CENTRAL POLICY UNIT THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HONG

CENTRAL POLICY UNIT

THE GOVERNMENT OF THE HONG KONG

SPECIAL ADMINISTRATIVE REGION

SOCIAL ATTITUDES OF THE YOUTH

POPULATION IN HONG KONG:

A FOLLOW-UP STUDY

THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY OF HONG KONG

MARCH 2015

Social Attitudes of the Youth Population in

Hong Kong : A Follow-up Study

《香港年青人的社會態度 — 跟進研究》

Final Report

Submitted by

Public Policy Research Centre

Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

March 2015

Table of Contents

Preface

i

Executive Summary

1

摘 要

15

I. Background of the Study

1

II. Methodology

2

III. Telephone Survey on Social Attitudes of the Youth Population in

Kong: May to June 2014

Hong

4

3.1 Demographic Characteristics

4

3.2 Civic Engagement and Political Information Seeking

5

3.3 Voting Behaviour in the Legislative Council in 2012

8

3.4 Life Satisfaction

9

3.5 Identity and Political Trust

12

3.6 Attitudes Towards Education and Employment in the Mainland

13

3.7 To What Extent Youth Perceive Opportunities

15

3.8 Attitudes Towards "Occupy Central" and Civil Referendum

17

3.9 Conflicts between the Government and Civil Society

20

3.10 Defending for Autonomous Hong Kong Administration

22

IV. Correlates of Dissent Youth in Hong Kong

25

4.1 Social Attitudes of Dissent

25

4.2 Aggregate Measure of Dissenting Attitudes

27

4.3 Demographic Profile of the Strong Dissidents

32

4.4 Other Correlates of Dissenting Attitudes

34

4.5 Political Trust, Identity and Dissenting Attitudes

36

4.6 Materialism, Postmaterialism and Social Attitudes

38

4.7 Predictors of Dissenting Social Attitudes

45

V. Conclusion

51

References

58

Appendix 1

1

List of Tables

Table 3.1 Demographic Characteristics

5

Table 3.2 How often participating in Demonstrations or Rallies since 1997?

6

Table 3.3 Awareness of Demonstrations or Rallies to be Organized

6

Table 3.4 Channels for Learning About Demonstrations or Rallies to be Organized

(multiple responses allowed)

7

Table 3.5 How Users of Electronic Communications Learn about Demonstration or

Rallies to be Organized (multiple responses allowed)

8

Table 3.6 Voted in LegCo Election in 2012? (Eligible voters only)

9

Table 3.7 Which Political Camp They Cast Their Vote for in the LegCo Election in

2012 (only those having voted)

9

Table 3.8 Satisfaction with Political development in HK

10

Table 3.9 Satisfaction with Environmental conservation in HK

10

Table 3.10 Satisfaction with Economic development in HK

11

Table 3.11 Overall Life Satisfaction

11

Table 3.12 Identity and Political Trust

13

Table 3.13 Attitudes towards Pursuing Further Studies in the Mainland

14

Table 3.14 Attitudes towards Taking Up Employment in the Mainland

14

Table 3.15 Perception of Opportunities Available to Same Age Cohort for Personal

Development in Hong Kong

15

Table 3.16 Comparing with the present, will opportunities for personal development

in Hong Kong become better or worse in future?

16

Table 3.17 Generally speaking, are you satisfied with the opportunities for your own

development in Hong Kong?

17

Table 3.18 Support "Occupy Central" for Genuine Universal Suffrage in 2017 Chief

Executive Election

18

Table 3.19 Popular Nomination of Chief Executive Candidates in 2017 is

Indispensable

19

Table 3.20 Would Vote in "6.22 Civil Referendum" Organized by "Occupy Central" in

June 2014?

19

Table 3.21 Conflicts between Government and Civil Groups over Land Development

Issues

20

Table 3.22 Political Party Most Supported

21

Table 3.23 Democratic Progress since 1997

22

Table 3.24 Hong Kong Interests Prevail when Conflict between China and Hong

Kong

23

Table 3.25 One-way Permit Scheme for Mainland Residents to Hong Kong Approved

by Hong Kong Government

24

Table 3.26 Quota for Individual Visit Scheme for Mainland Residents must be

Limited

24

Table 4.1 Percentage of Respondents with Dissenting Attitudes: A Summary

29

Table 4.2 Aggregate Dissent Score & Dissent Intensity

29

Table 4.3 Demographic Characteristics and Dissenting Attitudes

32

Table 4.4 Demographic Characteristics of Youth Population who Show Strong

Dissent

32

Table 4.5 Correlations between Development Opportunities and Dissenting Attitudes

35

Table 4.6 Correlations between Quality of Life and Dissenting Attitudes

36

Table 4.7 Political Trust and Dissenting Attitudes

37

Table 4.8 Identity and Dissenting Attitudes

38

Table 4.9 Mean Scores of Postmaterialist and Materialist Value Orientations

43

Table 4.10 Postmaterialist Value Orientation & Social Attitudes

44

Table 4.11 Relative Strength of Predictors on Aggregate Dissent Score

48

Table 4.12 Relative Strength of Predictors on Aggregate Dissent Score in 2014

49

Preface

Background and Objective of the Study

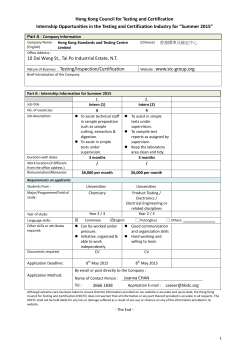

This study was commissioned by the Central Policy Unit (CPU) of the

Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region in May

2014. It is a follow-up to a 2010 research also commissioned by CPU.

The objective of the study is to follow-up on the key findings of the 2010

survey, focusing on six general questions:

(1) Does the younger generation have unique socio-political orientations

vis-à-vis the older cohort? Are there any distinctive diversity in

values and orientation within this generation?

(2) How does the younger generation perceive their own position and

opportunities in the socio-economic system, and in particular the

chances of improving their social and economic conditions?

(3) More specifically, does the younger generation exhibit a distinctive

kind of post-materialist and "localistic" values?

(4) What are the socio-demographic and biographical factors that could

account for diversities in socio-political orientations among the

younger generation?

Methodology

This study uses a quantitative approach to gather information on the

i

young population of Hong Kong, including the social attitudes, beliefs,

values, orientations and behaviors. A telephone survey was conducted

from 14 May to 24 June 2014.

The main age cohort under study

includes those born in the years between 1975 and 1999, that is, those

aged 15 to 39 as of the year 2014. In which the 30-39 cohort are

included as a reference group to compare with the younger population.

Research Team

Members in the research team of the Public Policy Research Centre,

Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, the Chinese University of

Hong Kong include:

Stephen Wing-Kai Chiu, Professor, Department of Sociology; and

Co-Director, Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies

Leung Yee-kong, Research Associate, Public Policy Research Centre,

Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies

ii

Executive Summary

1. Background of the Study

This is a follow-up project to a 2010 research commissioned by the

Central Policy Unit.

The idea is to gauge to what extent social and

political attitudes of young people in Hong Kong have changed over the

past several years and the reasons behind.

We have witnessed an

apparent escalation of social and political participation outside of

institutionalized channels over the past years.

The findings of this

project should provide us with insights to examine a number of prevalent

explanations of the rise in youth activism.

2. Methodology

A telephone survey was conducted from 14 May to 24 June 2014 by the

Telephone Laboratory of the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies

at The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The main age cohort under

study includes those born in the years between 1975 and 1999, that is,

those aged 15 to 39 as of the year 2014.

In which the 30-39 cohort are

included as a reference group to compare with the younger population.

A total of 2,000 respondents who completed the survey were drawn from

the target population.

S-1

3. Telephone Survey on Social Attitudes of the Youth Population

in Hong Kong 2014

3.1 Demographic Characteristics

Of the total of 2,000 respondents who completed the survey, 1,076

(53.8%) are female and 924 (46.2%) male.

By generational distribution, 362 (18.1%) are aged 15-17, 276 (13.8%)

aged 18-19 (in combination, 638 or 31.9% aged 15-19), 780 (39.0%)

aged 20-29, and 582 (29.1%) aged 30-39.

By educational attainment, 7.7% are junior secondary or below, 39.0%

senior secondary, and 53.3% tertiary education or above.

A majority of the respondents (77.1%) were born in Hong Kong.

Of

those not born in Hong Kong, 8.3% have lived here less than 7 years,

40.4% between 7 and 15 years, and the remaining 51.3% 15 years or

more.

Only 12.2% of respondents have experience of living, education,

or working overseas.

The median household monthly income category is $30,000-$49,999.

Classified by economic activity status, 47.0% are economically active,

42.8% students, and 10.1% economically inactive.

3.2 Civic Engagement and Political Information Seeking

Anti-establishment sentiment is reflected in actions of our respondents.

Half of respondents (50.2%) have not joined any demonstration or rally

S-2

since 1997, and a mere 3.2% report having joined frequently. A visible

group of youth population (46.6%) has experience in civic actions either

occasionally or frequently.

