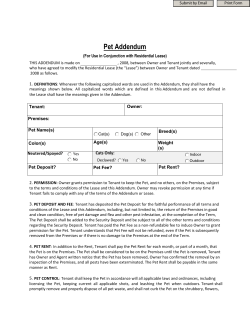

Document 71144