Pulse Cyclophosphamide Therapy for Refractory

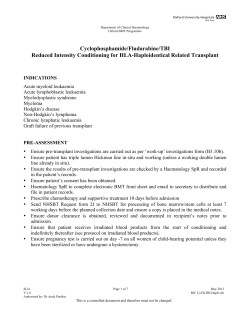

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on December 29, 2014. For personal use only. Pulse Cyclophosphamide Therapy for Refractory Autoimmune Thrombocytopenic Purpura By Alex Reiner, Terry Gernsheimer, and Sherrill J. Slichter Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura (AITP) is generally a chronic disorder in affected adults. Twenty-five percent of these patients will become refractory t o routine therapy (corticosteroids and splenectomy), as well as most other available agents. Intravenous pulsecyclophosphamide therapy was used t o treat 20 patients with severe refractory AITP who hadpreviously failedt o achieve a sustained remission with a mean of 4.8 agents (range 2 t o 8). Patients received 1 t o 4 doses (mean 2.0) of 1.0 t o 1.5 g/m2 intravenous cyclophosphamide per course. Of the 20 patients treated with pulse cyclophosphamide therapy, 13 patients (65v0) achieved a complete response (CR),four (20%) a partial response (PR), and three patients (15%) failed t o respond. Of the 13 complete responders, eight have remained in remission with stable platelet counts during followup intervals of 7 months t o 7 years (median 2.5 years). Five patients developed recurrent AITP 4 months t o 3 years following a CR.Of these, two patients responded t o subsequent courses of pulse cyclophosphamide therapy with current remissions of 1 and 4 years. Of the four patients who obtained a PR, two remain in partial remission after 10 months and 4 years; one relapsed after 18 months and, after retreatment, is still in remission at 6 months. Of the patient characteristics examined, duration of disease was most strongly associated with response t o pulse cyclophosphamide. Side-effects of treatment included neutropenia (three patients, one of whom developed staphylococcal sepsis), acute deep venous thrombosis (two patients), and psoas abscess (one patient). Intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide should be strongly considered in the treatmentof patients with refractory AITP. There is a relatively low incidence of side-effects, and it can be administered easily on an out-patient basis. 0 7995 by The American Societyof Hematology. A lier study by Weinerman, et alZ6indicated a beneficial effect of pulse cyclophosphamide in eight of 14 patients with AITP. Seven years ago, we treated our first patient-a 15 year old girl with severe refractory AITP who suffered an intracranial hemorrhage-with pulse cyclophosphamide, and she remains in long-term remission. We now report our experience using pulse cyclophosphamide to treat 19 additional severely-affected, highly-refractory AITP patients. UTOIMMUNE thrombocytopenic purpura (AITP) is a disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia with shortened platelet survival, normal to increased numbers of bone marrow megakaryocytes, and elevated levels of platelet-associated immunoglobulin G (IgG).”’ Women are more commonly affected than men. Bleeding manifestations are variable, but are more likely to occur in older patients and those with severe thromb~cytopenia.~.’ AITP is caused by autoantibodies directed against platelet membrane glycoproteins (eg, GPIIb-IIIa, GPIb)*s9 that result in both removal of the antibody-coated platelets from the circulation by the reticuloendothelial system’0,” and defective platelet production and/or release of platelets from the bone ~ Z U T O W . ’ ~ - ’ ~ Initial therapy of AITP consists of corticosteroids, often combined with intravenous gammaglobulin (W IgG) in severe episodes. There is a great predominance of the chronic form of the disease in the adult patient’’ and most will ultimately require other forms of therapy, most commonly splenectomy. Together, corticosteroids and splenectomy induce long-term responses in about 75% of chronic AITP patients.I6 The remaining 25% of patients who are refractory to standard therapy constitute a subgroup with a significantly higher mortality rate compared with those who respond to corticosteroids and/or splenectomy.’6 Other treatment options are available for patients with refractory AITP,but response rates 2re generally low and unpredictable. The initial response rates for other agents such as vinca alkaloids, danazol, low-dose oral cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and colchicine are less than 50%, with long-term response rates much lower.I6 More recently, other agents such as a-interferon,” cyclosporine,’*IV IgG,” ascorbic acid:” staph protein A immunoadsorption:’ anti-Fc receptor monoclonal antibody:‘ and combination chemotherapyz3have been used in the treatment of refractory AITP, but the utility of these agents either has been unsatisfactory or remains to be confirmed in larger clinical trials. Intermittent intravenous cyclophosphamide (pulse therapy) has been reported as an effective treatment for various autoimmune diseases including nephritis associated with systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE).”