The Internet (74.3%) outplays conventional mass media to become the

major channel to receive information on civic actions to be organized.

TV comes not close enough (60.2%) and printed newspapers are farther

apart (48.3%).

3.3 Voting Behaviour in the Legislative Council in 2012

A majority of respondents reported voting for candidates from the

Pan-democrats camp, and about 26% of them did not remember to whom

they cast their vote.

3.4 Life Satisfaction

The majority of all age groups have indicated dissatisfaction with two

conditions: political development and environmental conservation. And

the economical development is rated average by half of respondents in all

age groups.

The differences among age groups are statistically

significant in three issues, but the trends are the same among age groups.

Respondents are generally positive towards overall quality of life.

The

15-19 age group is relatively more satisfied with overall life than the

other two cohorts.

The differences among cohorts are statistically

significant, but the magnitude is not large.

All respondents are on

average slightly satisfied with their personal life.

S-3

3.5 Identity and Political Trust

An overwhelming majority of the two younger cohorts (15-19, and 20-29)

identify themselves as Hong Kongers, both over 80%, in contrast to 10%

being Chinese.

The older 30-39 cohort has about 63% of Hong Kong

identification, and about 21% being Chinese.

More respondents have trust in the Hong Kong SAR Government (42.6%)

than in the Central Government (25.2%).

The middle cohort (20-29)

has the least trust in both governments (34.6% Hong Kong, 18.8%

Central).

The youngest (15-19) has the most trust in Hong Kong

government (48.2%), and the oldest (30-39) the most trust in Central

government (36.1%).

3.6 Attitudes Towards Education and Employment in the Mainland

Respondents generally welcome opportunities to study or work in the

Mainland.

More than 40% of respondents find it acceptable to pursue

further study in the Mainland.

The percentage is similar across cohorts.

About 50% of respondents would be willing to work in the Mainland,

and the percentage is about the same across cohorts.

Our respondents

are rejecting Chinese identity only at an ideological level.

When it

comes to personal life and development, however, the youth population

finds it acceptable to have connections with the Mainland, e.g. through

further studies and employment opportunities.

3.7 To What Extent Youth Perceive Opportunities

About 50% of all respondents perceive moderate amount of opportunities

S-4

available.

Slightly more than 30% perceive limited or no opportunity

available for their personal development.

Respondents of aged 20-29

are the least positive to the opportunities available to them.

Referring to their perception of opportunities for personal development in

future, nearly 40% of respondents expect their future would be the same

as now.

The youngest are the least pessimistic about their future than

others, 14.1% expecting a better tomorrow, or 46.9% worse than now.

The middle cohort (aged 20-29) is the least positive, with half of them

(51.2%) expecting a worse tomorrow.

About a quarter of all respondents are dissatisfied with the opportunities

available for their own development in Hong Kong.

Satisfied

respondents (24.3%) are about the same as those dissatisfied (23.5%).

Comparatively speaking, the youngest (aged 15-19) is the least satisfied

generation (19.2%), and the oldest (30-39) the most satisfied (29.9%).

3.8 Attitudes Towards "Occupy Central" and Civil Referendum

The younger two cohorts (aged 15-19 and 20-29) have more than half

supporting the "Occupy Central" movement to fight for their ideal form

of universal suffrage in 2017 Chief Executive Election.

The oldest

cohort (30-39) is ambivalent with favourable (46.7%) and unfavourable

(46.4%) responses about the same.

The popular nomination receives overwhelming support from all age

cohorts.

The younger two cohorts have 80% or more, and the oldest

about 70% endorsement of popular nomination.

At most time of the

survey period, the Civil Referendum had not yet taken place.

S-5

Respondents, however, were not very enthusiastic to vote in the Civil

Referendum.

Only one-third in each cohort would cast a vote.

3.9 Conflicts between the Government and Civil Society

The conflicts between the administration and civil groups on

environmental conservation and land development are commonly seen.

The most supportive to the government is from the oldest cohort with

19.5%.

The younger two cohorts have less than 10%.

Among named parties, the Democratic Party is the most identified with

(6.1%).

Although Scholarism has the lowest percentage to be named

among the pan-democratic camp, it is the third most popular in the 15-19

cohort.

For the pro-establishment camp, the most supportive is the

30-39 cohort with 10.5%, while less than 5% from the two younger

cohorts.

The youth population is not satisfied with the democratic progress in

Hong Kong since 1997. More than half find the progress too slow.

Interestingly, the youngest is the least (still 46.4%) feeling too slow the

democratic progress, and the aged 20-29 the most (62.6%).

3.10 Defending for Autonomous Hong Kong Administration

About 90% of respondents insist that the interests of Hong Kong must

prevail whenever conflicts between Hong Kong and China occur in Hong

Kong.

About 80% of respondents in favour of autonomous

administration of Hong Kong, as reflected by the approval of One-way

Permit Scheme and imposing quota for Individual Visit Scheme for the

S-6

Mainland residents.

4. Correlates of Dissent Youth in Hong Kong

4.1 Social Attitudes of Dissent

To examine the perceptions and attitudes of socially discontented youth,

9 social attitudes grouped in 4 areas are measured.

4.1.1 Attitudes Towards "Occupy Central" and Civil Referendum

(1) support Occupy Central for genuine universal suffrage:

the younger two cohorts (aged 15-19 and 20-29) have more

than half supporting the ideal form of universal suffrage in 2017

Chief Executive Election;

(2) agree Popular Nomination for Chief Executive election in 2017:

all

age

cohorts

overwhelmingly

support

the

popular

nomination;

(3) whether or not would vote in 22 June 2014 civil referendum:

one-third of eligible respondents (i.e. age 18 or above) in each

cohort would cast a vote.

4.1.2 Conflicts between the Government and Civil Society

(4) conflicts between the HKSAR Government and concern groups

on land development issues:

the most supportive to the government is from the oldest cohort

with 19.5%, and the younger two cohorts have less than 10%.

S-7

4.1.3 Political identification

(5) support pan-democratic political camp in Hong Kong:

Democratic Party is the mostly supported (6.1%); Scholarism

the lowest percentage named among the pan-democratic camp,

but the third most popular in the 15-19 cohort;

to the pro-establishment camp, the most supportive is the 30-39

cohort with 10.5%, while less than 5% from the two younger

cohorts;

(6) evaluation of democratic progress in Hong Kong since 1997:

the youth population is not satisfied with the democratic

progress in Hong Kong since 1997. More than half find the

progress too slow.

4.1.4 Defending for Autonomous Hong Kong Administration

(7) agree Hong Kong interests take priority when China & Hong

Kong in conflict:

near 90% of respondents insist that the interests of Hong Kong

must prevail;

(8) Hong Kong SAR Government must have approval right of

One-way Permit:

about 80% of respondents in each cohort are in favour of Hong

Kong having approval right;

(9) agree Hong Kong to restrict visitors via Individual Visit Scheme:

again about 80% of respondents in each cohort support

imposing quota for Individual Visit Scheme.

4.2 Aggregate Measure of Dissenting Attitudes

The "aggregate" level of dissent is measured by counting how many of

S-8

the above 9 social attitudes expressed discontent by the youth population.

The measure of "aggregate dissent" has a range of values from 0 to 9, the

higher the score, the more discontented a respondent is.

Except the

popular nomination for Chief Executive election in 2017, the respondents

in the 20 to 29 age cohort are the most dissenting comparing to other two

cohorts.

Almost no respondent is completely contented (i.e., score 0), 67.2% of

thee respondents are a little or moderately dissenting (with scores from 1

to 6). About 32% of respondents are reported to be holding strong

dissenting attitudes (scores 7 to 9).

The "baseline" 30-39 cohort is the least discontented, with the lowest

mean score of dissent 5.0; about 3% of them do not show any discontent

(with zero dissent score.)

The youngest generation (age 15-19) is as much (or as less) discontented

as the oldest, with mean score of dissent 5.1. No one in the youngest

generation reports zero score.

The middle generation (20-29) has the

highest dissent score of 5.8.

A tiny proportion (0.6%) of the middle

generation reports zero dissent.

The 20-29 cohort has the largest proportion to show strong dissent.

About 40% of them possess dissent score from 7 to 9.

The youngest

and the oldest cohort have more or less the same proportion of strong

dissent, with 21.8% and 19.4% respectively.

There are some statistically significant differences in dissent scores by

S-9

demographic

characteristics.

In

general,

the

more

dissenting

respondents are male, born in Hong Kong, tertiary educated, and in more

economically well-off household. Overseas living experience has no

statistically association with the aggregate dissent measure.

For those

statistically significant differences, the magnitude is mostly less than 1

(out of 9).

The most divided demographic subgroups are those tertiary

educated against those junior secondary or below, and the difference is

said to be as "large" as 1 social issue apart.

Demographically speaking,

the overall youth population is not hugely divided.

4.3 Demographic Profile of the Strong Dissidents

A notable minority of 31.6% of respondents are identified as having

strong dissent, with dissent scores between 7 and 9.

Who are the

strongly dissenting respondents?

The strong dissidents share similar demographic characteristics

regardless of their generation.

