Relationship Dynamics: Understanding Continuous and

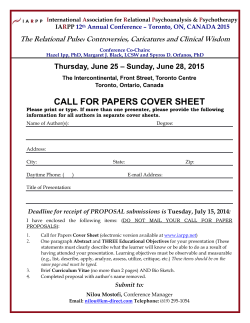

Relationship Dynamics: Understanding Continuous and Discontinuous Relationship Change In Handbook of Research on Distribution Channels, Charles A. Ingene, and Rajiv P. Dant, Editors, Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing (Forthcoming) Colleen Harmeling Post Doctoral Researcher Michael G. Foster School of Business University of Washington 359 MacKenzie Hall, PO 353200 Seattle, WA 98195 Tel: 206-543-4348 Fax: 206-543-7472 [email protected] Robert W. Palmatier Professor of Marketing John C. Narver Endowed Chair in Business Administration University of Washington Michael G. Foster School of Business Box 353200 Seattle, WA 98195 Tel: 206-543-4348 Fax: 206-543-7472 [email protected] 1 Research on relationship marketing and its use in business practice has grown exponentially (Palmatier et al. 2006). Although relationships are critical to both business-to-consumer and business-to-business exchanges, the interdependent nature and essential long-term orientation of channel relationships make managing these exchange relationships especially critical. Strong relationships with business partners enhance channel performance by improving new product launches, insulating channel systems from competitive actions, and promoting investments that accelerate sales growth. Understanding how to develop long-term, profitable exchange relationships thus is essential to improving performance. Relationships evolve over time, through encounters between exchange partners. Lifecycle theories of relationship development that dominate marketing literature describe this evolution as a continuous process, in which repeated interactions and strategic efforts build incrementally on a stable history between the exchange partners (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh 1987; Heide 1994; Ring and Van de Ven 1994). Such research primarily has focused on identifying key relational constructs, describing relationship stages, investigating key moderators, and determining the antecedents and outcomes of exchange relationships. It perpetuates the assumption that all relationships follow a common trajectory of incremental movement through a “fairly rigid sequence of … stages” (Jap and Anderson 2007, p. 260), Consequently, little research investigates discontinuous relationship development. Recent empirical studies of the dynamic aspects of relationship development, such as movement across stages, patterns of change, and relationship velocity, offer some evidence of the existence and importance of dramatic relationship changes. For example, in an empirical test of lifecycle models of relationship development, Jap and Anderson (2007) provide initial support for rapid changes in exchange relationships: Nearly one-quarter of the relationships they studied did not follow a traditional lifecycle trajectory. By using a hidden Markov model to examine transitions 2 between relationship stages, Netzer, Lattin, and Srinivasan (2008) determine that a single event can increase the likelihood of relationship transformation by 58%. In their study of relationship velocity, Palmatier et al. (2013) find that both the rate and the trajectory of change in a relationship significantly influence overall performance. These combined results thus imply that exchange relationships can undergo dramatic shifts in trajectory that are important to performance; a single exchange encounter also can have critical effects on the transformation process. If this is the case, it becomes critical not only to identify patterns of relationship change but also to investigate how individual exchange encounters affect relationship development and what determines their relative effects (incremental vs. dramatic). Extant lifecycle theories suggest that exchange encounters build on one another, to create an accumulated impression of the relationship (Ring and Van de Ven 1994). Yet relationship research outside of marketing suggests that single encounters can spark “turning points” that mark dramatic transformations in the underlying relationship (Baxter and Bullis 1986; Bolton 1961; Graham 1997). This chapter explores both continuous and discontinuous relationship development. We start by identifying three underlying dynamic relationship constructs—trust, commitment, and exchange partner identification—and their importance in relational exchanges. We then review research on continuous (i.e., lifecycle theories) and discontinuous (i.e., turning point theories) relationship changes, thereby specifying their unique drivers, underlying mechanisms, and impact on key relationship constructs. Finally, we discuss strategies for building and recovering relationships, based on both lifecycle and turning point theories. Dynamic Relationship Constructs Relationship marketing research cites several constructs that guide relational processes, though trust and commitment consistently emerge as essential to successful relationships (Morgan and Hunt 1994; Narayandas and Rangan 2004). In addition, exchange partner identification or self3 definition in the relationship affects each partner’s role in the exchange, as well