.25In addition, an earBlood, Vol85, No 2 (January 151,1995: pp 351-358 MATERIALS AND METHODS Patient selection. Because of our interest in the care and management of patients with AITP, we are often consulted by community physicians to discuss treatment options for their patients with refractory disease. Based on our success with the initial patient (patient no. 1) treated with pulse cyclophosphamide, subsequent referrals were routinely advised to initiate a similar therapeutic regimen. The diagnosis of AITP in the study patients was made on the basis of thrombocytopenia unrelated to any underlying viral infection, collagen vascular disease, malignancy or medication, morphologically normal bone marrow aspirate with normal to increased numbers of megakaryocytes, and absence of splenomegaly. Patients were considered for therapy if either: (1) during an acute initial or recurrent episode of AITP, platelet counts could not be increased to a safe level despite treatment with multiple modalities; or (2) if chronic AITP could not be managed with acceptable doses of corticosteroids or other agents. From Puget Sound Blood Center: and theDivision of Hematology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA. Submitted May 2, 1994: accepted September 15, 1994. Supported by Grant No. HL 47227 fromthe National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. Address reprint requests to Sherrill J. Slichter, MD, Director, Medical & Research Division, Puget Sound Blood Center, 921 Terry Ave. Seattle, WA 98104-1256. The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to indicate this fact. 0 1995 by The American Society of Hematology. oooS-497I/s5/8502-0014$3.00/0 35 1 From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on December 29, 2014. For personal use only. 352 Pulse cyclophosphamide therapy. Each treatment course of high-dose cyclophosphamide therapy consisted of 1.0 to I .5 g/m' of cyclophosphamide given by rapid intravenous infusion and repeated at four-week intervals. The number of doses administered per treatment course ranged from one to four, with a meanof 2.0. At the time of initiation of cyclophosphamide therapy, all patients were simultaneously receiving corticosteroids, and several were receiving other agents as well. Treatment response criteria Clinical response to cyclophosphamide wasdefined as follows: complete response (CR) = platelet X IO9& partial response (PR) = increase in platelet count ,150 count to 2 5 0 X 109/L;or no response (NR). Platelet antibody assays. Platelet-associated and free circulating platelet antibodies were detected using both '2sI-radiolabeled(RIA) and enzyme-linked (ELISA) platelet antiglobulin assays. The direct assay was performed using the patient's autologous platelets if the platelet count was above 10 to 20 X 109/L. In the indirect assays, patient serum was tested against platelets from one or more random normal group 0 blood donors. Data is not reported for the indirect assays unless the patient had never beenpreviously pregnant or transfused so that an alloantibody reacting with donor platelets could be excluded as the basis for a positive test result. Peripheral whole blood collected in 10% potassium-EDTA was centrifuged at 350s for 10 minutes to obtain platelet-rich plasma from patients or random donors. For the ELISA platelet antiglobulin assays, the platelets were washed three times with 0.01 mol/L Tris pH 7.5 containing 0.145 mol/L NaCl and 1 mmol/L EDTA, and the platelet concentration was adjusted to 100 X IOY/L. Five X 10' platelets were added to wells of a 96-well microtiter plate (NUNC, Roskilde, Denmark). The platelets were bound to the wells by centrifugation at 1 0 0 0 ~ for 10 minutes. Plates were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), then blocked with 100 pL of 5% human albumin (New York Blood Center, Melville, N Y ) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Fifty pL of fresh (less than 24 hours old) patient or pooled normal serum diluted 1:2and 1:4 in5% human albumin was added to the microtiter wells of each platelet sample and incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes. Plates were then washed six times with PBS, and 50 pL of one of four different alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antiglobulin reagents diluted in 5% human albumin were added and incubated at room temperature for 30 minutes. The four detecting reagents were: (1) monoclonal antihuman IgG (ICN Biomedicals, Costa Mesa, CA) diluted 1 :800; (2) monoclonal antihuman IgG, (The Binding Site, Birmingham, UK) diluted 1:400; (3) goat antihuman IgM (Sigma, St Louis, MO) diluted 1:500; and (4) Staph Protein A (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) diluted 1:800. After washing six times with PBS, 50 pL of substrate (3.4 mg/mL p-nitrophenylphosphate in 0.05 m o l n carbonate 1 mmol/LMgCl, pH 9.8) was added to each well; the platelets were sealed with plastic sealing tape and incubated at 37°C for 50 minutes. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 pL of I mol/L NaOH. Absorbance was measured using a Bio-Tek microtiter plate reader (Winooski, VT). A positive platelet antibody result is indicated if the OD is over two standard deviations above that of the pooled normal serum for any of the four detecting reagents. Serum pools were obtained from 20 to 30 previously untransfused male donors who were type A or AB. In our laboratory, the coefficient of variation of the OD for pooled normal serum is approximately 30%. Reference alloantisera wereused for standardization of the ELISA and as positive controls. The platelet antiglobulin radioimmunoassay was performed using '251-labeled anti-IgG and anti-C, asthe detecting reagents as described previously." An elevated level of platelet antibody detected using any one (or more) of thesix total antiglobulin reagents in either the ELISA or theRIAwas considered a positive platelet antibody test. REINER,GERNSHEIMER, AND SLICHTER RESULTS Patient characteristics. The clinicalcharacteristics of the 20 patientswith refractory AITP treated with pulse cyclophosphamide are shown in Table 1. Fourteen patients were women, and sixwere men. Patient ages ranged from 