The profile analysis reveals that the

youth population holding strong dissenting attitudes share similar

demographic characteristics: tertiary educated (68.1%), born in Hong

Kong (82.6%), not at the bottom layer economically (median household

monthly income $30,000-49,999), but only a few having experience

living overseas (11.7%).

4.4 Other Correlates of Dissenting Attitudes

The 3 measures of self-perceived opportunities available for personal

development are found to be negatively correlated with the dissenting

S-10

attitudes of respondents.

The more dissenting the respondents are, the

fewer the opportunities they perceive as available to them.

The

relationships (or predictive power) are statistically significant but very

weak.

In other words, respondents perceiving limited opportunities are

not visibly more dissenting than those perceiving better development

opportunities.

Our findings cannot conclude that perceptions of blocked

mobility reinforce dissenting attitudes.

The effects of life satisfaction and happiness on dissenting attitudes are

almost invisible, with statistically significant but very weak negative

correlations.

Respondents dissatisfied with their life or feeling unhappy

do not generate noticeably more dissenting attitudes than their more

satisfied or happy counterparts.

Health condition has not been found

statistically significant difference.

The findings do not support

anecdotal explanation that dissatisfaction with life leads to dissent.

4.5 Political Trust, Identity and Dissenting Attitudes

A wide split among political trusts and dissenting attitudes.

In 2014,

those who do not trust in Hong Kong Government express stronger

dissent (by 2 more social issues apart out of 9) than those who trust.

And the gap is about the same between those who trust in Central

Government and those who do not.

Those who trust in Central

Government have the least dissent, and the score is lower than those who

trust in Hong Kong Government.

Those who identify themselves as Hong Kongers have the strongest

dissent (score 5.8), and who consider themselves Chinese is the least

dissent (3.8).

The gap between the two identities is as large as 2 social

S-11

issues apart.

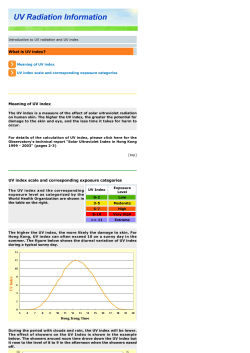

4.6 Materialism, Postmaterialism and Social Attitudes

The influences of value orientations on social and political perceptions

are real and significant.

One prominent approach to explaining such

influences is the cultural shift from materialism to postmaterialism which

has triggered a series of research studies in western societies since the

1970s.

Previous local studies clearly reveal that Hong Kong people were

basically materialist while also possessing partial but not yet fully

developed postmaterialist values.

In 2014 survey, the youth population is equally postmaterialistic and

materialistic.

For individual items measuring postmaterialist or

materialist values, the highest evaluated is "maintaining order in Hong

Kong" (asked in Chinese: 維持治安) classified as materialist value.

The second highest is "protecting freedom of speech" (asked in Chinese:

保障言論自由) from postmaterialist value.

And the remaining items

score come from postmaterialist and materialist value orientation

alternatively in order of magnitude.

This peculiar order further

illustrates the coexistence of both value orientations among the youth.

Their inclination towards which value orientation is then not about what

they hold more, but probably when and on what basis they prefer one to

another.

Postmaterialist value orientation has significant effects on social attitudes

S-12

of dissent in 2014.

The magnitude of the difference found in each

attitude is notable between the dissent and the conservative.

The

general pattern is that higher postmaterialist score results in more critical

perception of socio-political issues, i.e. expressing dissenting attitudes.

The

postmaterialist

value

orientation

significantly

differentiates

evaluation of socio-political issues.

4.7 Predictors of Dissenting Social Attitudes

To better gauge the combined effects of both demographic (structural) as

well as value orientations predictors on dissenting attitudes, multivariate

regression analysis is employed to test their relative effects on dissent

score.

In the multivariate model, the effects of almost all demographic variables

become statistically insignificant.

effect in predicting dissent.

Generational effect has no significant

The common belief that (young) age

accounts for dissenting attitudes is not supported in this vigorous

statistical analysis.

Postmaterialist value orientation has the relatively

strongest effect in predicting aggregate dissent score.

The regression model illustrates that personal attributes are not able to

account for dissenting social attitudes.

Value orientations are more

powerful predictors in this regard.

S-13

5. Conclusion

The 2014 survey was taken from 14 May to 24 June 2014.

This means

that data collection was done during a period of "normal" social

atmosphere.

By "normal" we refer to usual social and political

atmosphere we have been experiencing in most of our lifetime, but not

incidentally mobilized scenarios. In this regard, respondents were not

motivated nor mobilized by many political conflicts seen on streets from

September 2014 onwards.

Their evaluation towards socio-political

issues was believed to be reflecting their "normal" perceptions, and

extreme political split was therefore not expected.

In terms of academic and practical values, the survey was able to be

conducted during the period of "normal" social conditions. In order to

track long term changes in social and political sentiments, research

during "normal" period is necessary.

S-14

摘要

1. 研究背景

本研究是為跟進 2010 年一項關於年青人的社會態度調查而進行,當

時同樣由香港區政府中央政策組撥款資助。2014 年再次進行研究是

希望探討自 2010 年調查完成之後,四年來香港年青人對社會及政治

議題的態度有甚麼變化。事實上自 2010 年起,不少社會及政治動員

事件都是在既有政治制度外發生,當中有不少年青人參加。因此,本

跟進研究讓我們了解年青人在社會及政治參與方面更趨熱衷及激烈

的種種促成因素。

2. 研究方法

是次研究通過電話調查收集被訪者意見,調查日期是 2014 年 5 月 14

日至 6 月 24 日,由香港中文大學香港亞太研究所電話調查室負責。

訪問對象是 2014 年 15 至 39 歲的香港年青人,即是生於 1975 至 1999

年之間,當中 30 至 39 歲是本研究的基線,以對比 15 至 29 歲較年青

的一群。最終成功訪問 2,000 人。

S-15

3. 2014 年 5 月至 6 月進行之電話調查分析結果

3.1 受訪者人口特徵

成功訪問了 2,000 名於 1975 至 1999 年間出生的香港市民,女性 1,076

名(53.8%),男性 924 名 (46.2%)。

三個年齡組別的分佈是:362 名 (18.1%) 15 至 17 歲,276 名 (13.8%)

18 至 19 歲(15 至 19 歲合計 638 名,佔 31.9%)

,780 名 (39.0%) 20

至 29 歲,及 582 名 (29.1%) 30 至 39 歲。

教育程度方面,7.7% 初中或以下,39.0% 高中,53.3%大專或以上

程度。

大部份受訪者 (77.1%) 都是生於香港。並非在香港出生的人當中,

8.3% 港少於 7 年, 40.4% 居住了 7 至 15 年,51.3% 居住 15 年或

以上。只有 12.2% 受訪者有海外居住、求學或工作經驗。

受訪者家庭每月收入中位數是港幣 30,000 至 49,999 元。47.0% 受訪

者從事經濟活動, 42.8% 是學生,10.1% 沒有從事經濟活動。

3.2 公民參與和獲取政治訊息

約半數受訪者 (50.2%) 自 1997 年沒有參加過任何示威或遊行,而只

有 3.2%回答常常參加,其餘 46.6% 間中參加公民行動。

S-16

有 74.3%受訪者經互聯網獲取公民行動資訊,取代傳統大眾媒體成為

最主要途徑,有 60.2%通過電視得知,印刷報章則有 48.3%。

3.3 2012 年立法會選舉投票情況

大部份有投票的受訪者於 2012 年立法會選舉中,都投票支持泛民主

派候選人,而大約 26%有投票者忘記投票給那個候選人。

3.4 生活滿意度

不同年齡的受訪者都不滿意於香港的政治和環境保育情況,而各年齡

組分別都有近一半人對經濟情況只是感覺一般。不同年齡組別之間的

生活滿意度在統計學上有顯著分別,但是方向大致相同。

另一方面,受訪者普遍傾向滿意他們的生活質素,15 至 19 歲一群比

其他兩個年齡組更感滿意。不同年齡組別之間,雖然生活滿意度在統

計學上有顯著分別,實際上差異只是微不足道。

3.5 身份與政治認同

較年青的兩個年齡組別 (15 至 19 及 20 至 29 歲) 之中超過 80%受訪

者都選擇認同自己是

「香港人」

,只有 10%選擇認同自己是

「中國人」

。

30 至 39 歲則有 63% 認同自己是「香港人」

,21%則選擇「中國人」。

S-17

政治認同方面,信任香港特區政府的受訪者比例 (42.6%) 高於信任

中央政府 (25.2%),而世代之間亦見差異。中間年齡組 (20 至 29 歲)

