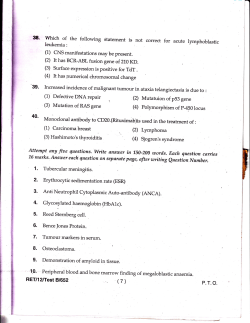

Information about Down syndrome