15 to 79 years with a mean of 50 years. Concurrent diseases included diabetes mellitus in three patients (no.8, 13, and 20), autoimmune hemolytic anemia in two patients(no. 14 and 16), hypothyroidism in two patients (no. 6 and 14), and multiple sclerosis in one patient (no. 2). One of nine patients tested had a positive antinuclear antibody (ANA; patient no. 10). The median duration of AITP before pulse cyclophosphamide therapy was six months and ranged from one month to 28 years. Bleeding manifestations were present in 16 patients. These mainly consisted of skin and mucosal bleeding, except for patient no. 1 who suffered an intracranial hemorrhage. Of the 20 patients, nine received pulse cyclophosphamide during theirinitial episode of AITP (patients no. I through g), while 11 weretreated during an AITP relapse (patients no. 10 through 20). Of the latter patients, four were in first relapse (no. I I through 14), one was in third relapse (no. lo), and six patients had long-standing recurrent AITP with fouror morerelapses (no. 15 through 20).The20 patients had beentreatedpreviously with a mean of 4.8 different agents (range,2 to8)before cyclophosphamide therapy. All 20 patients had received corticosteroids, and 19 had undergone splenectomy. Two patients had also undergone an accessory splenectomy (no. I8 and 20). Other previous therapies included vinca alkaloids ( 1 5 patients), IV IgG (IS patients),danazol (8patients), plasmapheresis (4 patients), anti-D IgG (3 patients), low-dose oral cyclophosphamide (3 patients),azathioprine (3 patients), colchicine(2 patients), and ascorbic acid,ProteinAimmunoadsorption, and vinca-loaded platelets ( I patient each). In addition to corticosteroid therapy, I3 courses of cyclophosphamide were administered concurrently with IV IgG, three courses with danazol, and one course with vincristine. In patients no. 10, 1 I, and 16, danazol had been administered for 3 weeks, 10 weeks, and10 days before initiation of pulse cyclophosphamide therapy,respectively,without evidence of an increase in platelet count. Although patient no. 10 had transiently responded to vincristine, he had been receiving this agent for 1 month before initiation of pulse cyclophosphamide without effect. The mean nadir platelet count precyclophosphamide for the 20 patients was 7 X I O 9 L (range, I to20 X l0'L) (Table 2). At the time of initiation of cyclophosphamide therapy,themeanplatelet count was 68 X I O ' L (range, I to 534 X IOq/L). This elevation from baseline was due to the acute effect of IV IgG or high-dose corticosteroids in six of the patients. Response to pulse cyclophosphamide therapy. Responses of the 20 refractory AITP patients to pulse cyclophosphamideare illustrated in Fig 1 andsummarized in Table 2. The meanpeakplatelet count followingthe27 treatment courses of pulsecyclophosphamidewas261 X 1 0 " L (range, 6 to 745 X lo9&). Based onour response CR. four(20%) criteria, 13 patients (65%) achieveda From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on December 29, 2014. For personal use only. PULSE FOR AITP 353 Table 1. Patient Characteristics and Previous and Concurrent Therapy Patient No. 5 F166 F165 F11 1 2 3 4 SexIAge FP7 M128 5 MI24 6 7 8 9 10 F141 F115 F159 M164 Duration of AITP Bleeding Manifestations* Previous Therapy 4 m0 Epistaxis, GU, intracerebral GU Skin, epistaxis Epistaxis, gingival, GU Skin, epistaxis Skin, gingival GI Epistaxis, GU None None 6 m0 6 m0 8 mo Skin Skin Skin, gingival CS, 1 m0 1 mo 1 mo 1 mo 2 mo 2 mo 4 m0 6 m0 8 mo CS, CS, CS, CS, CS, CS, CS, CS, CS, CS, splen, va, vlp, IV IgG. pher splen, va, IV IgG, anti-D, pher splen, IV IgG splen, IV IgG splen, va, IV IgG IV IgG, pher splen, va, dz, IV IgG, colch, aa splen, va, IV IgG splen splen, va, IV IgG splen, va, dz, IV IgG, aza splen, va, dz, Id cy splen, dz 11 12 13 W42 14 15 F136 F140 2 yr Epistaxis None CS, 3 vr CS, splen, va, IV IgG splen, va, dz, IV IgG, aza, pher, prot A 16 F138 5 vr Skin, gingival, GU CS. splen, dz, va, 17 M179 6 yr GU Epistaxis, va CS, splen, 18 19 F151 Mi7 1 10 yr 15 yr CS. 20 FP2 28 yr None Skin, epistaxis, conjunctival GU Mi75 F134 CS, CS, IV IgG, colch Current Therapy CS CS, IV IgG CS CS, CS, IV IgG IV IgG CS CS CS IV IgG a) CS, va, IV IgG b) CS, dz c) IV IgG CS, IV IgG, dz CS, IV IgG a) CS b) None CS, CS a) CS b) CS, a) CS, b) CS, c) CS, a) CS, IV IgG dz IV IgG IV IgG IV IgG b) CS CS, CS. splen, va, dz, IV IgG, aza, anti-D splen, va, Id cy, IV IgG, anti-D CS, splen, va, dz, Id cy CS IV IgG CS Concurrent therapy is listed foreach treatment course of pulse cyclophosphamide received by each patient. a, b. and c represent sequential treatment programs in the same patient. Abbreviations: CS, corticosteroids: splen, splenectomy; va, vinca alkaloids; dz, danazol; Id cy, low dose cyclophosphamide; aza, azathioprine; anti-D, anti-RhD; colch, colchicine; aa, ascorbic acid; vlp, vinca-loaded platelets; protA, protein A immunoadsorption: pher, plasmapheresis; !V IgG, intravenous immune globulin; GU, genitourinary; GI, gastrointestinal. * Bleeding manifestations at the time of initiationof pulse cyclophosphamide. achieved a PR, and three (15%) had NR; thus, the overall response rate to the first treatment course with pulse cyclophosphamide was 85%. The mean time to response was 7 weeks and ranged from 1 to 16 weeks. Of the 13 complete responders, eight have remained in remission with stable platelet counts during followup intervals of 6 months to 7 years (median, 2.5 years). This includes the index patient (no. l), who fully recovered from an intracranial hemorrhage and has been well for 7 years. Five patients developed recurrent