對政府的信任最少 (34.6% 香港政府,18.8%中央政府)。最年輕的

(15 至 19 歲) 最多比例信任香港政府 (48.2%),30 至 39 歲的年齡組

別最多人信任中央政府 (36.1%)。

3.6 到內地升學或就業

受訪者對回內地升學或就業持正面態度,約 40% 接受自己到國內升

學,約 50% 則接受到國內就業,而不同年齡組別之間的差異不大。

雖然年青人在意識及身份方面抗拒建立中國連繫,但關乎個人前途及

發展時,卻非一面抗拒與國內接觸。

3.7 年青人主觀評價發展機會

關於個人在香港得到的發展機會,約 50%受訪者認為機會一般,大

約 30%則認為很少機會甚至完全沒有。比較三個年齡組別,20 至 29

歲的人最不樂觀。

另一方面,近 40%的受訪者認為未來發展機會與現在比較是相近,

14.1%認為會轉好,46.9% 則認為未來發展會比現時更差。20 至 29

歲的受訪者最為悲觀,超過一半 (51.2%) 認為未來會比現時差。

第三,關於個人在香港得到的發展機會,感到滿意 (24.3%) 與不滿

(23.5%)的比例相近。其中最年青的一群(15 至 19 歲)的滿意比例

S-18

(19.2%) 最低,最年長(30-39 歲)的最高 (29.9%)。

3.8 對「佔領中環」及「民間全民投票」的態度

較年輕的兩個年齡組(15 至 19 及 20 至 29 歲)都分別有超過一半人

支持「佔領中環」爭取以他們心中理想的制度於 2017 年普選行政長

官。最年長的一群(30 至 39 歲)則對是否支持「佔領中環」不相上

下,46.7%支持、46.4%不支持。

關於 2017 年以公民提名候選人方式普選行政長官,較年輕的兩個年

齡組都分別有超過 80%受訪者支持,較年長的一組則有 70%。本調

查大部份時間進行期間,有關「民間全民投票」普通行政長官方案還

未開始,受訪者當中只有約三份一人會參加「民間全民投票」。

3.9 香港政府與公民社會的衝突

近年環境保育及土地開發問題屢屢成為政府與民間團體衝突的源頭。

就此類議題,最年長的一群受訪者最支持政府,有 19.5%認同政府立

場,較年輕的兩個年齡組認同政府的分別少於 10%。

各個政黨或政治組織之中,最多受訪者支持的是民主黨 (6.1%),學

民思潮在泛民主派當中最少人支持,但卻最受 15 至 19 歲的受訪者支

持。最年長的一個年齡組最多人(10.5%)支持建制派政黨或組識,

而較年輕的兩個年齡組分別不足 5%支持建制派。

受訪者普遍不滿香港自 1997 年回歸以來的民主發展步伐,超過一半

S-19

人認為民主步伐太慢。不同年齡組別之間有點差異,最少人認為太慢

是 15 至 19 歲組別,但仍有 46.4%;20 至 29 歲則有最多人認為太慢

(62.6%)。

3.10 維護香港高度自治

約 90% 受訪者認同當中港利益在香港出現矛盾時,應該以香港利益

優先。,此外,為體驗香港高度自治,約 80% 分別認同香港政府有權

審批內地來港單程證,及限制內地自由行旅客來港數目。

4. 與青年人異議態度相關的各項因素

4.1 異議者的對社會議題的態度

以 9 項社會議題來量度青年人對整體社會狀況的不滿及異議程度。9

項議題歸納為以下 4 個範疇:

4.1.1 「佔領中環」及「民間全民投票」

(1) 支持以「佔領中環」方式來爭取理想普選行政長官模式:

較年輕的兩個年齡組 (15 至 19 及 20 至 29 歲) 分別有超過

一半人支持;

(2) 同意公民提名方式普選 2017 年行政長官:

不同年齡組別都有大多數人支持:

(3) 參加 2014 年 6 月 22 日「民間全民投票」;

S-20

每個年齡組都有大約三份一合資格投票者,即年滿十八歲或

以上將會投票。

4.1.2 香港政府與公民社會的衝突

(4) 香港政府與民間保育團體就土地開發的衝突;

最年長的一群支持政府立場的比最高(19.5%)

,較年青的兩

個年齡組分別只有不足 10%支持。

4.1.3 政治認同

(5) 支持泛民主派:

最多受訪者支持的是民主黨 (6.1%),學民思潮在泛民主派

當中最少人支持,但卻最受 15 至 19 歲的受訪者支持。最年

長的一個年齡組最多人(10.5%)支持建制派政黨或組識,

而較年輕的兩個年齡組分別不足 5%支持建制派;

(6) 不滿意自 1997 年回歸以來的民主發展步伐:

超過一半人認為民主步伐太慢。不同年齡組別之間有點差異,

最少人認為太慢是 15 至 19 歲組別,但仍有 46.4%;20 至

29 歲則有最多人認為太慢 (62.6%)。

4.1.4 維護香港高度自治

(7) 當中港利益在香港出現矛盾時,以香港利益優先:

約 90% 受訪者認同;

(8) 香港政府有權審批內地來港單程證¡:

約 80% 受訪者認同;

(9) 限制內地自由行旅客來港數目:

約 80% 受訪者認同。

S-21

4.2 累積異議指標

累積異議指標是由上述 9 項議題所表達的異議次數總和,代表累積程

度有多少,數值是 0 至 9 分,分數愈高,異議程度愈高。9 項議題之

中,除了有關公民提名普選 2017 年行政長官一項,其餘 8 項都是 20

至 29 歲年齡組別最高異議程度。

受訪者得 0 分是十分罕見,即是或多或少總有一點異議。大部份受訪

者(67.2%)累積異議指標是介乎 1 至 6 分,可算是低至中度異議者。

大約 32% 是強烈異議者,得分介乎 7 至 9 分。

比較之下,30 至 39 歲是最少異議,平均指標分數是 5 分,亦僅見有

大約 3% 沒有任何異議情緒。

最年青的一群異議程度與最年長的一群幾乎相同,平均分是 5.1,但

當中沒有人是全無異議。20 至 29 歲的異議程度最高,平均分是 5.8,

只有個別 (0.6%) 是全無異議。

整體來說,異議程度愈高者的人口特徵是:男性、在香港出生、具專

上教育程度及家庭收入比較好。具海外居住或求學經驗則對異議程度

沒有影響。大部份人口特徵的異議程度差距其實少 1 分,只有專上教

育程度與初中或以下程度者的差距大約達到 1 分。由此可見,青年人

的不同人口特徵沒有導致異議程度大異。

S-22

4.3 強烈異議者的人口特徵

強烈異議者的比例是顯著的 31.6%,累積異議指標分數是 7 至 9 分,

他們的特徵是甚麼呢?

這批強烈異議者,不論年齡組別,其人口特徵都相近:具專上教育程

度(68.1%)、在香港出生 (82.6%)、並非最草根一層(家庭月入中位數

是$30,000-49,999)

、只有少數人具備海外生活經驗 (11.7%)。

4.4 與異議態度相關的其他因素

三項有關個人發展機會的評價都與異議態度呈相反關係,即是異議程

度愈高,就認為自己發展機會愈少,這些關聯力度不強,但統計學上

還是顯著。換句話說,異議情緒其實不是由於自覺發展機會不好而展

現。調查結果不能證實部份輿論對年青人的普遍印象,就是認為年青

人由於缺乏向上流動機會而對社會產生並累積不滿。

此外,對生活滿意或感覺開心,與異議情緒的關聯程度非常弱小,雖

然統計學上是顯著的。受訪者對生活感到不滿或不開心,其異議情緒

都不會高於感到滿意或開心的人。對自己身體健康狀況的評價與異議

情緒無關。因此,個人對生活的面感覺,不會增強異議態度。

S-23

4.5 政治信任、身份認同與異議態度

不同程度的異議態度於政治信任方面分歧很大。2014 年不信任香港

政府的人,其累積異議指標高於信任香港政府者 2 分(總分 9 分)

。

相近的差異亦見於信任與不信任中央政府的兩群受訪者之中。此外,

信任中央政府的人,累積異議指標最低,比較信任香港政府的人更

低。

4.6 物質主義、後物質主義與異議態度

價值觀對政治最向的影響是顯著的。自上世紀七十年代起,國外學界

便開始對文化價值觀的轉變進行連串研究,檢視由「物質主義」轉為

「後物質主義」的趨勢,如何影響到對社會、政治、經濟狀況的評價。

上世紀九十年代有研究報告指出香港的主流價值觀仍然是物質主義,

但是後物質主義價值開始浮現。

2014 年的調查結果發現,香港青年人口是物質主義與非物質主義並

重。觀察兩類主義的個別項目評分,最高評分一項是關於物質主義的

維持治安,次高評分是後物質主義的保障言論自由。其餘項目評分高

低皆由物質主義與非物質主義輪流排序。由此可見,青年人口的態度

取向並非二分及互相排斥,而是要視乎具體社會及政治狀況而表現那

一方面的傾向。

後物質主義對異議態度有顯著影響。2014 的受訪者,保守派的與異

議者,後物質主義的傾向有別,後物質主義傾向愈強,對社會政治議

S-24

題批判得愈激烈。

4.7 預測異議態度

以上分析發現不同因素都與受訪者的「累積異議指標」高低有關,為

找出當中最具影響力的因素,需要進行多變項迴歸分析,包括:人口

特徵、後物質主義價值觀、身份認同及對政府的信任。

多變項迴歸分析結果顯示,後物質主義傾向的影響是最強烈。人口特

徵的影響在統計學上是不存在。因此,一般印象是愈年青的異議程度

愈高,其實沒有證據支持。人口特徵不能解釋異議程度高低,價值觀

取向才是關鍵。

5. 總結

2014 年的調查於 5 月 14 日至 6 月 24 日進行,即是調查期間是社會

處於一個相對正常的狀態。所謂正常,就是指社會的政治氣氛是我們

常見及生活在其中的狀態。在此期間收集的意見,就是未經刻意動員

面對不尋常政治衝突的局面。因此,調查結果就不是反映極端對立以

至社會撕裂的狀況。以學術研究來說,在正常社會狀態下進行調查,

其實更具學術價值,因為要進行長期追蹤調查,正常的社會狀態是最

常見及持久,最能反映受訪者長期對社會及政治議題的評價。

S-25

I. Background of the Study

This project is a follow-up to a 2010 research commissioned by the

Central Policy Unit.

