In indigenous communities, change to bilingual education teaching reading & spelling of their first language first (Transparent orthographies from Wycliffe Bible Translators) PART 2: Ideas for Practice Key instructional implication: Build them together in a co-ordinated manner! Orthographic Awareness (Knowledge & Skills) Why be metacognitive about Orthographic Awareness? All 5 Dimensions of Learning (Marzano & Pickering) are VIP. For complex learning areas, basic learning (DoLs 2 & 3) is not sufficient. Metacognition (DoLs 4 & 5: higher-order learning) builds student ownership. Being metacognitive (using a framework of why, when, how) re Orthographic Awareness expands your teaching/learning zone (Vygotsky‟s ZPG) D1 D5 Attitudes & Perceptions Acquire & Integrate New Knowledge D2 Habits of Mind Extending & Refining Knowledge D3 Knowledge Development Using Knowledge Meaningfully D4 Are we emphasising Orthographic Awareness enough? What’s the fall-out of insufficient emphasis? Current curricula tend to assume Orthographic Awareness is needed only wrt Spelling, and little attention is focussed on optimising reading-accuracy. It‟s likely Spelling, Reading & Orthographic Awareness would be best improved by • A concentrated co-ordinated school-wide focus simultaneously building Reading-accuracy, Spelling and Orthographic awareness It’s time to embrace reading of decontextualised words! additives additionally activities additional actually addition When we paid for the dog, we additionally bought a bed, food & toys. We‟ve avoided reading decontextualised words. It‟s time to stop! Reading decontextualised words build orthographic awareness and spelling far more effectively than reading in context, as it‟s fully dependent on orthographic awareness. Message 1: Keep major foci on reading contextualised texts. Message 2: Add reading of decontextualised words. Why isn‟t context enough to support reading progress? • Orthographic awareness empowers reading of decontextualised words. • Both empower reading of contextualised text. • Whereas just over 100 'heavy duty' words (e.g., the, in, was, etc.) account for around half of all the letter strings appearing in printed school English, a very large number of words exist which appear very rarely in print (Carroll, Davies & Richman, 1971; Nagy & Anderson, 1984). • In fact fully eighty percent of English words occur less than once in a million words of running text (Carroll et al, 1971). (Share & Stanovich, 1995, p.15) Principles for building Orthographic Awareness Close the Print-verbal Vocabulary Gap: De-emphasise correct spelling in first-draft writing. Focus on „Getting your fine mind down on paper.‟ Build fluent writing of spelling approximations (“Brave Spelling”= Phonemic Equivalents), e.g. use Guestimating (Galletly, 2001) as an easy way to write unfamiliar words). Use scaffolded & unscaffolded reading texts for reading development. Use scaffolded reading texts for KLA work. (Guestimating Fun, pp.107-109 of Galletly, S. 2001 Two Vowels Talking) Steps for writing big words Teach the 3 rules • If you can say it on your fingers, you can write it. • Say every syllable as you write it. • Every syllable has a vowel. (Which one: I don‟t care. Step 1 is to get vowel spacers into multisyllabic words – dinuso animil Q. Principles for building Orthographic Awareness • Be aware that orthographic skill is evidenced & developed in 1.Spelling & spelling errors. 2. Word reading. 3.Discussing orthography, e.g., letters, sounds, GPCs. • Build skill in integrated instruction building reading accuracy, spelling & orthographic awareness in tandem, e.g. „Words their Way‟ seems a useful tool towards this end. • Consider teaching reading of a transitional orthography to bring phonemic awareness to a ceiling level, early in literacy development. E.g., Teach & practice Flexispel, then use it in scaffolding vocabulary in texts: photosynthesis (fo-to-sin-thu-sus), antique (an-teek), E.g., let‟s build national pride in use of an Indigenous language (perhaps Koori) used to label artifacts, etc. in the same manor that NZ uses English & Mauri (a transparent orthography) Q. Principles for building Orthographic Awareness • • Decontextualised words help: No context so must rely on orthography Will building „deeper‟ reading accuracy build orthographic awareness and therefore spelling? Rapid Reads Repeated reading of texts with errors on changed words. Build orthographic awareness using Spelling Grids 1C Sausages A lady went into a butcher shop complaining abowt the sausages she had just bought. ‘The middal is meat,” she exclaimed, ‘but the ends are sawdust!’ ‘Well,’ said the butcher, ‘theze days it’s hard to make ends meat.’ excellently interesting confident perfectly sure important 1 2 1D Sausages A lady went into a butcher shop complaining about the sossages she had jest bought. ‘The middle is meat,” she exclaimed, ‘but the ends are saudust!’ ‘Well,’ said the bootcher, ‘these days it’s hard to make ends meat.’ 3 4 5 6 7 8 explaining believed think agree convincing show A finnally thrid wy furst because another secand reezin B finally thurd wie first becors anuther seccond reasen need example amazingly asking final very C finilly therd why fearst becorse anothor second reeson extreme firmly disagree definitely opinions should D finelly third hwy ferst becuase annother seccand reason firstly because why second reasonable third Ones that tricked Will building metacognition about reading accuracy, spelling, & orthographic awareness boost all 3 areas? Yes! Orthographic Awareness (Knowledge & Skills) Emphasise 20 English Vowel Sounds 5 Vowel sounds ă bat ĕ bet ĭ bit ŏ bot ŭ but 5 Vowel NAMES ā mate ē Pete 5 ar tar or for ī bite R ō hope ū tube Vowels er her air hair ear dear 5 other Vowels Would you boys show/er? oo1 good oo2 food oi boil ow cow schwa (ə) again tiger Building Early Years’ Orthographic Awareness Teach letter name categories: • Sound at start of name (B K Z), • Sound at end (F M X), • Sound not in name (H Y W). Teach that all letters have 5 concepts 1. A Name, 2. Sound/s, 3. A Capital, 4. A Lowercase, 5. You find it in words. Emphasise three grain sizes in words & syllables: 1. Regular words (phonemes): • Letter-sound knowledge - know 5 to 7 letters (name, sound, capital, lowercase, find/hear it in words).. • Early phonological awareness - blending 3 sound words, onset-rime listing, isolating initial/final/vowel sounds. 2. Pattern words (rimes): • Build fluent rhyming (rapid rhyming of real and nonsense words sam-bam-lamtam-wam) • Match written pattern words (rhyming words) 3. Whole words • • • • Word constancy - know 5 sight words (Family name snap, preschool pets, etc) Notice them in books and games. Use the vocabulary during reading activities and book reading (listed above). These skill are developed through play activities, with no need for drill. Teach words having 3 grain-size categories: • Explore how words move from being Tricky to being Pattern/Regular words as Orthographic Awareness builds. Build Metacognitive Orthographic Awareness • • • • • • Find the ways (GPCs) we write our commonest vowel sound (the schwa: Ə, as in tiger virus began moutain). We have 6 signatures of Shakespeare – each spelled differently. Today when I mark the roll, reply by spelling your name a new way. Find how many ways we write /or/ in different words.( >>10). Explore the ≥ 20 common vowel sounds of Australian English Learn Dr G‟s 2 rulz of Inglish speling: Inglish spelling iz syllee kumpaired to sensubul speling nashuns! • = I‟m not stupid. English spelling is! Inglish speling iz fassinayting! = You‟ll never master English spelling if you‟re not interested in it. Be fascinated. Keep finding more exciting patterns. Find spelling rules vs exception words using a convention of „If a pattern is in ≥ words, it‟s a rule.‟ Run a Middle School (Y5-9) unit building from Dr G‟s rulz, using Flexispel‟s stages, exploring the history of English writing & orthography, and discovering and mapping rules & exceptions. Bibliography Aro, M. (2004). Learning to read: The effect of orthography. Jyvaskyla, Finland: University of Jyvaskyla. Bryson, B. (1990). Mother tongue. London: Penguin Books. Chall, J. S. (1989). Learning to read: The great debate 20 years later - a response to "Debunking the great phonics myth". Phi Delta Kappa, 70, 521-538. Cossu, G. (1993). When reading is acquired but phonemic awareness is not: A study of literacy in Down's syndrome. Cognition, 46, 129-138. Cossu, G. (1999). The acquisition of Italian orthography. In M. Harris & G. Hatano (Eds.), Learning to reading and write: A cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 10-34). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Galletly, S. A. (2004). Reading accuracy and phonological recoding: Poor relations no longer. In B. Knight & W. Scott (Eds.), Learning Disabilities: Multiple Perspectives. Melbourne: Pearson Education Australia. Galletly, S. A., & Knight, B. A. (2004). The high cost of orthographic disadvantage. Australian Journal of Learning Disabilities, 9, 4-11. Galletly, S. A., & Knight, B. A. (2011a). Transition from Early to Sophisticated Literacy (TESL) as a factor in cross-national achievement differences. Australian Educational Researcher. Galletly, S. A., & Knight, B. A. (2011b). A theory of differential disadvantage of Anglophone weak readers with language and cognitive processing weakness. Australasian Journal of Special Education. Galletly, S. A., & Knight, B. A. (In press b). Because trucks aren’t bicycles: Orthographic complexity as an important variable in reading research. Australian Educational Researcher. Galletly, S. A., Knight, B. A., Dekkers, J., & Galletly, T. A. (In press). Indicators of late emerging reading-accuracy difficulties in Australian schools. Australian Journal of Teacher Education. Bibliography (continued) Galletly, S. A. (1999). Sounds & Vowels: Keys to literacy progress. Mackay, Qld, Australia: Literacy Plus. Galletly, S. A. (2001). Two vowels talking: Keys to literacy progress. Mackay, Australia: Literacy Plus. Gathercole, S. E., & Pickering, S. J. (2000). Working memory deficits in children with low achievements in the national curriculum at 7 years of age. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 177-194. Goswami, U. C. (2002). Phonology, reading development, and dyslexia: A crosslinguistic perspective. Annals of Dyslexia, 52, 141-163. Hanley, J. R., Masterson, J., Spencer, L. H., & Evans, D. (2004). How long do the advantages of learning to read a transparent orthography last? An investigation of the reading skills and incidence of dyslexia in Welsh children at 10-years of age. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 57, 1393-1410. Holopainen, L., Ahonen, T., & Lyytinen, H. (2001). Predicting delay in reading achievement in a highly transparent language. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34, 401-413. Jimenez, J. E., Siegel, L. S., & Lopez, M. R. (2003). The relationship between IQ and reading disabilities in English-speaking Canadian and Spanish children. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 36, 15-23. Landerl, K., Wimmer, H. C. A., & Frith, U. (1997). The impact of orthographic consistency on dyslexia: A German-English comparison. Cognition, 63, 315-334. Leach, J. M., Scarborough, H. S., & Rescorla, L. (2003). Late-emerging reading disabilities. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 211-224. Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (2000). Further Notes on the Four Resources Model. Reading Online. Downloaded on 27 Feb 2009 from www.readingonline.org/research/lukefreebody.html. Bibliography (continued) Lyytinen, H., Aro, M., Eklund, K., Erskine, J. M., Guttorm, T., Laakso, M.-L., et al. (2004). The development of children at familial risk for dyslexia: Birth to early school age. Annals of Dyslexia, 54, 184-220. Olofsson, A., & Niedersoe, J. (1999). Early language development and kindergarten phonological awareness as predictors of reading problems: From 3 to 11 years of age. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32, 464-472. Poskiparta, E., Neimi, P., & Vauras, M. (1999). Who benefits from training in linguistic awareness in the first grade, and what components show training effects? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32, 437-447. Schneider, W., Ennemoser, M., Roth, E., & Kuspert, P. (1999). Kindergarten prevention of dyslexia: Does training in phonological awareness work for everybody? Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32, 429-442. Seymour, P. H. K., Aro, M., & Erskine, J. M. (2003). Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 143-174. Torgesen, J. K. (2000). Individual differences in response to early interventions in reading: The lingering problem of treatment resisters. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 15, 55 - 65. Vellutino, F. R., Scanlon, D. M., Sipay, E. R., Small, S. G., Pratt, A., Chen, R., et al. (1996). Cognitive profiles of difficult-to-remediate and readily remediated poor readers: Early intervention as a vehicle for distinguishing between cognitive and experiential deficits as basic causes of specific reading disability. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 601638. Venezky, R. (2004). In search of the perfect orthography. Written Language & Literacy, 7, 39–63. Ziegler, J. C., & Goswami, U. C. (2005). Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia and skilled reading across languages: A psycholinguistic grain size theory. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 3-29.

© Copyright 2026