AITP 4 months to 3 years following a CR. Of these, two patients (no. 13 and 16) responded to subsequent courses of pulse cyclophosphamide. Patient no. 13 relapsed after 9 months, then achieved a second CR with pulse cyclophosphamide that has persisted for 4 years. Patient no. 16 relapsed 3 years after her first CR with pulse cyclophosphamide, then achieved a second CR with pulse cyclophosphamide that lasted 10 months and finally a third CR, which has persisted for 1 year. Adding these two patients to the eight who remain in CR after their first treatment course with pulse cyclophosphamide gives a long-term CR rate of 10120 or 50% with a median followup of 2.5 years. Five of these patients responded during their initial episode of AITP, and five of these were patients with a history of relapsed AITP. The three other patients who relapsed after a first CR to pulse cyclophosphamide also received additional courses of pulse cyclophosphamide. Patient no. 15 relapsed 9 months after her CR, then responded very briefly to a second treatment course with pulse cyclophosphamide. She subsequently failed trials of methotrexate, a-interferon, 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine, and Protein A immunoadsorption. Currently, her platelet count is maintained above 50 X 109Lon a single dose of IV IgG repeated every three weeks. Patient no. 10 relapsed 4 months after his first CR, achieved a second CR with pulse cyclophosphamide that lasted 5 months, then received a third treatment course with pulse cyclophosphamide without response. He subsequently failed a trial of anti-D and, over the past several years, has had several more recurrences of AITP that respond variably to a combination of corticosteroids, IV IgG, low-dose cyclophosphamide, and danazol. Patient no. 2 relapsed 1 year after her CR. Because her first treatment course of pulse cyclophosphamide was complicated by severe neutropenia and staph sepsis, she was begun on intravenous cyclophosphamide at a lower dose of From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on December 29, 2014. For personal use only. 354 GERNSHEIMER, REINER, AND SLlCHTER Table 2. Response to Pulse Cyclophosphamide Therapy No. of Doses/ Patient No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10a 10b 1oc 11 12 13a 13b 14 15a 15b 16a 16b 16c 17a 17b 18 19 20 Treatment Pre* Count Program Time to X 1091~ l <l 1 2 1 2 3 3 4 2 2 2 1 3 2 1 2 2 2 3 2 1 1 2 2 4 2 3 1 4 4 6 6 9 5 6 9 14 2 9 8 20 16 6 3 12 10 9 5 10 20 10 6 5 Postt Count x 109/L Response 530 215 56 198 369 180 79 67 457 315 377 10 260 10 146 400 440 373 176 547 745 279 124 63 390$ 6 234 CR CR PR CR CR CR PR PR CR CR CR NR CR NR CR CR CR CR CR CR CR CR PR PR NR NR CR Response (wk) 4 8 10 1 10 9 6 16 8 Response 7 vr 1 vr 4 vr 8 mo 7 vr 6 mo 10 mo 5 mo 2 2 vr 4 mo 5 mo 16 3 vr 2 8 6 8 6 4 2 2 10 10 9 mo 8 8 Status Current Duration 4 vr 1 vr 9 mo 2 mo CR Deceased (unknown cause) PR CR CR CR PR Deceased (complications of diabetes) CR PR t o dz, Id cy, CS, IV IgG CR Deceased (bleeding; refused additional therapy) CR CR PR t o IV IgG 3 Yr 10 mo 1 vr 18 mo 6 m0 5 yr CR PR CR to prot A Deceased (complications of another therapy) CR a, b, c, represent sequential treatment programs in the same patient. Abbreviations: CR. complete response; PR, partial response; NR, no response; dz, danazol; Id cy, low dose cytoxan; IgG, intravenous immunoglobulin; prot A, protein A immunoadsorption. * Nadir platelet count precyclophosphamide. t Peak platelet count postcyclophosphamide. Represents transient response to IV IgG. CS, corticosteroids; IV * 500 to 750 mg weekly. The patient died two months later of unknown causes while in a nursing home with a platelet count of 32 X 109/L. Four of the 20 patients achieved a PR following their first treatment course of pulse cyclophosphamide. Two of these patients (no. 3 and 7) remain stable off all medications after 4 years and 10 months, respectively. Patient no. 3 presented with a platelet count of <S X 109/Lassociated with intermittent epistaxis and bruising. She initially responded to pulse cyclophosphamide with a platelet count of 50 X 109/Lthat persisted for 6 months. Her platelet count subsequently decreased to 20 X lo9& but she has maintained a platelet count in this range off all medications with resolution of bleeding symptoms for the past 4 years. Patient no. 8 relapsed 5 months after a PRto cyclophosphamide therapy and died 1 month later of complications of diabetes mellitus. Patient no. 17 relapsed 18 months after a first PR, then achieved a subsequent PR that has been stable for 6 months off all therapy following a second treatment course of pulse cyclophosphamide therapy. Three patients with chronic recurrent AITP failed to respondto pulse cyclophosphamide therapy. All were previously refractory to corticosteroids, splenectomy, danazol, and vincristine therapy. Two patients had failed to respond to anti-D. Two had previously failed therapy with low-dose oral cyclophosphamide. Patient no. 18 has since achieved a CR with Protein A immunoadsorption that has persisted for two months. Patient no. 12 was refractory to corticosteroids, splenectomy, and IV IgG, then responded transiently to vincristine and danazol. He failed to respond to either low-dose oral or intravenous pulse cyclophosphamide therapy and died 3 months later with a platelet count of < l 0 X 109/L of uncontrolled hemorrhage and anemia after refusing further supportive transfusion therapy. Patient no. 19 died of complications following treatment with an anti-Fc receptor monoclonal antibody. Plateletantibody data. Platelet antibody studies were