In Defence of Ancient Bloodletting

SA

28 Julie 1979

MEDIE

I::

TYD

KRIF

149

Histol'Y 01 Medicine

In Defence of Ancient Bloodletting

P. BRAIN

SUMMARY

The ancients used bloodletting extensively in infectious

and other diseases. When recent work on iron and bacterial

infection is taken into account, it is possible to argue

that bloodletting, which reduced plasma iron and transferrin saturation, might have been of value in increasing

resistance to infection by bacteria or plasmodia. Galen's

bloodletting methods are summarized, and their probable

effect on plasma iron is considered. The ancient physicians, who had no specific remedies for infection whatsoever, may well have been justified in making responsible use of bloodletting, both for the treatment and for

the prophylax:s of infectious disease.

S. Afr. med. J., 56. 149 (1979).

The ancients used bloodletting extensively as a general

therapeutic measure. a practice that began before Hippocrates and became extinct, except for a few special indications, within living memory. Until a few years ago it

would probably have been impossible to put forward a

rational justification of the ancient practice in the light of

modern pathology. I believe, however. that when recent

work on iron and bacterial infection is taken into account

it is possible to argue that the general use of venesection

in infectious disease, which prevailed in antiquity. may have

been justified in the circumstances then obtaining. I attempt such an argument in this article.

By far the most extensive account of bloodletting in

antiquity is that of Galen. In addition to numerous references in other books, he has left 3 extensive works on venesection,' the first dating from his arrival in Rome for the

first time in AD 162. when he was in his early thirties. and

the third from the closing years of his life, some 30

years later. Since no English translations of any of them

have ever been published. it is not surprising that they are

little known today. They offer, however, much interesting

information on Galen's personality and on medical practice

in Rome in his time, in addition to his views on venesection.

Galen used venesection both as an evacuant and as a

revulsive or derivative remedy, but only its use as an

evacuant is relevant to the present argument. The writers

of the Hippocratic corpus in the 5th and 4th centuries

BC, although Galen would like to think otherwise.

generally used venesection only occasionally and in moderation; Galen, on the other hand, employed it in all the

acute infectious diseases and in others. too. as long as the

Natal Blood Transfusion Service, Durban

P. BRAIN. :\1.A .. :\1.0 .. Medical Director

D.lle received:

I

March 1979.

patient's strength permitted and certain other conditions

prevailed. He did not originate this practice. Celsus say

that in his own time, the beginning of the Christian era.

it was a new doctrine that venesection should be used in

almost all diseases,' and this idea does not appear anywhere in the Hippocratic corpus except once in the

Appendix to the work Regimen in Acute Diseases. This

appendix is a lengthy collection of disjointed notes,

generally regarded as spurious (if, indeed, anything in

the Corpus can be regarded as genuine); hence part of

it may well be late. The relevant pas age reads: 'In the

acute diseases you will phlebotomise if the disease appears

severe, and the patients are in the prime of life and in

possession of strength',' and Galen remarks that it i worthy

of Hippocrates and that he should have included it in the

Aphorisms! He is less complimentary about other parts

of the same Appendix,' which makes it clear that he does

not attribute the whole of it to the father of medicine.

Galen employed venesection in the acute diseases both

when the disease was already severe and when it was expected to be so. 'The magnitude of the disease, therefore,

together with the strength of the powers, are the chief

indications for phlebotomy: the first a showing what one

must do, the second as not forbidding it by what ome of

the younger physicians call a contra-indication. For sometimes the patient's condition demands phlebotomy, while

the weakness of the powers forbid it. When both of these

indications require it, it is clearly catled for.'"

