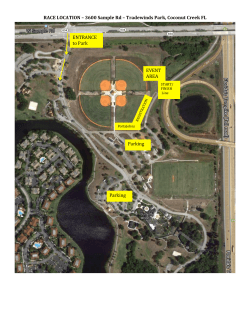

Parking - Cheshire East Council