performed for 12 of the 20 patients before pulse cyclophosphamide treatment. Platelet-associated antibodies were detected in l l of these 12 patients. Ten of the patients had free, circulating platelet antibodies. Interestingly, the one patient who was negative for both platelet-bound and free antibody (no. 19) did not respond to pulse cyclophosphamide therapy. Response versus patient characteristics. The relationship of several patient variables to their initial treatment From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on December 29, 2014. For personal use only. 355 PULSE CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE FOR AITP 800 l 600 /I 400 200 Pre Post Fig 1. Platelet responses to pulsecyclophosphamide.Thenadir precyclophosphamide platelet countandpeakpostcyclophosphamMe platelet count is plotted for each patient. For patients treated with more than one course, the resutts of each treatment is represented. response to pulse cyclophosphamide is summarized in Table 3. Because of the small number of patients (particularly in the NR category), firm conclusions cannot be drawn. The duration of AITP appears to be the strongest determinant of patient response to pulse cyclophosphamide. The median duration of AITP in responders (CR + PR) versus nonresponders is 6 months versus 10 years ( P value = .l0 by Mann-Whitney rank sum test). While nine patients treated during their initial episode of (primary) AITP as well as eight patients with recurrent AITP responded to pulse cyclophosphamide, the three non-responders all had recurrent AITP ( P value = .22 by Fisher exact test). From the data in Table 3, there is also a suggestion that women and younger patients respond better to pulse cyclophosphamide ( P values = .20 and .15, respectively). Finally, when the 27 treatment courses of pulse cyclophosphamide are analyzed individually, there is no correlation between number of doses and treatment outcome. Complications of pulse cyclophosphamide therapy. Side-effects occurred during six of the 27 treatment courses (22%). Neutropenia was the most frequent complication of pulse cyclophosphamide therapy and occurred during three of the 27 treatment courses (11%). In two patients (no. 3 and 15), the neutropenia was mild (nadir neutrophil count 1.0 and 1.5 X lo9&, respectively). Patient no. 2, however, developed severe neutropenia (neutrophil count = 0.1 X lo9/ L) complicated by an episode of staphylococcal sepsis. This patient eventually recovered and maintained a CR for one year, but subsequently died shortly after a second course of cyclophosphamide given at a lower dose (500 to 750 mg weekly). The cause of death is unknown. Two patients (no. 10 and 16) developed acute deep venous thrombosis coincident with a rapid CR to therapy (platelet counts of 298 X 109/Land 745 X lo9&, respectively, at the time of the thrombosis). No known risk factors for venous thrombotic disease were present in either patient. Finally, patient no. 17 developed a psoas abscess following the first dose of pulse cyclophosphamide, necessitating a delay of the second dose by 6 weeks. The psoas abscess was not accompanied by neutropenia in this patient, but he had been receiving prolonged therapy with corticosteroids. Following a relapse 1 year later, the patient received another two doses of pulse cyclophosphamide therapy without complications and again attained a PR. Although 12 of the 27 cyclophosphamide treatment courses were initiated while patients were hospitalized because of their bleeding manifestations and low platelet counts, patients who were more stable could be treated as outpatients because of the low incidence of side-effects. No long-term side-effects of pulse cyclophosphamide have been noted in any of our patients to date. In particular, none of the 20 patients have developed a secondary malignancy (median followup since first cyclophosphamide dose is 2 years, range 3 months to 7 years). DISCUSSION We report the responses of 20 clinically-severe and highly-refractory AITP patients to pulse cyclophosphamide. Bleeding symptoms were present at the time of treatment in 16 patients, including intracranial bleeding in the initial patient. More than halfof the patients had recurrent A m , including six patients with chronic, long-standing AITP marked by four or more relapses. Furthermore, all the patients had been heavily treated before receiving pulse cyclophosphamide. Each patient had failed to respond to an aver- Table 3. Patient Characteristics Based on Response to Treatmant CR Sex (WM) 112 311 Mean age (yr) AITP median duration Priman//Recurrent Mean no. doses cyclophosphamide Presence of antibody (n = 13) PR (n = 4) 1013 46 6mo 617 1.9 7/7 50 5mo 311 2.6 3/3 NR (n = 3) 66 10yr OB 2.3 1/2 From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on December 29, 2014. For personal use only. 356 age of 4.8 different agents, including corticosteroids in all 20, and splenectomy in 19. The evaluation of patient responses to pulse cyclophosphamide may be complicated by two factors. First, approximately five toten percent of patients with AITP recover spontaneously.’h~’7~28 However, the fairly short and predictable time interval between pulse cyclophosphamide treatmentand rise in platelet count (mean 8 weeks after first dose) in most of our patients is consistent with a therapeutic effect. Second, in a few of our patients, evaluation of response to cyclophosphamide may be complicated by a short time interval between previous therapies and administration of cyclophosphamide, or by concurrent treatment with other agents. In three patients treated during an