This does not apply only when disease is already present.

but also when it is incipient:

'For not only when severe disease is already pre ent is

it the time for phlebotomy, but also whenever it is likely

to occur. The doctrine that Hippocrates enunciated ha

anticipated us by teaching that however much we may

rightly do once diseases are already pre ent, it is nevertheless better for us to forestall them by acting at their beginnings or when they are about to begin. Thu it i possible to carry over the said indication to people in

health. For you will phlebotomise these too when there

is a likelihood that they will be eized with a evere

disease. taking into consideration their age and their

trength. For if someone is apt to fall into a severe di ea e,

even if no sign exists anywhere in the body. we think it

proper to perform phlebotomy. It is enough to con ider

the patient's age. with his strength, 0 that the three thing

comprising the decision are the magnitude of the disease.

whether present or expected; the tage of life in the prime.

and the strength of the power .'7

Prophylactic venesection of the kind mentioned above

should take place at the beginning of spring;" we are told

ature of Man that blood inin the Hippocratic work

crea e in pring. Patient who had u tained injurie

150

SA

MEDICAL

thought likely to be followed by inflammation were al 0

venesected prophylactically. Even the empiricist physicians,

ay Galen, who based their treatment on experience alone,

used it in this way when some part of the body had been

brui ed.9 Galen believed that in u ing venesection he was

imitating nature. Even irrational brutes, he says, evacuate

themselve by provoking vomiting and giving themselve

enemas, as the ibis doe :'.

'Does nature not evacuate all women every month,' he

a k , 'pouring forth the uperfluity of the blood? . . . Jf

you could learn what great benefit the female sex enjoys

from this evacuation, 1 don't know how you could delay

further and not hasten by every mean to evacuate superfluous blood . . . A woman who is well cleansed is not

eized with gouty or arthritic or pleuritic or peripneumonic

diseases, and neither epilepsy nor apoplexy nor dyspnoea

nor loss of speech ever come on at any time if she is well

cleansed. Was a woman ever seized with phrenitis or lethargy or spasms or tremors or tetany while her periods were

coming? or did you ever know a woman to suffer

from melancholy or madness or haemoptysis or haematemesis, or headache, or suffocation from synanche, or from

any of the major and severe diseases, if her menstrual

secretions were well established? If they are suppressed

again, she is certain to fall into every sort of evil, and when

the evacuations return. they are healing remedies. But

leave the women now and come to the men, and learn

how a many as habitually evacuate the excess by means

of a haemorrhoid, all pass their lives unaffected by

diseases; while those in whom evacuations have been restrained have fallen into the gravest illnesses. Will you not

evacuate even these of blood, not even if they should fall

into a synanche, or into peripneumonia, but through refu ing to retract your erroneous opinions allow so many to

perish? You, perhaps, will do this; 1, on the other hand.

have often cured not only these diseases, but also spasm

and dropsy, by evacuation of blood.'"

Galen regarded a moderate evacuation as 3 cotyles (about

800 ml) of blood." He did not venesect children under

the age of 14 years; in older children, I cotyle might be

removed, followed by a further half cotyle later, if necessary." Even thin people, he said, could have too much

blood; this was what was wrong with an anorexic girl

who had not menstruated for 8 months, so he removed

3 Roman pounds (about I I) over 3 days, which cured

her." Copious venesection, up to 6 pounds (2 I) in one operation, was in Galen's opinion a most effective means of

extinguishing the flame of severe fevers; the amount, however, depended on the patient's strength, and some could

not tolerate the removal of more than a pound and a haiL"

During these heroic evacuations, which continued until the

patient lost consciousne s, his trength, as indicated by the

pulse, had to be carefully watched; Galen knew of three

doctor who had killed patients by evacuating them in thi

way." It wa not always necessary to take the full amount

at one operation; sometime, particularly when there was

an accumulation of crude humour, it might be spread

over everal days. Thi was known a epaphairesis (repeated removal).'~

The Hippocratic belief in beneficial evacuations, whether

by the menses, haemorrhoids, or phlebotomy, which Galen

JOUR

AL

28 July 1979

trongly upported, was no doubt current for many centurie thereafter; by 1946, however, most doctors would

certainly have said that, except in a few special conditions,

there wa no advantage in losing blood. In that year, however, Schade and Caroline'" described a plasma protein.

