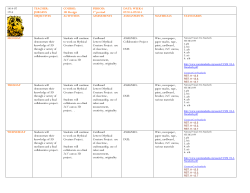

Document 63139