as interpretations of any actions taken in the relationship (Lewicki, Tomlinson, and Gillespie 2006; Ring and Van de Ven 1994). Thus, exchange partner identification is elementary to relationship success, and nurturing its development, along with trust and commitment, is critical for the development of successful long-term relationships. Figure 1 depicts a model of the relationship development process, revealing how exchange encounters can facilitate continuous or discontinuous relationship change through relationship-building or relationship-transforming mechanisms that affect trust, commitment, and exchange partner identification. -Insert Figure 1 about here Developing Trust Developing, managing, and repairing trust in exchange relationships may be the single most critical aspect of relational exchanges (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). Trust is “confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity” (Morgan and Hunt 1994) and “an expression of confidence between the parties in an exchange … that they will not be harmed or put at risk by actions of the other party” (Jones and George 1998, p. 531). High levels of trust allow exchange partners to focus on the long-term benefits of the relationship, reduce transaction costs, increase competitiveness, and ultimately enhance performance (Doney and Cannon 1997; Williamson 1975). In exchange relationships in which interdependence creates vulnerability, trust operates as a governance mechanism that reduces opportunism (Dwyer et al. 1987). Trust also reduces conflict and increases satisfaction in the relationship (Anderson and Narus 1990). Finally, trust signals an exchange partner’s intention to remain in the relationship over time and provides a foundation for commitment (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Developing Commitment 4 Commitment refers to exchange partners’ beliefs that “an ongoing relationship with another is so important as to warrant maximum efforts at maintaining it” (Morgan and Hunt 1994, p. 23). Commitment increases cooperation, financial performance, and market penetration (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Moreover, it signals the importance of the relationship to the partners and reflects their assumption that this relationship will provide future value for them (Wilson 1995). Recent research suggests that the dynamic content of a relationship—specifically, its “commitment velocity or the rate and direction of change in commitment” (Palmatier et al. 2013, p. 13)—constitutes important information that contributes to relationship performance. Developing Exchange Partner Identification Trust and commitment have been the focus of research for more than two decades, but research into relationship developments also suggests that exchange partners’ perception of self affects their behaviors within the exchange and overall relationship performance (Koza and Lewin 1998; Ring and Van de Ven 1994). In exchange relationships, exchange partner identification captures the degree to which exchange partners “perceive themselves and the focal organization as sharing the same defining attributes” (Ahearne, Bhattacharya, and Gruen 2005, p. 574). High levels of identification are associated with customer advocacy, extra role behaviors, greater efficiency, and extreme loyalty (Pratt 2000; Ahearne, Bhattacharya, and Guen 2005). Marketing researchers recognize “identification as the primary psychological substrate for the kind of deep, committed, and meaningful relationships that marketers are increasingly seeking to build with their customers” (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003, p. 76). Thus, exchange partner identification is a critical often overlooked construct that is important to relationship development. Identification is a reflection of the exchange partners’ definitions of themselves in the relationship, which serves as a filter for organizing “self-relevant actions and experiences … and has motivational consequences, providing the incentives, standards, plans, rules, and scripts for 5 behavior” (Markus and Wurf 1987, p. 299). Identification affects every aspect of an exchange, through language, behaviors, and interpretations of information about the relationship (Van Maanen and Schein 1979). As identity becomes increasingly integrated across exchange partners, beliefs about the other become more self-referential or -defining (Pratt 2000), such as when the language used to refer to the other party changes from “them” to “us,” signaling an affective and psychological shift in how the exchange partner regards him- or herself in the relationship (Albert and Whetten 1985). Identification allows the exchange partner to “‘think like’ the other, ‘feel like’ the other, and ‘respond like’ the other,” increase decision-making efficiency, and help see the world from the partner’s perspective (Lewicki and Bunker 1996, p. 123). Because people invest resources in protecting and bolstering their self-concept, strong identification provides a unique motive to support and defend the relationship against threats, as a means to protect the sense of self (Tajfel and Turner 1985). Ultimately, strong identification with