tran ferrin, which has the property of binding iron. The

iron in the plasma (as distinct from that in the haemoglobin) normally exists bound to transferrin rather than free,

since there is more transferrin than is necessary to bind

the amount of iron that enters the plasma. In normal ubject the transferrin is 30 - 40"{, aturated, and at this level

the binding i extremely firm. As the transferrin saturation increases, however, the binding becomes looser, so

that the transferrin is more easily deprived of some of its

iron, for instance by invading bacteria. Bacteria require

iron, and many species cannot grow in normal human

plasma unless iron is added, the reason being that they

cannot detach iron from the transferrin at its normal level

of saturation; if, however, enough iron is added to saturate

it fully, any excess will exist free in the plasma and bacterial growth will be greatly encouraged. Some bacteria

have developed iron-binding compounds of their own (mycobactin in the case of Mycobacterium Illberculosis) which

are efficient enough to compete with transferrin for iron.

The higher the transferrin saturation, the easier it is for

bacteria to grow; it is not surprising, therefore. that a

natural mechanism exist by which, at the onset of bacterial infection, plasma iron, and hence also transferrin

aturation, falls sharply."

A normal adult has about 4 g of iron, of which about

half is in the haemoglobin and the rest in the iron stores.

principally in the liver. (Plasma iron makes up an insignificant proportion of the total.) When the body is depleted of iron by the removal of red cells, iron is mobilized from the stores, and red cell production is not much

affected until these are almost exhausted. Only then does

the haemoglobin fall to abnormally low levels.'" Plasma

iron, similarly, does not fall to unusually low levels,

de pite losses of blood, while any stores remain; never·

theless it and the transferrin saturation are somewhat

lower in people who are losing blood, such as women

during the reproductive period, than in those who

are not. It has recently become possible to estimate the total

iron stores by the simple method of determining the serum

ferritin level; I Jig ferritin per litre is an indication of about

8 mg storage iron, although this may not apply in all ab·

normal conditions. Z1 It is thus possible to determine easily

whether the subject is in iron balance, i.e. whether losses

in the stools, through the skin and by bleeding are being

made up by absorption of iron from food, so that the

tore remain constant. If more is lost than is absorbed.

the subject is in negative balance and stores decline; if

more is absorbed than is lost, the balance is positive and

stores increase, as they do in many Black men in South

Africa because of the large amounts of iron in their

traditional diet.

Since, then, in plasma at least, it is more difficult for

bacteria to grow if iron and transferrin saturation are at

low levels, it might be argued that this would apply to all

the body fluids and, hence, that in conditions where bacterial infections were prevalent, it might be to the subject'

:2

Julic 1979

SA

MEDIE

advantage to be iron-deficient. The beneficial eva uations

of the Hippocratic authors. in fact, might have been beneficial after all. Is there any evidence that this might be so?

It might be thought that the physicians of the 19th

century were still under the influence of the Hippocratic

writers if they believed this. but the testimony of Trousseau, a most acute clinician, is nevertheless of interest.

He wrote: 'When a very young physician, I was called to

see the wife of an architect, suffering from neuralgia, a

pale woman, presenting every appearance of chlorosis; I

prescribed large doses of preparations of iron ... fn less

than a fortnight there was a complete change: the young

woman acquired a ravenous appetite and an unwonted

vivacity; but her gratitude and my delight did not last

long . . . A short cough supervened, and in less than a

month from the commencement of the treatment, there

appeared signs of phthisis which nothing could impede.'

He wrote of another patient, 'a girl of fifteen, who after

a mild attack of dothinenteria fell into a state of anaemia

and prostration, which I considered chlorosis. I administered ferruginous remedies, which rapidly restored her to

florid health; and although there was nothing in the family

history to lead me to fear the coming calamity, she was

simultaneously seized with haemoptysis and menorrhagia,

and died two months afterwards with symptoms of phthisis_

which had advanced with giant strides. I do not blame the

iron for having caused this calamity; but [ do blame myself

for having cured the anaemia, a condition, perhaps, favourable to the maintenance of the tuberculous affection in a

latent state.''''

