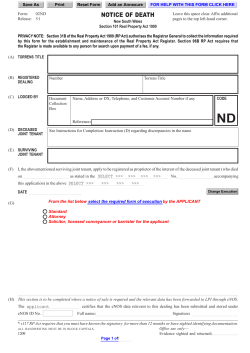

Document 71719