The idea is to gauge to what extent social and

political attitudes of young people in Hong Kong have changed over the

past several years and the reasons why. We have witnessed an apparent

escalation of social and political participation outside of institutionalized

channels over the past years.

This project should help us ascertain

whether the perception of rising youth activism and dissent towards

public authority is true among the youth population as a whole or a

"localized" phenomenon within small pockets of young people.

It

should also allow us to test a number of prevalent explanations of the rise

in youth activism.

The current project will follow-up on the key findings of the 2010 survey,

focusing on four general questions:

(1) Does the younger generation have unique socio-political orientations

vis-à-vis the older cohort? Are there any distinctive diversity in

values and orientation within this generation?

(2) How does the younger generation perceive their own position and

opportunities in the socio-economic system, and in particular the

chances of improving their social and economic conditions?

(3) More specifically, does the younger generation exhibit a distinctive

kind of post-materialist and "localistic" values?

(4) What are the socio-demographic and biographical factors that could

account for diversities in socio-political orientations among the

1

younger generation?

II. Methodology

This study uses a quantitative approach to gather the required information

on the young population of Hong Kong. The main age cohort under

study includes those born in the years between 1975 and 1999, that is,

those aged 15 to 39 as of the year 2014.

In which the 30-39 cohort are

included as a reference group to compare with the younger population.

A telephone survey was conducted from 14 May to 24 June 2014 by the

Telephone Laboratory of the Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies

at The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

The previous 2010 survey

was also administered by the same Telephone Laboratory.

A total of 2,000 respondents who completed the survey were drawn from

the target population.

The procedures to select this sample followed a

strict probability sampling method and also, as is common practice for

other telephone surveys: only landline household telephone numbers

were generated by computer and then calls were made by interviewers.

If a household contacted had more than one eligible respondent, a

random process was used to select only one respondent from that

household. If the chosen individual was not at home or not free to

answer, follow-up calls were made.

With random selection, we try to

reduce systematic sampling error as much as possible.

The response

rate for the telephone survey was 67.1%, which was calculated from all

telephone calls with known eligible respondent(s) present in the

households.

Telephone numbers without an eligible respondent (i.e. no

household member aged between 15 and 39) were not included in

2

calculating the response rate.

A major limitation of telephone surveys, however, is the shorter attention

span of respondents.

As a result, the number of questions we could

include in our survey was much fewer than the number that could be used

in a typical face-to-face survey.

According to the experience of the

Telephone Laboratory, the maximum number of questions that should be

asked on the telephone is 40 since respondents are likely to hang up once

this threshold is reached so that the interview would be incomplete.

The

questions we asked in the study cover basic demographics, social values,

political orientations, affiliation and participations, acquisition of political

information, life satisfaction, personal development, and postmaterialist

values orientation.

Although we wanted to ask many questions, we had

to limit ourselves to relatively few for each aspect of youth attitudes.

The final version of the questionnaire is found in Appendix 1.

Statistical findings from the survey are reported in the rest of this chapter.

The choice of telephone over household survey is due to balance of time,

cost and sample size.

Conducting household survey has already become

much less efficient than 10 years before, mainly due to tightened security

measures among private housing.

The difficulty to get into dwelling

adds disproportionally higher fieldwork cost.

And because our target

respondents are a subgroup of the general population in terms of age,

successful contact rate should be lower than all adult population, hence

further adding cost and time.

To efficiently survey 2000 respondents of

age between 15 to 39, telephone survey has the advantage of timely

completion of data collection, and therefore reasonable fieldwork cost.

3

III. Telephone Survey on Social Attitudes of the Youth Population in

Hong Kong: May to June 2014

3.1 Demographic Characteristics

Of the total of 2,000 respondents who completed the survey, 1,076

(53.8%) are female and 924 (46.2%) male.

By generational distribution,

362 (18.1%) are aged 15-17, 276 (13.8%) aged 18-19 (in combination,

638 or 31.9% aged 15-19), 780 (39.0%) aged 20-29, and 582 (29.1%)

aged 30-39.

By educational attainment, 7.7% are junior secondary or

below, 39.0% senior secondary, and 53.3% tertiary education or above.

A majority of the respondents (77.1%) were born in Hong Kong.

Of

those not born in Hong Kong, 8.3% have lived here less than 7 years,

40.4% between 7 and 15 years, and the remaining 51.3% 15 years or

more.

Only 12.2% of respondents have experience of living, education,

or working overseas.

The median household monthly income category

is $30,000-$49,999. Classified by economic activity status, 47.0% are

economically active, 42.8% students, and 10.1% economically inactive.

Table 3.1 presents the basic demographic characteristics for the sample as

a whole.

4

Table 3.1 Demographic Characteristics

Female

Male

53.8%

46.2%

Education

Junior secondary or below

Senior secondary

Tertiary education or above

7.7%

39.0%

53.3%

Born in Hong Kong

Not born in Hong Kong

77.1%

22.9%

Lived in HK < 7 years

Lived in HK 7-15 years

Lived in HK 15 years or more

8.3%

40.4%

51.3%

Overseas living experience

No overseas experience

12.2%

87.8%

Median monthly household

income group

$30,000 49,999

Economic Activity Status

Economically active

Students

Economically inactive

47.1%

42.8%

10.1%

3.2 Civic Engagement and Political Information Seeking

Anti-establishment sentiment is reflected in actions of our respondents.

Table 3.2 indicates that half of respondents (50.2%) have not joined any

demonstration or rally since 1997, and a mere 3.2% report having joined

frequently. A visible group of youth population (46.6%) has experience

in civic actions either occasionally or frequently.

5

Table 3.2 How often participating in Demonstrations or Rallies since 1997?

(自 1997 年回歸以來,你有冇參加過示威集會、遊行呢?)

All

%

Never

Seldom

Occasionally

Frequently

Don't know

Total

(N)

p < 0.001

50.2

23.7

22.9

3.2

0.1

100.1

(2000)

Table 3.3 shows that a substantial majority of respondents (88.8%) are

aware of demonstrations or rallies to be organized.

Table 3.3 Awareness of Demonstrations or Rallies to be Organized

(無論以往你有冇參加過示威集會遊行,你事前有冇留意有關消息呢?)

All

%

Aware

Unaware

Total

(N)

88.8

11.2

100.0

(1999)

How do respondents learn about the holding of demonstrations and rallies?

As shown in Table 3.4, the Internet (74.3%) outplays conventional mass

media to become the major channel to receive information on civic

actions to be organized.

TV comes not close enough (60.2%) and

printed newspapers are farther apart (48.3%).

6

Different forms of online

communication are further examined in Table 3.5.

Social network

media and online new media ("new" as opposed to "old" conventional

mass media) are usual electronic communication channels to obtain

necessary information. It is not surprised but more importantly the data

here confirm the anecdotal observations.

Table 3.4 Channels for Learning About Demonstrations or Rallies to be Organized

(multiple responses allowed)

(你主要係靠乜嘢方法得知示威集會遊行嘅消息呢?可選多項)

All

%

Internet (computer, mobile phone,

tablet)

TV

Printed newspapers

Informed verbally by others

Radio

Banners or handbills

School / Teachers

On street propaganda by political

parties

Magazines

Others

Don't know / forget

(N)

74.3

60.2

48.3

25.6

1.0

0.5

0.5

0.1

0.1

0.1

0.1

(1776)

7

Table 3.5 How Users of Electronic Communications Learn about Demonstration or

Rallies to be Organized (multiple responses allowed)

(你主要係靠以下邊個途徑知道示威集會遊行嘅消息呢?可選多項) [只問有用電

腦/手機/平板上網的受訪者]

All

%

Facebook posts / private messages

Facebook Page

Online new media

Instant messaging

Blogs

Mobile phone SMS

Email

Online forum

Others

Don't know / forget

(N)

54.7

51.5

43.7

24.0

8.8

7.8

5.6

2.3

2.9

2.0

(1319)

3.3 Voting Behaviour in the Legislative Council in 2012

About 32% of respondents were not aged 18 or above in 2012, and

therefore not eligible voters then.