Trousseau wrote that very few doctors shared his views,

but that his conviction of their truth increased daily. In

fact. von Niemeyer. the eminent] 9th century authority on

tuberculosis, expressed the contrary view. which is the

orthodox one today. to the effect that the better the

nutrition the better the prognosis. There has recently_

however. appeared some evidence that suggests that Trousseau may have been right. When food shelters were provided for starving nomads in the Ogaden desert, bacterial

and plasmodial infections, previously latent, were lighted

up as soon as they were given a good diet." The same

phenomenon had been observed by others in the treatment of kwashiorkor: there was a grave danger of overwhelming bacterial infection when a good diet was given

to these children.'" apparently because the transferrin. in

common with other plasma proteins. is reduced in consequence of malnutrition. and thus a small amount of

iron will aturate it fully and permit free growth of

bacteria. The same phenomenon has been observed in

domestic cattle. which are free from outward signs of

infection while they are short of food, but become clinically

ill when the rains arrive and food becomes plentifuL'" The

authors of the Ogaden studies have suggested, in fact,

that some such mechanism is an ecological necessity, preventing, by an increased resistance to infection, the total

annihilation of the specie in times of famine, and at the

ame time the unbridled increase of numbers in time of

plenty. through an increased susceptibility to infectious

disease."

There i a significant remark in the Hippocratic work

E

TYD

KRIF

151

all/re of Mall, to the effect that in epidemic the body

hould be kept as thin and weak as possible.'" The observation that the state of the highly trained athlete i a

dangerous one also appear more than once in the Corpus.'"

A study specifically implicating iron in the mechanism has

recently been published by the Murrays.'" Somali nomad

who were not malnourished were studied. The diet of

these people i low in iron, and many of them are irondeficient. while otherwise not badly nourished. Of 94

nomads entering the camp, 64 were not iron-deficient according to the criteria adopted,31 and 26 were iron-deficient.

ineteen of the non-deficient subjects, but none of

the deficient ones. howed evidence of infection (malaria

parasites in blood smears. tubercle bacilli in sputum, fever

of unknown origin. pneumonia, hepatiti , eye infection.

brucellosis, etc.). The authors then collected all the available

iron-deficient subjects who showed no evidence of infection, and divided them into 2 groups. The first group of

71 subjects was treated with 900 mg of ferrou sulphate

by mouth daily for 30 days; the control group, numbering

66, received tablets containing no iron. Haemoglobin.

plasma iron. and transferrin saturation increased notably

in the first group. The interesting finding, however, was

that this group had far more epi~odes of infection during

the period of treatment than the group receiving the inactvie tablets. Only ] of the placebo group, compared

with 13 in the group receiving iron, had clinical evidence

of malaria, while malaria parasites appeared in the blood

of 21 of the treated group. but only in that of 2 of the

controls. Tuberculosis was reactivated in 3 of the treated

group_ but in none of the placebo group. In all, there were

46 episodes of clinical infections of various kinds in the

treated group. as against 3 in those receiving the placebo.

The authors suggest that iron deficiency probably play

a part in suppressing certain infections, suggesting that in

Somali nomads it may be part of an ecological corn promi e. Their diet i deficient in iron: 'The iron deficiency.

debilitating in some but rarely fatal. prevent the more

serious consequence of potentially fatal infections with

malaria. tuberculosis. and brucellosis to which the nomad

are constantly exposed . . . It may be unwise to attempt

to correct iron deficiency in the face of quiescent infection. especially in isolated societies where the natural

ecological balance is often a first line of iefence against

severe infections.'

[t is at lea t arguable. therefore. that in certain circumstances iron deficiency might be desirable. TO one would

suggest that it should be encouraged in civilized countrie

today. since we have better method of dealing with infection than the ancients possessed; but the physician of

antiquity was not in this fortunate position. He had no

specific remedie at all. If he could reduce plasma iron

and transferrin saturation by bloodletting. or by omitting

to treat beneficial natural evacuations. he could perhaps

increa e his patients' resistance to infectiou di ease. H. in

Galen's time, the woman who was well cleansed by her

menses was. in fact. somewhat iron-deficient. she might

well have been in the same po ition a the Murray'

Somali nomads: the minor degree of debility from the

anaemia was a small price to pay for very considerable

immunity from the clinical manife tation of infection.

