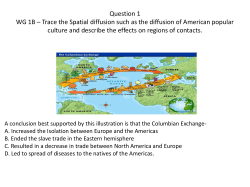

Gender & post-Soviet discourses