the exchange partner promotes helping behaviors in the relationship that are relatively enduring because, once altered, identity is very difficult to change (Markus and Wurf 1987). Table 1 provides a summary of these dynamic relationship constructs. Trust, commitment, and exchange partner identification constitute three dynamic elements of exchange relationships. Through encounters between exchange partners, the meaning, importance, and configuration of these underlying relationship constructs fundamentally shift (Anderson 1995). Both lifecycle and turning point theories provide insight into the role of exchange encounters for motivating and facilitating relationship change, the mechanisms that underlie the change, and the influence of such changes on the key relationship constructs. -Insert Table 1 here Continuous Relationship Change: Lifecycle Perspective 6 Trust, commitment, and exchange partner identification do not come naturally but instead must be cultivated carefully and developed through interactions between exchange partners. Lifecycle theories, which build on interpersonal relationship research, often use a marriage metaphor, in which the relationship grows, matures, and declines, to describe the process of relational change. Exchange Encounters and Continuous Relationship Change Lifecycle theories suggest that exchange relationships develop through a “sequence of events and interactions among organizational parties that unfold to shape and modify an [exchange relationship] over time” (Ring and Van de Ven 1994, pp. 90-91). Each encounter contributes to the overall accumulation of events that incrementally build on past events. Because they are relatively non-distinct (Jap and Anderson 2007), encounters can be understood using existing relational norms, such that they get assimilated or accommodated with incremental adjustments that build on the relationship’s history (Sherif and Hovland 1961). Thus, lifecycle theories describe relationship development as path dependent, such that exchange partners construct an overall impression of the relationship through their accumulation of prior encounters. Developmental Mechanisms of Continuous Relationship Change In lifecycle theories, exchange relationships provide both the content and the platform for three developmental mechanisms that promote incremental relationship change: demonstration, negotiation, and learning. Demonstration is a process of providing proof or evidence of the existence or truth of something. Exchange encounters are concrete demonstrations of the exchange partners’ intentions, capabilities, values, expertise, and needs (Bitner 1995). With accumulated, consistent demonstrations of their abilities and trustworthiness, exchange partners begin to envision a future in which the relationship is more stable and mutually beneficial, strengthening their commitment (Dwyer et al. 1987; Ring and Van de Ven 1994). Thus, demonstrations allow each 7 party to discover similarities and differences in their values, goals, and capabilities, and adjust their relationship accordingly. Exchange encounters also provide a platform for negotiation, the active process of establishing and attempting to influence the joint expectations, nature, and processes that guide an exchange (Ganesan 1993; Ring and Van de Ven 1994). It takes place when exchange partners present, persuade, and debate the terms and processes for their relationship (Ring and Van de Ven 1994). This push-and-pull form of bargaining between parties gradually transforms the relationship until it meets each partner’s needs. Resource investments, which reinforce and signal commitment to the relationship, are negotiated in an attempt to maintain balance between the exchange partners (Jap and Ganesan 2000). Finally, the lifecycle perspective suggests that exchange encounters affect development by facilitating learning, which is critical to successful relationships (Arino and De La Torre 1998; Eisenhardt and Martin 2000). Learning involves “continual processes of organizational adaptation and strategic alignment” through knowledge transfer, knowledge sharing, and knowledge generation (Lukas, Hult, and Ferrell 1996, p. 239). Critical to this process is the development of relational capabilities, “a firm’s learned ways of behaving in its [exchange relationship], including procedures and policies in [exchange relationship] management” (Johnson, Sohi, and Grewal 2004). Although some learning occurs overtly, through deliberate education and training, much of the knowledge exchanged in relationships is tacit, not easily imitated or transferred (Teece 2007). Learning thus occurs through experience, observation, replication, and trial-and-error processes, while exchange partners interact with each other (Arino and De La Torre 1998). That is, knowledge is transferred through repeated exchange encounters that build on and are influenced by the relationship’s history. Thus, from a lifecycle perspective, exchange encounter incrementally change relationships over time through demonstration, negotiation, and learning, which affects how 8 exchange partners interpret information, and improves performance. Incremental Changes in Relationship Constructs