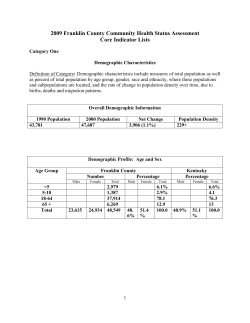

Document 57173