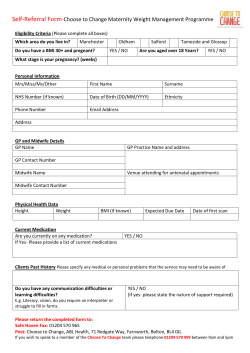

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF OVER ADUL