According to lifecycle theories, exchange encounters build on the relationship history suggesting that each encounter is easily understood using existing relational expectations. Relational expectations refer to perceived mutual obligations that characterize an exchange relationship, including perceptions of appropriate behavior, roles, and investments in the relationship (Robinson, Kraatz, and Rousseau 1994). When events confirm relational expectations, lifecycle theories suggest they incrementally move the relationship through a series of predetermined stages through demonstration, negotiation, and learning. In early, exploratory stages, trust is based on some estimate of the degree of difference between each party’s core values and morals. Assuming too much trust at the onset of a relationship increases the risk of exploitation. Thus, early in the relationship when, knowledge of exchange partner is limited, the uncertainty associated with estimating their moral character creates a significant degree of doubt about exchange partners’ trustworthiness (Jones and George 1998). However, through repeated encounters, Jones and George (1998) suggest that trust changes in breadth from a conditional, “in which both parties are willing to transact with each other, as long as they behave appropriately,” to unconditional trust, such that “each party’s trustworthiness is now assured… [and] backed up by empirical evidence derived from repeated behavioral interactions.” Conditional trust facilitates cooperative behavior to the extent that each party maintains its good standing to the other within the confines of similar transactions. Unconditional trust implies cooperative behavior that entails some degree of personal cost and self-sacrifice, largely reliant on an assurance of shared values (Jones and George 1998). This description is similar to another description of the evolution of trust, in which it changes in form, from calculative to relational, as relationships develop (Lewicki et al. 2006). Calculative trust reflects a cost–benefit analysis of the economic exchange, which depends 9 on credible information about the intentions and competence of the other party (e.g., reputation, certifications) (Rousseau et al. 1998). Thus, at early stages, deterrence elements of trust—supported by laws and social sanctions—dominate over the benefit-seeking elements (Lewicki and Bunker 1996) and trust is limited to specific exchanges. As the relationship develops, calculative trust evolves into relational trust, which is based on information provided by the focal relationship and supported by emotional connections and attachment between the two parties (Lewicki et al. 2006; Rousseau et al. 1998). It applies to a broader variety of interactions, rather than simple replications of previous interactions. Wilson (1995) suggests that in early stages, trust gets actively negotiated between the two parties; in later stages, it becomes more latent or “settled to the manager’s satisfaction,” such that it no longer receives managerial time or attention. Lifecycle theories outline the processes that incrementally change the level of involvement and form of trust as relationships evolve. Repeated demonstrations of acceptable behavior form the basic foundation for trust by serving as empirical evidence to support predictions of future behavior and generating expectations about actions within the relationship (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). In addition, because trust is informed by feelings, satisfying encounters “cement the experience of trust” by evoking positive moods and providing evidence of equity and efficiency (Jones and George 1998, p. 534). Negotiation allows exchange partners to evaluate each other’s trustworthiness, assess the investments and risks associated with the exchange, and construct appropriate roles (Ring and Van de Ven 1994). Furthermore, negotiation influences trust, because exchange partners observe each other’s responses to different social encounters and thereby infer information about their value systems (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). Finally, exchange partners learn to trust each other by gathering data about their wants, preferences, and approaches to problem solving; observing the partner in different contexts; and experiencing the partner in different emotional states (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). 