152

SA

MEDICAL

for which, once they had appeared, there wa no specific

treatment whatever. And the problems of ancient medicine were, for practical purposes, all problems of infection. Malaria, remarks Jones," was undoubtedly the greatest medical problem of antiquity; together with bacterial

diseases of the chest it provided the ancient physician

with most of his work. The only question is how rich in

iron the diet in antiquity was, and what the effects of

bleeding, whether natural or therapeutic, were. These

effects will be considered first.

Fortunately, although bleeding as a therapeutic measure has been almost entirely abandoned, there is abundant information available from blood donors. A single

donation of whole blood, say 400 ml, removes about 200

mg of iron in the form of haemoglobin; Galen would

have regarded it as a small evacuation. Many donors, however, give blood repeatedly at intervals which may be as

short as 2 months, and may thus lose more than 2 I of blood

a year. It has been estimated that a daily loss of 6 - 8 ml,

as a result, for example, of bleeding piles or hookworm

infestation, may put a patient into negative iron balance

even on a normal diet, since even with the increased absorption that prevails in iron deficiency, not enough can

be absorbed from the diet to make up for it.'" This

amount is about the same as that given by a donor who

donates once every 2 months. Laurell'" has published some

figures on the effects of giving blood on serum iron and

transferrin saturation. Seventeen donors, most of whom had

given one previous donation several months before, were

tested before and 1 week after donating 400 ml of blo~d.

The mean serum iron was 117 ,,ug/dl, and the mean transferrin saturation 37%, before the donations; a week

later the figures were 79 .,ug/ dl and 23 ob respectively. This

would be a temporary effect, but might none the less be

significant when a patient was bled at the onset of infection,

as was Galen's practice. A group of 17 donors who had

given repeated donations, totalling between 1,5 and 3 I

per donor in the preceding year, had a mean plasma iron

level of 95 ,ug/ dJ, and mean transferrin saturation of 27%.

These studies were conducted in Sweden immediately

after World War n, and suggest that. at least in the dietary

conditions then prevailing, the loss of even 400 ml of blood

had some effect on plasma iron and transferrin saturation.

while the loss of 2 I or thereabouts in the course of 1 year

reduced both these levels considerably. Laure1J'" also stu·

died 11 patients with haematological signs of iron deficiency. as a result of chronic bleeding from the gut or

uterus. The mean haemoglobin level was nearly

g/d\.

JOUR

28 July 1979

AL

the mean plasma iron level was 33 .ug/dl and the mean

transferrin saturation was 8 %. These patients would no

doubt correspond to some of those in antiquity who were

enjoying beneficial evacuations from haemorrhoids or

menorrhagia, which the doctors refrained from treating;

this is clear from two observations of Galen's. He says that

bleeding from haemorrhoids was sometimes so severe as

to kill the patient, or to leave him grossly hydropic or

cachectic;" such haemorrhoids would, of course, be treated.

In the management of patients who had not reached this

stage, however, doctors sometimes planned totally unnecessary treatment in an attempt to satisfy them, while

leaving their evacuations unchecked.'"

Further information can be obtained from a study of

blood donors in South Africa. If Galen's methods were

applied to this modern population, what might their effects

be? His moderate evacuation of 3 cotyles removes about

400 mg of iron as haemoglobin, and a single such evacu·

ation should thus precipitate a subject with a plasma ferritin of less than SO ,ug/I into iron deficiency anaemia. In

Table I the serum ferritin levels for new donors (before

any donations have been given) in Durban are shown. The

population groups differ in dietary habits. The means for

Whites are almost identical with those found in Washington State, USA." In Table I it is made clear that the

majority of the women, and an appreciable proportion of

the men, would be rendered anaemic, or brought to the

verge of anaemia, by just one of Galen's moderate evacuations, and that few (except some of the siderotic Zulu

men) could withstand his more heroic ministrations with

haemoglobin levels intact.

The iron content of ancient diets is crucial to the argument. If the diet of most of Galen's patients contained

the same amount of iron as modern Western diets, his

bloodlettings would have approximately the effects mentioned. If, on the other hand, there was as much iron in it

as there is in the diet of the average middle-aged Black

man, the effects would be far less_ Jacques Andn?' has

published a fully documented study of Roman diet, from

which some indications of iron content can be obtained.

