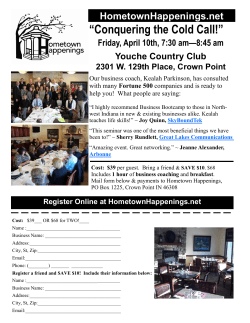

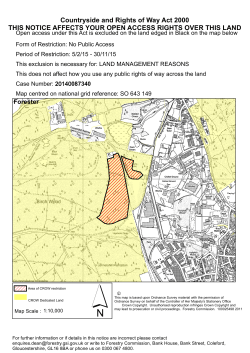

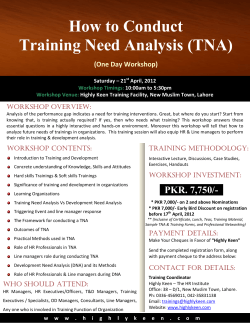

Document