As self-reported by the respondents,

1,046 were eligible voters in 2012 Legislative Council Election. Table

3.6 reports that 74.1% voted in 2012, and the figure is much higher than

the official turnout rate of 53.1%.

8

Table 3.6 Voted in LegCo Election in 2012? (Eligible voters only)

All

%

Voted

Not voted

74.9

25.1

Total

(N)

100.0

(1046)

A majority of respondents reported voting for candidates from the

Pan-democrats camp as shown in Table 3.7.

And about 26% of them

did not remember to whom they cast their vote.

Table 3.7 Which Political Camp They Cast Their Vote for in the LegCo Election in

2012 (only those having voted)

All

%

Pan-democrats

(泛民主派)

55.8

Pro-establishment

(建制派)

11.3

Independent /

Neutral (獨立 / 中

間 / 無黨派)

Empty vote

Forgot

Total

(N)

5.8

0.6

26.5

100.0

(724)

3.4 Life Satisfaction

The present survey has assessed satisfaction of respondents with selected

social conditions. Respondents were asked to evaluate three social

conditions relevant to this study, plus the usual overall measures of

9

quality of life.

Satisfaction was measured using a 5-point rating scale: 1

is very dissatisfied, 3 the mid-point, and 5 very satisfied.

Tables 3.8-3.10 show respondents' satisfaction with three social

conditions: political development, environmental conservation, and

economic development.

The results show that the majority of all age

groups have indicated dissatisfaction with two conditions: political

development and environmental conservation. And the economical

development is rated average by half of respondents in all age groups.

The differences among age groups are statistically significant in three

issues, but the trends are the same among age groups.

The differences

are in terms of magnitude only.

Table 3.8 Satisfaction with Political development in HK

Age

15-19

%

20-29

%

30-39

%

52.3

36.7

11.0

69.4

25.6

4.9

58.8

30.3

10.9

60.9

30.6

8.6

Total

100.0

100.0

(N)

(637)

(772)

p < 0.001; 5-point scale, 1=very dissatisfied, 5=very satisfied

100.0

(571)

100.1

(1980)

All

%

Very dissatisfied / dissatisfied

Average

Very satisfied / satisfied

All

%

Table 3.9 Satisfaction with Environmental conservation in HK

Age

15-19

%

20-29

%

30-39

%

54.2

30.2

15.6

59.7

28.4

11.9

47.5

32.3

20.2

54.4

30.1

15.5

Total

100.0

100.0

(N)

(635)

(775)

p < 0.001; 5-point scale, 1=very dissatisfied, 5=very satisfied

100.0

(575)

100.0

(1985)

Very dissatisfied / dissatisfied

Average

Very satisfied / satisfied

10

Table 3.10 Satisfaction with Economic development in HK

Age

Very dissatisfied / dissatisfied

Average

Very satisfied / satisfied

Total

(N)

p < 0.001

15-19

%

20-29

%

30-39

%

All

%

12.1

55.3

32.7

100.0

(637)

26.3

54.7

19.0

100.0

(777)

31.2

45.9

22.9

100.0

(577)

23.2

52.3

24.5

100.0

(1991)

5-point scale, 1=very dissatisfied, 5=very satisfied

Table 3.11 reports findings with respect to assessment of overall quality

of life, measured using the same 5-point scale as described above.

The

mean scores for the overall sample reflect the respondents' generally

positive evaluation towards personal conditions.

The 15-19 age group

is relatively more satisfied with overall life than the other two cohorts.

The differences among cohorts are statistically significant, but the

magnitude is not large.

All respondents are on average slightly satisfied

with their personal life.

Table 3.11 Overall Life Satisfaction

Age

Overall life satisfaction

(N)

p < 0.001

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

3.45

(638)

3.26

(778)

3.28

(580)

3.33

(1996)

Mean scores on 5-point scale:

1=very dissatisfied, 5=very satisfied => higher score, more satisfied

11

3.5 Identity and Political Trust

Respondents indicate they are relatively dissatisfied with broad social

conditions.

Then, would this in turn weaken their choice among

national and Hong Kong identity, and their political trust in the HKSAR

government and Central government?

Table 3.12 shows that an

overwhelming majority of the two younger cohorts (15-19, and 20-29)

identify themselves as Hong Kongers, both over 80%, in contrast to 10%

being Chinese.

The older 30-39 cohort has about 63% of Hong Kong

identification, and about 21% being Chinese.

Comparatively speaking, more respondents have trust in the Hong Kong

SAR Government (42.6%) than in the Central Government (25.2%).

The middle cohort (20-29) has the least trust in both governments (34.6%

Hong Kong, 18.8% Central).

The youngest (15-19) has the most trust in

Hong Kong government (48.2%), and the oldest (30-39) the most trust in

Central government (36.1%).

12

Table 3.12 Identity and Political Trust

Age

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

10.5

10.3

20.6

13.4

9.4

9.0

16.6

11.3

80.1

80.7

62.7

75.3

100.0

100.0

100.0

100.0

(638)

(768)

(577)

(1983)

Trust / Trust strongly

48.2

34.6

47.4

42.6

Do not trust / Do not trust

51.8

65.4

52.6

57.4

(A) Identity

(認為自己是香港人多些,還是中國人多些)

Chinese

Both or both not

Hong Kong

Total

(N)

(B) Trust in HK SAR Government

strongly

Total

100.0

(N)

(616)

(748)

(547)

(1911)

Trust / Trust strongly

23.6

18.8

36.1

25.2

Do not trust / Do not trust

76.4

81.2

63.9

74.8

Total

100.0

100.0

100.0

100.0

(N)

(625)

(739)

100.0

100.0

100.0

(C) Trust in Central Government

strongly

(537)

(1901)

p < 0.001

3.6 Attitudes Towards Education and Employment in the Mainland

Although respondents do not exhibit high level of national identity or

trust the Central Government, they generally welcome opportunities to

study or work in the Mainland.

Table 3.13 shows that more than 40% of

13

respondents find it acceptable to pursue further study in the Mainland.

The percentage is similar across cohorts.

Table 3.14 shows slightly

more positive evaluation towards working in the Mainland.

About 50%

of respondents would be willing to work in the Mainland, and the

percentage is about the same across cohorts.

To summarize, our

respondents are rejecting Chinese identity only at an ideological level.

When it comes to personal life and development, however, the youth

population finds it acceptable to have connections with the Mainland, e.g.

through further studies and employment opportunities.

Table 3.13 Attitudes towards Pursuing Further Studies in the Mainland

Age

Accept / Strongly accept

Reject / Strongly reject

Indifferent

Total

(N)

p > 0.05

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

44.7

53.5

1.9

43.2

53.0

3.9

46.9

47.1

6.0

44.8

51.4

3.9

100.1

(638)

100.1

(780)

100.0

(582)

100.1

(2000)

Table 3.14 Attitudes towards Taking Up Employment in the Mainland

Age

Accept / Strongly accept

Reject / Strongly reject

Indifferent

Total

(N)

p > 0.05

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

51.0

46.0

3.1

51.4

43.9

4.8

51.4

44.2

4.5

51.3

44.6

4.2

100.1

(638)

100.1

(780)

100.1

(582)

100.1

(2000)

14

3.7 To What Extent Youth Perceive Opportunities

Table 3.15 shows the response to the question about the perception of

opportunities available to their same age cohort for personal development.

About 50% of all respondents perceive moderate amount of opportunities

available.

Slightly more than 30% perceive limited or no opportunity

available for their personal development.

Comparatively speaking,

respondents of aged 20-29 are the least positive to the opportunities

available to them.

Table 3.15 Perception of Opportunities Available to Same Age Cohort for Personal

Development in Hong Kong

(你認為同你年齡相近嘅香港人,喺香港各方面發展嘅機會多唔多呢?)

Age

None / Limited

Moderate

Many

Total

(N)

p < 0.05

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

31.2

55.3

13.5

34.3

50.9

14.8

26.5

53.3

20.2

31.1

53.0

16.0

100.0

(637)

100.0

(776)

100.0

(574)

100.0

(1987)

A second question asked respondents about their perception of

opportunities for personal development in future. As shown in Table

3.16, nearly 40% of respondents expect their future would be the same as

now.

With respect to cohort differences, the youngest are the least

pessimistic about their future than others, 14.1% expecting a better

tomorrow, or 46.9% worse than now.

The middle cohort (aged 20-29) is

the least positive, with half of them (51.2%) expecting a worse tomorrow.

15

Table 3.16 Comparing with the present, will opportunities for personal development

in Hong Kong become better or worse in future?

(你認為同你年齡相近嘅香港人,

未來喺香港各方面發展嘅機會,同依家相比,係會好啲、差唔多,定係差啲?)

Age

Worse than now

About the same

Better than now

Total

(N)

p < 0.05

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

46.9

39.0

14.1

51.2

38.9

9.9

49.9

41.0

9.1

49.4

39.5

11.0

100.0

(638)

100.0

(771)

100.0

(559)

100.0

(1968)

A third question asked respondents how satisfied they are with

opportunities for their own development in Hong Kong.

assessment is shown in Table 3.17.

