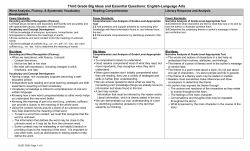

This is the first of a block of six narrative... experience and knowledge from Year 4 and introduces new areas... Year 5 Narrative - Unit 1