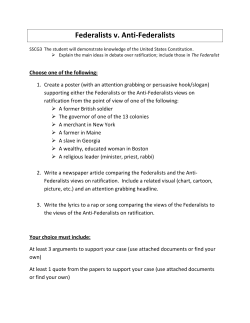

Is There Something Like a Constitution of International Law? A