initial episode of AITP (no. 1, 2 and 5), the interval between vinca alkaloid treatment and initiation of pulse cyclophosphamide was relatively short, but vinca alkaloids rarely induce a long-term response. Almost half of the 27 treatment courses were administered concurrently with intravenous IgG, butnotin doses reported to induce a long-term response.” Four cyclophosphamide responses were associated with concurrent danazol (patients no. 10, 11, and 16) or vinca alkaloid therapy (no. lo), but the interval toand duration of response are more consistent with a response to pulse cyclophosphamide therapy. In this series of 20 highly refractory patients, 17 patients had either a CR or PR to their initial course of pulse cyclophosphamide (one to four doses of 1 to 1.5 g/m2) for an overall response rate of 85%. Furthermore, 10 patients (50%) in the series have had a sustained response to their initial treatment. In addition, three of the initially-responsive patients who relapsed responded to a second and/or third treatment course of pulse cyclophosphamide and are currently stable. Thus, the cumulative long-term response rate is 13 of 20 (65%) with a mean followup of 2.9 years. These results are superior to those of standard secondary AITP agents such as vinca alkaloids, danazol, oral cyclophosphamide, and azathioprine. At best, these agents have response rates of approximately 50%, but sustained response rates are in the range of only 5 to 25%.16 Our favorable results with pulse cyclophosphamide are comparable to three other studies. Figueroa, et al’’ recently reported responses in eight (six complete, two partial) of 10 severely-affected, highly-refractory AITP patients treated with cyclophosphamide-based combination chemotherapy. Five of the responses (four complete and one partial) were sustained. These patients received between 3 and 8 monthly cycles of a chemotherapy regimen that included cyclophosphamide at total doses approximately the same asusedin our study (-0.5 g/m’ given every 2 weeks) and corticosteroids along with either vincristine, procarbazine, and/or etoposide. Our data suggest that the most important component of these combined treatment regimens was cyclophosphamide, and that the other agents maynot be required to achieve the desired result. Single-agent therapy would clearly reduce costs, and possible complications, of therapy. Secondly, Boumpas et alZ9reported complete responses in each of seven refractory patients with SLE-associated immune thrombocytopenia treated with one to four doses of REINER, GERNSHEIMER, AND SLICHTER cyclophosphamide at 0.75 to 1.0 g/m2.Four of these patients had sustained responses with a mean followup of 5.6 years. Thus, single-agent pulse cyclophosphamide appears tobe beneficial in bothprimary and SLE-associated AITP. Finally, Weinerman et alZhreported responses in eight of 14 patients with immune thrombocytopenia treated with varying schedules of intermittent cyclophosphamide in doses ranging from 300 to 600 mg/m’. These patients had previously failed corticosteroids and, in some cases, splenectomy. Four of the responders had disseminated SLE. Six of the responses were sustained with followup ranging between 15 and 20 months. The slightly lower response rate in this earlier report may be due to the lower dose of pulse cyclophosphamide compared with our study andthose of Figueroa et a]’’ and Boumpas et a12’ The mechanism of action of pulse cyclophosphamide in autoimmune disorders appears to be suppression of both T and B lymphocyte numbers and function,” which leads to diminished autoantibody p r ~ d u c t i o n .In ~ ~previous ,~~ studies of AITP patients treated with cyclophosphamide or cyclophosphamide-based combination chemotherapy, clinical response was associated with reduction of platelet antibody level~.~’~’’ In our series, postcyclophosphamide platelet antibody studies were performed in only three patients; two of the three patients showed disappearance of platelet autoantibody following a complete, persistent response to pulse cyclophosphamide. In one patient (no. l ) , platelet autoantibody disappeared within 4 weeks of treatment. The other (no. 5) had a more gradual decline in antibody level over a period of several years. The third patient (no. 16) had persistent platelet autoantibody 2 months after treatment that resulted in a transient CR, but followup platelet antibody testing was not performed. Several patient characteristics were examined for an association with pulsecyclophosphamide treatment outcome. Because of the small number of patients studied, none of the associations reached statistical significance. Of those examined, shorter disease duration was most strongly associated with response to pulse cyclophosphamide (P value = .IO), and patient age, sex, and phase of disease were all marginally significant as well. The association of shorter disease duration has beennoted for AITP response to oral low-dose cyclophosphamide as Splenectomized patients have also been reported to have a better response rate to oral cyclophosphamide,33but we are unable to confirm this association with pulse cyclophosphamide because ail but one of our patients had undergone splenectomy. Acute side-effects occurred during six of 27 (22%) of the pulse cyclophosphamide treatment courses. Neutropenia occurred in three patients, but was severe in only one patient in whom staphylococcal sepsis developed. The occurrence of deep venous thrombosis in two patients was associated with a rapid and complete response to pulse cyclophosphamide.Although cyclophosphamide itself is not associated with hypercoaguability, it