10 According to lifecycle theories commitment evolves through different predetermined stages as well. Early in the relationship, each party assumes very little risk and initiates small, “trial” deals that enable them to exit the relationship easily if needed (Ring and Van de Ven 1994). As transactions repeat and meet basic expectations of performance and equity, exchange partners increasingly feel reassured and increase their investments in the relationship. Exchange partners demonstrate their commitment to the relationship through idiosyncratic investments, assets that are “customized to their relationship and difficult to redeploy without significant loss of productive value” (Jap and Anderson 2007, p. 263). Investments of this nature serve as credible commitments and reassurances of each party’s efforts to maintain the relationship (Jap and Anderson 2007, p. 263). Idiosyncratic investments also increase interdependence between exchange partners, because each partner’s offering grows increasingly specialized and therefore more difficult to source elsewhere; at the same time, investments used to create this specialized offering become more difficult to redeploy elsewhere (Anderson and Narus 1990). Consequently, negotiation is used to establish balance between the partners. In addition, learning facilitates the development of greater technical skills and interests, which increases commitment to the relationship (Sheldon 1971). Lifecycle theories identify predetermined stages of exchange partner identification (Koza and Lewin 1998; Ring and Van de Ven 1994) such that an exchange partner’s identity shifts from an outsider, or a view of self as completely autonomous, to an insider, or a view of self that is defined in part by the incorporation of the exchange partner’s identity (Pratt 2000). Johnson et al. (2004) describe this shift in four steps, from stranger to acquaintance to friend to partner. Lewicki and Bunker (1996) suggest that identification is the highest form of trust, at which point the exchange partner acts on the other’s behalf, with no loss of quality or satisfaction in the relationship. Demonstrations, negotiation, and learning facilitate incremental movement through these stages of exchange partner identification. Demonstrations promote the discovery of similarities and 11 overlaps in identity between exchange partners, which should facilitate identification. Identity negotiations arise from an internal need for a sense of self in relation to others and a desire for order in social relationships (Ring and Van de Ven 1994). When exchange partners negotiate each other’s roles, exchange partner identity evolves to accommodate these new, negotiated positions. Learning also is a key aspect of socialization, by which exchange partners adopt a common language, shared values, and understanding (Van Maanen and Schein 1979). Ultimately, this shared learning leads to the creation of shared “mental models,” which refer to “generalizations and hypotheses on how to understand the environment and how to take actions accordingly” and represent an essential aspect of exchange partner identification (Lukas et al. 1996, p. 235). Even further, identification signals “second order” learning, because exchange partners understand what really matters to each other (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). From a lifecycle perspective, exchange encounters thus contribute to overall relationship development by facilitating demonstration, negotiation, and learning that incrementally move the relationship toward a predetermined, more relational state of exchange. Relationship development is cumulative, continuously and incrementally building on a stable relationship history (Ring and Van de Ven 1994). Table 2 summarizes the underlying mechanisms of incremental relationship change. - Insert Table 2 about here Discontinuous Relationship Change: Turning Point Perspective Logic suggests that exchange encounters are not homogeneous in their impacts on relationships (Bitner 1995). Empirical research also shows that a single positive encounter can move a relationship to a different “conceptual plane of loyalty” (Netzer et al. 2008, p. 186). Conversely, a single negative encounter, such as disintermediation (i.e., selling directly to a customer and circumventing the distributor), discontinuing product lines, opportunism, policy changes or new enforcement, and employee turnover, can undermine an exchange relationship, with 12 potentially devastating effects on its persistence (Antia and Frazier 2001; Hibbard, Kumar, and Stern 2001; Seggie, Griffith, and Jap 2013). Although extant marketing research shows that single events can dramatically affect relationship development, the processes underlying discontinuous relationship development have received little research attention. Social psychology research on “turning points” in interpersonal relationships suggests some drivers and underlying processes of event-based discontinuous relationship change (Baxter and Bullis 1986, , p. 469; Graham 1997; McLean and Pratt 2006). A turning point is “an event or incident that has impact and import. Turning points trigger a reinterpretation of what the relationship means to the participants. These new meanings influence the perceived importance of and justification for continued investment in the relationship” (Graham 1997, p. 351). Because relationship change takes a dramatically different form, the role of events and the mechanisms of change vary between lifecycle and turning point perspectives. Exchange Encounters and Discontinuous Relationship Change Whereas lifecycle theories stress continuous movement through predetermined stages of relationship development, turning points mark relationship change that “is not simply an addition or an unfolding of an existing theme, but a reformulation” (Bolton 1961, p. 236). Contrary to lifecycle theories, which conceptualize exchange encounters as relatively non-distinct and easily