There is nothing to suggest that the staple diet of cereals.

vegetables and oil was particularly rich in iron; this would

have been obtained chiefly from meat and from wine.

There is, again, no evidence that the consumption of

animal flesh exceeded that of today; in the early centuries

the Roman diet was in fact largely vegetarian, although

more meat was eaten later. Unless we can discover some

article of diet which contained large amounts of iron and

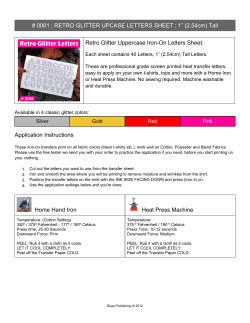

TABLE I. SERUM FERRITIN LEVELS IN DURBAN BLOOD DONORS

Population group

White

Black (Zulu)

Indian

Sex

Male

Female

Male

Female

Male

Number of

subjects with

serum ferritin

level

Number of

donors

examined

Mean serum

ferritin level

(,ug/I)

SD

96

100

99

100

100

93

36

223

32

65

27

275

41

43

64

<SO,ug/1

26

81

17

85

42

2

Julie 1979

SA

EDIE

was taken in very large quantitie

like the traditional

sorghum beer of the modern Black man, who may take

in 150 mg iron a day in beer alone - it is unlikely that

the average patient in Galen's time was in positive iron

balance. Such an article of diet might have existed,

however, in the wine of antiquity. ome red wine today

contain twice a much iron as traditional African beeL"

although they are admittedly usually drunk in smaller

quantities; nevertheless, some French red wine drinker

become siderotic. as do Black. It is possible, therefore,

that the red wines of antiquity contained ubstantial

amounts of iron: on the other hand, they were invariably

drunk diluted with water. There is some evidence that

the wine of poorer quality derived from later pressings

of the grapes might have contained more iron; this is

particularly so of the worst wine. made by macerating

the exhausted skins in water and returning them to the

press. From these the elder Cato prepared 'un horrible

vin d'hiver' for his laves. diluting 260 parts of this

pressing with 1 500 parts of a mixture of fresh and sea

water, vinegar and heated wine. The ration for a slave

engaged in the hardest labour was at most a litre a

day." which, allowing 100 mg iron per litre in the original

pressing. could scarcely, in view of the dilution, have provided more than 10 or 12 mg of iron, most of which in any

case would not be absorbed. Slaves with lighter duties got

only a quarter of this amount.

How much the free man drank depended. of course, on

the price. Under Diocletian, a century after Galen, half a

litre of the best wine sold at the price of a kilogram of

pork, while the same amount of vin ordinaire could be got

for a quarter of that amount. The ratio i almost the same

in South Africa today. Andre's conclusion is that the price

of wine was not excessive at any tage of Roman history,

but on the other hand was never so low that the poor

could use it habitually. Athenaeus, who flourished at about

the time of Galen's death, made the surprising observation

that at that time neither women nor lave in Rome drank

wine, and that the free man began doing so only at the age

of 30." Although women were certainly forbidden wine in

Rome up to 200 BC. Galen mentions it use to bring on

the menses," and we have already seen that the elder Cato

gave wine (if this mixture can be so described) to his laves.

It therefore seems unl ikely that Athenaeus was reporting

correctly the situation in the time of Galen. although it

might well be that most women. through a combination

of tradition and domestic circumstances (fewer parties!)

still drank substantially less wine than men did. thus unwittingly rendering their beneficial evacuation even more

beneficial because of an iron-deficient diet.

It seems likely. therefore, that there was no more iron

in the diet of the average Roman in Galen's time than

there is in ordinary Western diets today, and that many

women, if not men. were therefore in negative iron balance. That this was so in Galen's time. if my thesi is correct. would appear from Galen's observation that women

who had copious menstrual evacuations were protected

from many diseases. as were men who had bleeding

haemorrhoids.