is possible that the rapid increase in platelet count may have induced a transient hypercoaguable state due to the presence of circulating, immature hyperfunctional platelets that are thought to circulate in AITP patients.34 However, the acute increase in platelet count From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on December 29, 2014. For personal use only. PULSE CYCLOPHOSPHAMIDE FOR AITP sometimes seen postsplenectomy for this and other disorders is not commonly associated with deep venous thrombosis unless other intrinsic abnormalities of the blood are present and associated with abnormal platelet function such as myeloproliferative disorders.35336 Other known side-effects of cyclophosphamide such as nausea, vomiting, alopecia, and hemorrhagic cystitis were not noted in this series. Although no long-term side-effects of pulse cyclophosphamide were noted in our patients, an association between cyclophosphamide and secondary cancers has been wellestablished. In patients with rheumatologic disorders treated with oral cyclophosphamide, the risk appears to be related to cumulative cyclophosphamide dose and duration of thera ~ y . Krause3* ~’ reported three patients with AITP who developed acute myeloid leukemia 2 to 4 years after receiving low-dose oral cyclophosphamide. An increased risk of secondary malignancy has also been noted in patients treated with pulse cyclophosphamide for primary neoplasms3’ and as a conditioning regimen preceding bone marrow transplantation for aplastic anemia.@The incidence of secondary cancers in patients with autoimmune disease treatedwith pulse cyclophosphamide is unknown, but appears to be lower than with continuous oral cycloph~sphamide.~~ To date, there have been five cases reported of malignancy complicating pulse cyclophosphamide in SLE patient^.^'^^'.^' Another potential complication of pulse cyclophosphamide is sterility, although this side-effect is also less common than with continuous low-dose cyclophosphamide therapy. Nevertheless, infertility has been reported in over half of the women receiving pulse cycloph~sphamide.~~ The role of pulse cyclophosphamide in the treatment of refractory AITP requires careful consideration of the relative benefits and risks. Our data suggest that pulse cyclophosphamide is an effective treatment for refractory AITP and should be strongly considered in severely-affected patients who do not respond to standard therapy. It may be particularly efficacious in elderly patients in whom the long-term risks of malignancy and sterility are less of a concern than in younger patients, as well as in patients for whom splenectomy is a high-risk procedure. Nevertheless, given the relatively high mortality rate of refractory AITP, treatment at any age may be justified. The optimum dose and treatment schedule of pulse cyclophosphamide remain to be determined. REFERENCES 1 . Mueller-Eckhardt C: Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Clinical and immunologic considerations. Semin Thromb Hemost 3:125, 1977 2. McMillan R: Chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 304:1135, 1981 3. Kelton JG, Gibbons S: Autoimmune platelet destruction: Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Semin Thromb Hemost 8:83,1982 4. Karpatkin S: Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. Semin Hematol 22:260, 1985 5. Bussel JB: Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 4:179, 1990 6. Guthrie TH Jr, Brannan DP, Prisant LM: Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in the older adult patient. Am J Med Sci 296:17, 1988 7. Cortelazzo S, Finazzi G, Buelli M, Molteni A, Viero P, Barbui 357 T: High risk of Severe bleeding in aged patients with chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 77:31, 1 9 9 1 8. McMillan R: Antigen-specific assays in immune thrombocytopenia. Transfus Med Rev 4:136, 1990 9. Kunicki TJ, Newman PJ: The molecular immunology of human platelet proteins. Blood 80:1386, 1992 10. Aster R H , Keene W R : Sites of platelet destruction in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol 16:61, 1969 11. McMillan R, Longmire R L , Tavassoli M: In vitro platelet phagocytosis by splenic leukocytes in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 290249, 1974 12. Ballem PJ, Segal GM, Stratton JR, Gernsheimer T, Adamson JW, Slichter SJ: Mechanisms of thrombocytopenia in chronic autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. J Clin Invest 8033, 1987 13. Gernsheimer T, Stratton J, Ballem PJ, Slichter SJ:Mechanisms of response to treatment in autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 320974, 1989 14. Siege1RS, Rae JL, Barth S, Coleman RE, Reba RC, Kurlander R, Rosse WF: Platelet survival and turnover: Important factors in predicting response to splenectomy in immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Hematol 30:206, 1989 15. Baldini M: Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 274:1245, 1966 16. Berchtold P, McMillan R: Therapy of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in adults. Blood 74:2309, 1989 17. Facon T, Caulier MT, Fenaux P, Wibaut B, Cappelaere A, Quiquandon I, Bauters F Interferon alpha-2b in refractory adult chronic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol 78:464, 1991 Geary CG: Idiopathic thrombocyto18. Kelsey PR, Schofield W, penic purpura treated with cyclosporine. Br J Haematol60: 197, 1985 19. Bussel JG, Pham LC, Aledort L, Nachman R: Maintenance treatment of adults with chronic refractory immune thrombocytopenic purpura using intravenous infusions of gammaglobulin. Blood 72:121, 1988 20. Brox AG, Howson-Jan