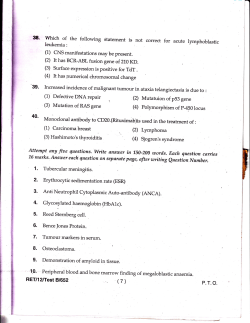

R DOWN SYNDROME EPORT OF THE