assimilated, a turning point perspective suggests that specific exchange encounters can contrast with and challenge relational expectations, “bringing certain characteristics of the relationship into focus” and prompting rapid transformations (Graham 1997, p. 351). According to turning point theory, exchange encounters not only change the future outlook, but can also alter individual perceptions of past events. For example, upon learning that a supplier has offered deeper discounts to another customer, the focal customer might begin to view previous “favors” from the supplier with 13 suspicion. Turning point theories suggest that exchange encounters thus can challenge relational expectations, prompting dramatic reevaluations and significant redefinitions of a relationship. Transformational Mechanisms of Discontinuous Relationship Change Exchange encounters, from a turning point perspective, contrast with the history of the relationship, rather than building on it (Planalp, Rutherford, and Honeycutt 1988), so the mechanisms underlying relationship change in this context differ from those typically studied using a lifecycle perspective. That is, the mechanisms that underlie incremental change tend to be strategic and deliberate, whereas those that explain dramatic relationship change are instinctual and reactive (Planalp et al. 1988). Encounters that contrast relational expectations are defined by their ambiguity and uncertainty, which heighten the affective, cognitive, and behavioral resources allocated to responding (Sherif and Hovland 1961) and trigger three transformational mechanisms that fuel discontinuous relationship change: social emotions, behavioral reciprocity, and relational sensemaking. Compared with lifecycle theories, turning point theories grant a much more functional role to emotions for motivating relationship change. Although all unexpected encounters heighten the resources allocated to develop responses, encounters that contrast with relational expectations spark social emotions in particular (Nesse 1990). Social emotions establish the psychological system for monitoring and controlling an overall cooperative society and include gratitude and betrayal (Trivers 1971). When an encounter exceeds relational expectations, it is interpreted as a favor or extra effort, beyond the requirements defined by relationship norms, so it prompts feelings of gratitude. Gratitude is emotional appreciation for benefits received, and customer gratitude influences “how people perceive, feel about, and repay benefits gained in the exchange process” (Palmatier et al. 2009, p. 2). Although gratitude facilitates the development of long-term reciprocity norms and promotes the development of trust (Emmons and McCullough 2004), it arises only when 14 actions exceed the requirements defined by the relationship (i.e., extra effort) and are interpreted as benevolent rather than self-interested. Conversely, because relational expectations reflect implicit rules that determine what is equitable or appropriate in the relationship, an event that violates relational expectations prompts negative social emotions, namely, a sense of betrayal due to the failure to uphold basic trust and presumed agreements (Nesse 1990). This “key motivational force … leads customers to restore fairness by all means possible” (Grégoire and Fisher 2008, p. 247). Feelings of betrayal offer diagnostic signals that the relationship is in trouble (Lewicki and Bunker 1996); furthermore, betrayal can shatter the very foundation of trust, motivating a violated partner to signal to the wider network and potential customers that the partner is disreputable (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). Evolutionary psychologists suggest that social emotions such as gratitude and betrayal, constitute a well-developed psychological system for maintaining essential networks of cooperation in society (Trivers 1971). Thus, emotions fuel and guide dramatic relationship transformation. Furthermore, social emotions often drive people to pursue relationship-building or relationship-destroying behaviors. Gratitude creates an “ingrained psychological pressure to reciprocate” that, if not fulfilled, can result in guilt or embarrassment (Palmatier et al. 2009, p. 2). In exchange relationships, gratitude drives reciprocal behaviors, manifested as increased repurchase intentions, share of wallet, sales growth, or helping behaviors (Palmatier et al. 2009). Betrayal instead tends to have a blinding effect and leads to punishing behaviors, even if they harm the violated party too (Grégoire and Fisher 2008). Punishing behaviors seek to harm the violator, counteract its offensive action, and signal to both the violator and others that its behavior was unacceptable (Trivers 1971). In exchange relationships, punishing behaviors include reduced sales, deliberate sabotage, negative word of mouth, and so forth (Grégoire and Fisher 2008). 