Their overall

Nearly a quarter of all respondents

are dissatisfied with the opportunities available for their own

development in Hong Kong. Satisfied respondents (24.3%) are about

the same as those dissatisfied (23.5%).

Comparatively speaking, the

youngest (aged 15-19) is the least satisfied generation (19.2%), and the

oldest (30-39) the most satisfied (29.9%).

16

Table 3.17 Generally speaking, are you satisfied with the opportunities for your own

development in Hong Kong?

(整體嚟講,你滿唔滿自己喺香港所得到嘅發展機會呢?)

Age

Dissatisfied / Very dissatisfied

Average

Satisfied / Very satisfied

Total

(N)

p < 0.001

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

25.5

55.2

19.2

24.6

51.0

24.3

19.7

50.4

29.9

23.5

52.2

24.3

100.0

(634)

100.0

(778)

100.0

(579)

100.0

(1991)

3.8 Attitudes Towards "Occupy Central" and Civil Referendum

Tables 3.18 to 3.20 reveal the attitudes of youth towards two

controversial issues in Hong Kong recently: the "Occupy Central"

movement and the Civil Referendum organized by the "Occupy Central"

to vote for a proposal to the 2017 Chief Executive nomination.

were 3 proposals and an option of "Abstention".

There

The common element

in the three proposals is popular nomination. It is this common element

that has provoked strong reaction from the establishment.

The younger two cohorts (aged 15-19 and 20-29) have more than half

supporting the "Occupy Central" movement to fight for their ideal form

of universal suffrage in 2017 Chief Executive Election.

The oldest

cohort (30-39) is ambivalent with favourable (46.7%) and unfavourable

(46.4%) responses about the same.

The popular nomination receives

overwhelming support from all age cohorts. The younger two cohorts

have 80% or more, and the oldest about 70% endorsement of popular

nomination.

At most time of the survey period, the Civil Referendum

17

had not yet taken place.

Respondents, however, were not very

enthusiastic to vote in the Civil Referendum.

Only one-third in each

cohort would cast a vote.

Table 3.18 Support "Occupy Central" for Genuine Universal Suffrage in 2017 Chief

Executive Election

(支持佔領中環爭取落實真正普選特首方案嗎?)

Age

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

42.6

34.4

46.4

40.5

53.6

59.7

46.7

53.9

3.8

5.9

6.9

5.5

Total

100.0

100.0

100.0

99.9

(N)

(638)

(776)

(580)

(1994)

Don't support / Strongly don't

support

(唔支持 / 非常唔支持)

Support / Strongly support

(支持 / 非常支持)

Don't know

(唔知道/好難講)

p < 0.001

18

Table 3.19 Popular Nomination of Chief Executive Candidates in 2017 is Indispensable

(認同公民提名是普選行政長官方案中必不可少嗎?)

Age

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

13.1

16.1

24.7

17.6

85.0

80.0

69.4

78.5

2.0

3.9

6.0

3.9

Total

100.1

100.0

100.1

100.0

(N)

(637)

(777)

(580)

(1994)

Disagree / Strongly disagree

(唔認同 / 非常唔認同)

Agree / Strongly agree

(認同 / 非常認同)

Don't know

(唔知道/好難講)

p < 0.001

Table 3.20 Would Vote in "6.22 Civil Referendum" Organized by "Occupy Central" in

June 2014? (For Age 18 or Above )

(佔領中環運動於 6 月 20 日起舉行民間全民投票,請問你會唔會參加呢?只限

18 歲或以上)

Age

18-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

Would not vote (唔會投票)

29.3

24.4

38.5

30.2

Not yet decided (未決定)

37.7

35.8

27.8

33.3

Would vote (會投票)

32.6

38.8

33.0

35.7

0.4

1.0

0.7

0.8

Total

100.0

100.0

100.1

100.0

(N)

(276)

(780)

(576)

(1632)

Don't know

(唔知道/好難講)

p < 0.001

19

3.9 Conflicts between the Government and Civil Society

The conflicts between the administration and civil groups on

environmental conservation and land development are commonly seen.

Table 3.21 reveals that the government has not received support from our

respondents.

The most supportive to the government is from the oldest

cohort with 19.5%.

The younger two cohorts have less than 10%.

Table 3.21 Conflicts between Government and Civil Groups over Land Development

Issues (政府與民間團體就土地開發問題有過多次爭論及衝突,你認同

政府定係民間團體嘅立場呢?)

Age

Support Government more

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

9.2

8.7

19.5

12.0

50.2

46.5

45.0

47.3

39.0

42.6

32.4

38.5

0.5

0.6

1.0

0.7

1.1

1.5

2.1

1.6

100.0

100.1

(582)

(2000)

(完全/大部分認同政府)

Half-half

(政府同民間團體一半一半)

Support Concern Groups more

(完全/大部分認同民間團體)

Support neither

(兩面都唔認同)

Don't know

(唔知道/冇意見)

Total

100.0

(N)

(638)

99.9

(780)

p < 0.001

Table 3.22 reflects the political identification of the youth.

20

For

responses of named parties, the Democratic Party is the most identified

with (6.1%).

Although Scholarism has the lowest percentage to be

named among the pan-democratic camp, it is the third most popular in

the 15-19 cohort. For the pro-establishment camp, the most supportive

is the 30-39 cohort with 10.5%, while less than 5% from the two younger

cohorts.

Table 3.22 Political Party Most Supported (最支持香港邊個政黨或政團呢?)

Age

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

8.0

5.5

4.9

6.1

6.4

5.7

3.7

5.4

Civic Party (公民黨)

3.3

6.8

5.7

5.4

League of Social Democrats

2.5

5.7

3.0

3.9

4.1

1.2

0.5

1.9

4.9

7.4

7.3

6.6

4.2

4.6

10.5

6.2

66.6

63.2

64.5

64.6

Total

100.0

100.1

100.1

100.1

(N)

(638)

(768)

Democratic Party

(民主黨)

People Power

(人民力量)

(社民連)

Scholarism

(學民思潮)

Pan-democrats

(其他民主派/泛民主派)

Pro-establishment

(建制派)

Independent / Neutral

(獨立 / 中間 / 無黨派)

(574)

(1980)

p < 0.001

It is not unexpected that, as shown in Table 3.23, the youth population is

21

not satisfied with the democratic progress in Hong Kong since 1997.

More than half find the progress too slow. Interestingly, the youngest is

the least (still 46.4%) feeling too slow the democratic progress, and the

aged 20-29 the most (62.6%).

Table 3.23 Democratic Progress since 1997

(自 1997 年回歸以來,你覺得香港民主發展步伐方面係太快、太慢,定係適中呢?)

Age

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

5.6

4.5

6.2

5.4

About right (適中)

46.2

31.3

35.9

37.4

Too slow (太慢)

46.4

62.6

51.9

54.3

1.7

1.7

6.0

3.0

Total

99.9

100.1

100.0

100.1

(N)

(638)

(780)

Too fast (太快)

Don't know

(唔知道/好難講)

(582)

(2000)

p < 0.001

3.10 Defending for Autonomous Hong Kong Administration

One of the most heated controversies in Hong Kong in recent years is

defending for the autonomy in the administration of Hong Kong.

The

voice is even louder when conflict between China and Hong Kong is

involved.

Tables 3.24 to 3.26 illustrate the relevant issues. Across all

cohorts, near 90% of respondents insist that the interests of Hong Kong

must prevail whenever conflicts between Hong Kong and China occur in

Hong Kong.

About 80% of respondents in each cohort are in favour of

autonomous administration of Hong Kong, as reflected by the approval

22

of One-way Permit Scheme and imposing quota for Individual Visit

Scheme for the Mainland residents.

Table 3.24 Hong Kong Interests Prevail when Conflict between China and Hong Kong

(中港利益矛盾在香港發生時,香港人權利優先)

Age

Disagree / Strongly disagree

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

12.2

6.4

12.4

10.0

86.2

91.8

84.7

88.0

1.6

1.8

2.9

2.1

100.0

100.0

100.0

100.1

(唔認同 / 非常唔認同)

Agree / Strongly agree

(認同 / 非常認同)

Don't know

(唔知道/好難講)

Total

(N)

(638)

p < 0.001

23

(780)

(582)

(2000)

Table 3.25 One-way Permit Scheme for Mainland Residents to Hong Kong Approved

by Hong Kong Government

(香港政府取回內地來港單程證審批權)

Age

Disagree / Strongly disagree

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

25.2

12.1

16.8

17.7

71.2

84.1

76.5

77.8

3.6

3.8

6.7

4.6

100.0

100.0

100.0

100.1

(唔認同 / 非常唔認同)

Agree / Strongly agree

(認同 / 非常認同)

Don't know

(唔知道/好難講)

Total

(N)

(638)

(780)

(582)

(2000)

p < 0.001

Table 3.26 Quota for Individual Visit Scheme for Mainland Residents must be Limited

(限制內地自由行旅客來港數目)

Age

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

14.7

13.2

19.4

15.5

84.3

85.0

78.2

82.8

0.9

1.8

2.4

1.7

Total

99.9

100.0

100.0

100.1

(N)

(638)

(779)

Disagree / Strongly disagree

(唔認同 / 非常唔認同)

Agree / Strongly agree

(認同 / 非常認同)

Don't know

(唔知道/好難講)

p < 0.001

24

(582)

(1999)

IV. Correlates of Dissent Youth in Hong Kong

4.1 Social Attitudes of Dissent

One of the research objectives of the present study is to examine the

perceptions and attitudes of socially discontented youth.

