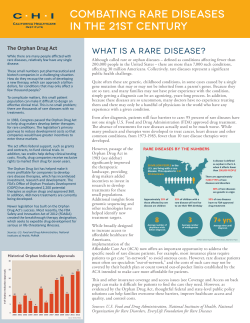

Experiences of Rare Diseases: An Insight from Patients and Families