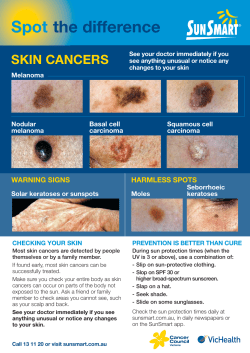

2008 Canadian Cancer Statistics Questions about Cancer? 1888 939-3333