We have

measured the extent of their discontent by 9 social attitudes reflected in

their responses to the following questions grouped in 4 areas.

Detailed

statistics are reported in previous tables, and brief results are recapped as

follows:

4.1.1 Attitudes Towards "Occupy Central" and Civil Referendum

(1) whether or not they support Occupy Central for genuine

universal suffrage (Table 3.18);

(2) whether or not agree Popular Nomination for Chief Executive

election in 2017 (Table 3.19);

(3) whether or not would vote in 22 June 2014 civil referendum

(Table 3.20);

In this area, the younger two cohorts (aged 15-19 and 20-29) have more

than half supporting the "Occupy Central" movement to fight for their

ideal form of universal suffrage in 2017 Chief Executive Election.

The

popular nomination receives overwhelming support from all age cohorts.

At most time of the survey period, the Civil Referendum had not yet

taken place.

Eligible respondents (i.e. age 18 or above), however, were

not very enthusiastic to vote in the Civil Referendum.

Only one-third in

each cohort would cast a vote.

4.1.2 Conflicts between the Government and Civil Society

25

(4) which side they support in various incidents of conflicts between

the HKSAR Government and concern groups on land

development issues (Table 3.21);

On land development issues, the government has not received support

from our respondents.

The most supportive to the government is from

the oldest cohort with 19.5%.

The younger two cohorts have less than

10%.

4.1.3 Political identification

(5) which political party in Hong Kong they most support (Table

3.22);

(6) their evaluation of democratic progress in Hong Kong since

1997 (Table 3.23);

The Democratic Party is the most identified with (6.1%). Scholarism

has the lowest percentage to be named among the pan-democratic camp,

however, it is the third most popular in the 15-19 cohort.

For the

pro-establishment camp, the most supportive is the 30-39 cohort with

10.5%, while less than 5% from the two younger cohorts.

It is not unexpected that the youth population is not satisfied with the

democratic progress in Hong Kong since 1997.

More than half find the

progress too slow.

4.1.4 Defending for Autonomous Hong Kong Administration

(7) whether or not agree Hong Kong interests take priority when

China & Hong Kong in conflict (Table 3.24);

(8) whether or not Hong Kong SAR Government must have

26

approval right of One-way Permit (Table 3.25); and

(9) whether or not agree Hong Kong to restrict visitors via

Individual Visit Scheme (Table 3.26).

Across all cohorts, near 90% of respondents insist that the interests of

Hong Kong must prevail whenever conflicts between Hong Kong and

China occur in Hong Kong.

About 80% of respondents in each cohort

are in favour of autonomous administration of Hong Kong, as reflected

by the approval of One-way Permit Scheme and imposing quota for

Individual Visit Scheme for the Mainland residents.

4.2 Aggregate Measure of Dissenting Attitudes

The above 9 social attitudes of dissent and political affiliation indicate

how much discontent the youth population has towards the socio-political

environment. To further analyze their "aggregate" level of dissent and

identify the most discontented group, we have created an aggregate

measure by counting how many of the following positions the

respondents have expressed:

(a) supporting Occupy Central for genuine universal suffrage;

(b) supporting Popular Nomination for Chief Executive election in 2017;

(c) would vote in 22 June 2014 civil referendum (for age 18 or above);

(d) supporting environmental concern groups on land development

issues;

(e) having a democratic affiliation;

(f) finding democratic progress too slow since 1997;

(g) Hong Kong interests taking priority when China & Hong Kong in

conflict;

(h) Hong Kong SAR Government gaining approval right of One-way

27

Permit;

(i) restricting visitors to Hong Kong via Individual Visit Scheme.

Table 4.1 summaries the proportion of respondents showing dissenting

attitudes towards the 9 social issues.

Attention is drawn on the middle

age cohort. Except the popular nomination for Chief Executive election

in 2017, the respondents in the 20 to 29 age cohort are the most

dissenting comparing to other two cohorts.

The measure of "aggregate dissent" has a range of values from 0 to 9, 1

point given to each of the 9 issues as shown in Table 4.1.

the score, the more discontented a respondent is.

28

The higher

Table 4.1 Percentage of Respondents with Dissenting Attitudes: A Summary

Age

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

%

%

%

%

53.6

59.7

46.7

54.0

84.9

80.1

69.3

78.5

32.6

38.8

32.7

35.6

39.0

42.6

32.5

38.5

(5) Democratic camp affiliation

29.2

32.3

25.1

29.2

(6) Democratic progress too slow

46.4

62.6

51.9

54.3

86.2

91.8

84.7

87.9

71.2

84.1

76.5

77.8

84.3

85.0

78.2

82.8

(1) Support Occupy Central for

genuine universal suffrage

(2) Support popular nomination for

Chief Executive election in 2017

(3) Would vote in 22 June 2014

civil referendum (for age 18 or

above)

(4) Support environmental concern

groups on land development issues

since 1997

(7) Hong Kong interests taking

priority when China & Hong Kong

in conflict

(8) Hong Kong SAR Government

has approval right of One-way

Permit

(9) Demand restricting visitors to

Hong Kong via Individual Visit

Scheme

Table 4.2 Aggregate Dissent Score & Dissent Intensity

29

15-19

20-29

30-39

All

"Baseline"

Aggregate Dissent

% of

Score 0-9

respondents

%

%

%

(Dissent Intensity

0.0-1.0)

0 (0.0)

0.0

0.6

3.1

1.2

1 (0.1)

2.0

1.4

4.8

2.6

2 (0.2)

5.2

4.4

9.1

6.0

Little or

3 (0.3)

10.7

9.1

13.2

10.8

moderate

4 (0.4)

20.8

14.7

14.3

16.6

dissent

5 (0.6)

21.3

14.1

14.6

16.6

6 (0.7)

18.2

15.3

10.3

14.8

Strong

7 (0.8)

12.2

15.4

11.0

13.1

dissent

8 (0.9)

6.3

15.5

11.2

11.3

3.3

100.0

9.5

100.1

8.4

100.0

7.2

100.0

(78.2)

(59.0)

(77.5)

(67.2)

(21.8)

(40.4)

(19.4)

(31.6)

Mean (out of 9) ***

5.1

5.8

5.0

5.3

S.D.

1.8

2.1

2.4

2.1

No dissent

9 (1.0)

Total

(Score 1-6 subtotal)

(Score 7-9 subtotal)

*** p < 0.001

As shown in Table 4.2, respondents showing nothing dissent (i.e., score 0)

are rarely found, 67.2% of all respondents are a little or moderately

dissenting (with scores from 1 to 6).

Alternatively speaking, a major

majority of them possess little or moderate level of dissent intensity (0.0

being no dissent, 1.0 full dissent).

About 31.6% of respondents are

reported to be holding strong dissenting attitudes (scores 7 to 9, dissent

intensity 0.8 to 1.0). Regarding generational differences, the "baseline"

30-39 cohort is relatively the least discontented, with the lowest mean

score of dissent 5.0; about 3% of them do not show any discontent (with

30

zero dissent score.)

The youngest generation (age 15-19) is as much (or

as less) discontented as the oldest, with mean score of dissent 5.1.

However, no one in the youngest generation reports zero score.

The

middle generation (20-29) has the highest dissent score of 5.8.

But

interestingly, a tiny proportion (0.6%) of the middle generation reports

zero dissent.

On the other hand, the 20-29 cohort has the largest proportion to show

strong dissent.

About 40% of them possess dissent score from 7 to 9, or

dissent intensity 0.8 to 1.0.

The youngest and the oldest cohort have

more or less the same proportion of strong dissent, with 21.8% and

19.4% respectively.

Apart from generation differences in the mean score of aggregate dissent,

there are also some statistically significant differences in dissent scores

by demographic characteristics as summarized in Table 4.3. In general,

the more dissenting respondents are male, born in Hong Kong, tertiary

educated, and in more economically well-off household.

Overseas

living experience has no statistically association with the aggregate

dissent measure.

For those statistically significant differences, the

magnitude is mostly less than 1 (i.e., 1 social issue among 9 under

survey). This narrow difference (less than 1 social issue) has already

been found among generations (Table 4.2).

The most divided

demographic subgroups are those tertiary educated against those junior

secondary or below, and the difference is said to be as "large" as 1 social

issue apart.

Demographically speaking, the overall youth population is

not hugely divided.

31

Table 4.3 Demographic Characteristics and Dissenting Attitudes

Dissent Score

Sex ***

Female

Male

5.1

5.5

Born in Hong Kong ***

Not born in Hong Kong

5.5

4.8

Education ***

Junior secondary or below

Senior secondary

Tertiary education or above