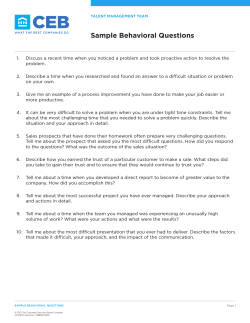

ATTC WHITE PAPER: - ATTC Addiction Technology Transfer Center