Although there i now ome theoretical ground for believing that iron deficiency might have thi protective effect

E

TVD

153

KRIF

and some evidence that it is 0 in pra tice, it mu t be made

clear that the problem i not imple. Cau ation in medicine

i always complex. the result of many factors which

have different, and ometime oppo ite, effe t . There is

evidence that cell-mediated immunity i defective in iron·

deficient ubjects," uggesting that such ubject might be

more rather than le . u ceptible to viru disease; and

furthermore, there is no doubt that iron deficiency anaemia.

by \ eakening the patient. might decrea e re i tan e to

di ease. Galen was clearly aware of this, since he took into

account the patient'

trength when onsidering veneection, and stopped the evacuation at once if it eemed

to be failing. Hi use of epaphaire i is interesting; by

taking blood in repeated smaller amounts rather than in

one large one he could reduce plasma iron and transferrin

aturation without dangerously diminishing the blood

volume and imperilling life. My the is i that. in the conditions prevailing in Galen's time. the good effect of

moderate iron deficiency. in increasing resistance to certain

infections, outweighed the bad effects of debilitating the

patient. If, by removing blood. the physician of the time

was able to prevent, or to keep latent, infections that, once

established, he was powerle

to cure. he wa right in

using phlebotomy. This wa clearly the experience of most

practitioners, since Galen tells u tliat the empiricist school.

who abjured all theory and based their treatment purely

on experience, all made use of it. Tt wa not. however.

universally practised by competent phy icians: the great

exception was Erasistratus'" That uch a man could acquire

a distinguished reputation without ever employing vene·

section show that its benefits were not so entirely obviou

that no one could ignore them and make a uccess of

practice. Erasistratus. however. like his master Chry ippu .

wa an exception. Almost every other celebrated physician

of antiquity. and for many centuries thereafter. made ome

use of the remedy: is it conceivable that they were all

completely wrong?

REFERENCES

C. G .. ed. (1964): Clalld,i Gale"i Opera Omnia, 20 vol,.

Hildesheim: G. Olms. (Reprint of the 19th century edition.) Abbreviated

to K. The 3 works are in K XI. pp. 147 - 316.

Celsus: De Medici"a, H. 10.. I.

littre, E., ed. (1962): Qellvres completes d'Hippocrate, 10 vol'.

Amsterdam: A. Hakken. (Reprint of the 19th century edition)

Abbreviated to L. The passage is in L 2. 39 .

K XV, 763.

e.g. K XV, 891. 893.

K Xl, 289 - 90.

K XI, 277 - 8.

K XI, 27I.

K X, 27.

K X, 16. The ibis. according to one old auth.,r. . purges itsell

I. Kiihn,

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

9.

10.

at tbe fundament with its crooked beak.'

I I.

12.

13.

14.

IS.

16.

17.

1 .

19.

20.

11.

22.

23.

K Xl, 165 - 6.

K XI. 174.

K XI, 290 - 91.

K XVI lb.

I. As she was of a prominent family. Galen sub·

sequently received many such patients. whom he cured in the ~ame

way. This is perhaps the first account of anorexia nervosa in the

literature. and Galen's cure was presumably psychologica1.

K XI. 294.

K Xl, 2 - 9.

K Xl, 2 6.

Schade, A. L. and Caroline. L. (I 46):

ience, 104. 340.

For reviews of the topic ee Weinbers. E. D. (1974): Science, 184,

952: Kochan. I. (1973): Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol.. 60. I'

Bullen. J. J.• Rogers. H. J. and Grifliths. E. (197 ): Ibid .• 80. I.

Bothwell. T. H. and Finch. C. A. (1962): Iron Metabo/lsm. p. 2 I

London: Churchill Livingstone.

Jacobs. A. (1977): Semin. Haemat.. 14. 89.

Trousseau, A. () 6 - 72): l.eClures 0" Clinical AIel/idOl!. vol

V,

D.

9. London:

ew Sydenham Society.

Von Niemeyer. F. (I 70): Clinical Lec/urn 011 Plllmollary Con·

sumption. London:

lew

ydenham

iety

A

154

MEDICAL

24. t\1urray.

J .. i\1urray. 1\1. B..

