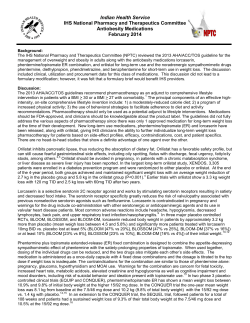

2013 F as in Fat: How Obesity Threatens