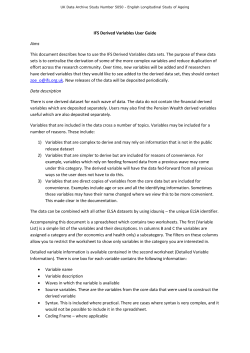

Knowing Left from Right