1urrJ.Y. A. B. et al. (1976) :

L1.ncet, I. 12 3.

t\.1cFarlane. H .. Reddy. S.. Adcock. K. J. et 0/. (1970) : Brit. med. J ..

4. 26 .

ciety of Medicine (1937) : Proc. roy.

26. Royal

oc. I\led .. 30. 1039

and 1O~9.

27. Murray. M. J. and Murray. A. B. (1977) : Lancet. I. 123.

2 . L 6. 56.

29. e.g. L 9, 110.

30. Murray, M. J .. M Lirray. A. B.. Murray. M. B. et al. (197 ): Bnt.

med. J .. 2, 1113.

31. Haemoglobin less than 11 g/dl. serllnl iron less than 25 !'g/dl.

transferrin saturation less than 15%. with hypochromia and micro·

cYlosis in the meaT.

32. Jones, W. H. S. (trans.) (1923): HipPOCTlllf!..'i. vol. I. pp. Ivi· Ivii.

2-

33.

34.

3 -.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

28 July 1979

JOUR TAL

London and Cambridge. 1ass: Loeu ClaSSiC.l) Libr~r)'.

BOlhwell and Finch. p. 315.

LaureIl, C-B. 09:+7): Acta physiol. sc::md.. 1-1. <;juppl. ~6. S2.

K Xl, 307.

K XI. 170.

Worwood. M. (1977): Semin. Haemat.. 1·1. 21.

Andre, J. (1961): L'A{imemQtioll et la CUOllle f; Rome. Parl~

Klincksieck.

Jacobs. pp. 9 ·9.

Andr';. pp. 164· 5.

Andr';. pp. 170· I.

K XL 205.

Joynson. D. H. M .. Jacobs. A .. Walker. D. M. et al. (1972):

Lancet. 2. 1058.

Galc:l's first work on venesection is a polemic against Ensistralll"_

Curiosa Paediatrica

n

THEODORE lAMES

SUMMARY

A small series of a dermal curiosity occurring in children

is described. It appears not to have been presented

heretofore in medical writings and certainly not in our

South African medical literature. The constancy of its

presentation suggests strongly a genetic localization for

its origin (if not a fanciful one!) and the name foveae

scapularum cutaneae bilaterales congenitae in true dermatological fashion is wholly descriptive, ponderous

though it be for such light 'residua pennarum'!

S. A/,.. med. l., 56. 154 (1979).

During recent years I have collected a small series of

6 children, ranging in age from I to 6 years, with a curious

dermal anomaly. The presenting complaints of the children

were entirely unrelated. One of the 6 children was brought

to me by a colleague to whom I had demonstrated the

feature with its striking constancy. owhere in the nume·

rous departments of our medical literature have I seen

a mention of the curiosity, which deserves recording if

only for its surely genetic origination.

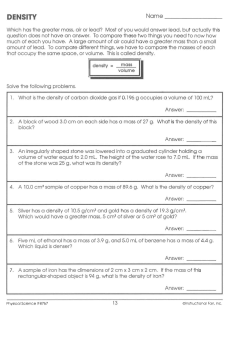

Fig. 1 shows scapular dimples which occur over the

acromions of the spines of the scapulas. In 5 instances

the symmetry and sameness of the dimples were remarkable; in the 6th child the right dimple was less in

Pinelands, CP

TflEODORE J:\\IE·.

Date received:

24 Octoher

~I.Ll.

197

(,I

LB.

Fig. 1. Scapular dimples.

depth than its twin on the left, but distinct, nonetheless.

That the dimples are congenital I have no doubt. although the youngest exhibitor was only a little less than

I year old. The oldest in the series had turned 5 years.

All were Coloured children, and therefore of mixed blood.

but there is no contributory evidence that the anomaly

is necessarily genetically connected with pigmentation of

the skin and no famili()l relationship among the children

could be determined.

I cannot even venture to guess at the dermato-ana·

tomical significance of the genetic nature implicit in its

constancy other than a whimsical 'residua pennarum·.

but a suitable name for it would be foveae scapularum

cutaneae bilaterales congenitae. satisfactory for a dermal

curiosity of unknown origin.

© Copyright 2026