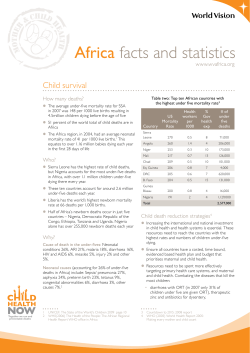

Child Survival THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2008