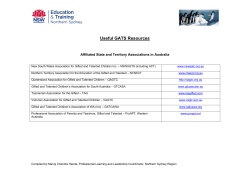

Highly & Profoundly Gifted Serving learners Winter 2009 Vol. 40 no. 4 $12.00