K,Fauser AA. Treatment of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura with ascorbate. Br J Haematol 70:341, 1988 21. Snyder HW Jr. Cochran SK, Balint JP Jr, Bertram JH, Mittelman A, Guthrie TH Jr, Jones FR: Experience with protein A-immunoadsorption in treatment-resistant adult immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 79:2237, 1992 22. Clarkson SB, Bussel JB, Kimberly RP, Valinsky JE, Nachman RL, Unkeless JC: Treatment of refractory immune thrombocytopenic purpura with an anti-Fc-receptor antibody. N Engl J Med 314:1236, 1986 23. Figueroa M, Gehlsen J, Hammond D, Ondreyco S, Piro L, Pomeroy T, Williams F, McMillan R: Combination chemotherapy in refractory immune thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 328:1226, 1993 24. Austin HA 111, Klippel JH, Balow JE, Le Riche NGH, Steinberg AD, Plotz PH, Decker JL: Therapy of lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med 314:614, 1986 25. McCune WJ, Bolbus J, Zeldes W, Bohlke P, Dunne R, Fox DA: Clinical and immunologic effects of monthly administration of intravenous cyclophosphamide in severe systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 318:1423, 1988 26. Weineman B, Maxwell W ,Hryniuk W: Intermittent cyclophosphamide treatment of autoimmune thrombocytopenia. Can Med Assoc J 111:1100, 1974 Fate of therapy failures 27. Picozzi VJ, Roeske WR, Greger W: in adult idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med 69:690, 1980 28. Pizzuto J, Ambriz R: Therapeutic experience in 934 adults with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: Multicentric trial of the From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on December 29, 2014. For personal use only. 358 cooperative Latin American group on hemostasis and thrombosis. Blood 64: 1179, 1984 29. Boumpas DT, Bares S, IQ11 JH, Balow JE: Intermittent cyclophosphamide for the treatment of autoimmune thrombocytopenia in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med 112:674, 1990 30. McCune WJ, Fox J: Intravenous cyclophosphamide therapy of severe SLE. Rheum Dis 15:455, 1989 3 1. Fujisawa K, Tani P, Piro L, McMillan R: The effect of therapy on platelet-associated autoantibody in chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 81:2872, 1993 32. Verlin M, Laros RK, Penner JA: Treatment of refractory thrombocytopenic purpura with cyclophosphamide. Am J Hematol 1:97, 1976 33. Finch SC, Castro 0, Cooper M, Covey W, Erichson R, McPhedran P: Immunosuppresive therapy of chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Med 56:4, 1974 34. Karpatkin S: Heterogeneity of human platelets 11. Functional evidence suggestive of young andold platelets. J Clin Invest 48:1083, 1969 35. Rattner DW, Ellman L, Warshaw AL: Portal vein thrombosis after elective splenectomy. Arch Surg 128:565, 1993 36.RandiML, Fabris F, Dona S, Girolami A: Evaluation of platelet function in postsplenectomy thrombocytosis. Folia Haematologica 114:252, 1987 37. Baker GL, Kahl LE, Zee BC, Stolzer BL, Aganval AK, REINER, GERNSHEIMER, AND SLlCHTER Medsger TA: Malignancy following treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with cyclophosphamide. Am J Med 83:1, 1987 38. Krause JR: Chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: Development of acute non-lymphocytic leukemia subsequent to treatment with cyclophosphamide. Med Pediatr Oncol 10:61, 1982 39. Kaldor JM, Day NE, Pettersson F, Clarke A, PedersenD, Mehnert W, Bell J, Host H, Prior P, Karjalainen S, Neal F, Koch M, Band P, Choi W, Pompe Kim V, Arslan A, Zaren B, Belch AR, Storm H, Kittelmann B, Fraser P, Stovall M: Leukemia following chemotherapy for ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 322: 1, 1990 40. Witherspoon RP, Storb R, Pepe M, Longton G, Sullivan KM: Cumulative incidence of secondary solid malignant tumors in aplastic anemia patients given marrow grafts after conditioning with chemotherapy alone. Blood 79:289, 1992 41. Gibbons RB, Westerman E: Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia following short-term, intermittent, intravenous cyclophosphamide treatment of lupus nephritis. Arthritis Rheum 3 1:1552, 1988 42. Vasquez S, Kavanaugh AF, Schneider NR, Wacholtz MC, Lipsky PE: Acute non-lymphocytic leukemia after treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus with immunosuppressive agents. J Rheumatol 19:1625, 1992 43. Balow JE, AustinHA 111, Tsokos GC, Antonovych TT, Steinberg AD, Klippel JH: Lupus nephritis. Ann Intern Med 106:79, 1987 From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on December 29, 2014. For personal use only. 1995 85: 351-358 Pulse cyclophosphamide therapy for refractory autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura [see comments] A Reiner, T Gernsheimer and SJ Slichter Updated information and services can be found at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/85/2/351.full.html Articles on similar topics can be found in the following Blood collections Information about reproducing this article in parts or in its entirety may be found online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#repub_requests Information about ordering reprints may be found online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#reprints Information about subscriptions and ASH membership may be found online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/subscriptions/index.xhtml Blood (print ISSN 0006-4971, online ISSN 1528-0020), is published weekly by the American Society of Hematology, 2021 L St, NW, Suite 900, Washington DC 20036. Copyright 2011 by The American Society of Hematology; all rights reserved.

© Copyright 2026