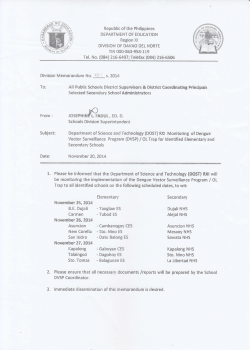

One Chance to get it right