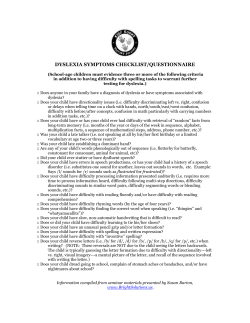

Dyslexia and Multilingualism: Identifying and risk of developing SpLD/dyslexia.