15 Finally, social emotions also guide cognitive responses by filtering the information that each party recalls, attends to, and interprets (Trivers 1971). A central tenet of turning point theory is the notion that single events can prompt cognitive reconceptualization of the relationship. When an exchange encounter contrasts with the exchange partner’s understanding of the implicit rules guiding the relationship, it creates uncertainty and drives relational sensemaking, as the actor seeks to reconcile this discrepant information. Relational sensemaking is a process of organizing and interpreting relational information in search of meaning (Weick 1995). Sensemaking occurs throughout continuous relationship development, but its nature and content in discontinuous relationship development is unique, in that it begins with sensebreaking. Sensebreaking, which is “the destruction or breaking down of meaning” (Pratt 2000, p. 464), occurs when an exchange encounter challenges the presumably shared assumptions that guide the relationship and disrupts the individual’s sense of self (Planalp et al. 1988). The resulting sensemaking is grounded in identity construction and characterized by elaboration (rather than heuristic processing based on past events, as in the lifecycle perspective), such that the sensemaker attends to, analyzes, stores, and evaluates more cues (Baxter and Bullis 1986). Relational sensemaking also marks a shift in the allocation of cognitive resources, from understanding the focal transaction to analyzing the fabric of the relationship, including perceptions of past events and expectations of the future (Graham 1997). This process calls into question the previously latent relationship constructs and brings them into active consideration again (Wilson 1995). Thus, relational sensemaking can prompt an active redefinition of the underlying relational constructs, in light of a focal event. Dramatic Change in Relational Constructs A single exchange encounter can dramatically affect the development of trust, commitment, and exchange partner identification. Unexpected positive events can propel the relationship forward, by presenting the exchange partner in a state of vulnerability, revealing “true intentions”, and 16 promoting the development of trust (Jones and George 1998). Such events broaden the applicable context of trust by demonstrating the exchange partner’s intentions beyond the previously defined boundaries of the exchange. The accompanying emotional response is likely gratitude, which contributes more to the development of trust than do other positive emotions (e.g., happiness; Dunn and Schweitzer 2005). Ultimately, encounters that exceed relational expectations facilitate unconditional trust. Exchange encounters that fall below relational expectations are viewed as inconsistencies that disconfirm previous evidence collected throughout the relationship. Because a critical element of trust in an exchange relationship is the ability to predict the partner’s behavior, a single inconsistent event might send the relationship back several stages or force the partners to begin the process anew (Lewicki and Bunker 1996). When trust has developed and reached a more relational state though, disconfirming events create a sense of not knowing the partner. If this feeling cannot be overcome, trust in the relationship may be permanently destabilized (Lewicki and Bunker 1996) or transformed into distrust. Distrust implies confidence in the exchange partner’s undesirable behavior and expectations that it will not act in the exchange partner’s best interest (Lewicki, McAllister, and Bies 1998). In many relationships, negative disconfirmations would result in termination, but exchange relationships that are not easily exited must find a way to deal with the negative event. These relationships still show signs of “sentimental scars” (Dwyer et al. 1987) and are “likely to be a ‘shell’ in which only the most formal, emotionally distant, and calculative exchanges can occur” (Lewicki and Bunker 1996, p. 129). That is, a single exchange encounter can propel the relationship to a different level or create irrecoverable damage to trust. Single events also can affect commitment, whether positively or negatively (Baxter and Bullis 1986). That is, disconfirming events affect not just the decision to continue or end the relationship but also the state of commitment, because they alter the parties’ psychological and 17 behavioral (positive or negative) involvement in the relationship (Grégoire, Tripp, and Legoux 2009). Positive disconfirming events prompt an ingrained desire to reciprocate, so commitment moves beyond repeat purchases over time to include helping behaviors, such as positive word of mouth, contributions to new product developments, or premium product purchases (Palmatier et al. 2009). In other terms, positive encounters that disconfirm relational expectations create brand advocates, rather than just repeat customers (Schneider and Bowen 1999). Negative disconfirming encounters might increase active commitment to the relationship, though this relationship has taken a negative form (Grégoire et al. 2009). Exchange encounters that violate relational expectations are emotionally charged and easily recalled; the mere mention of the exchange partner then can trigger emotional memories that perpetuate a feeling of lasting hate (Grégoire et al. 2009) and motivate persistent negative actions toward the exchange partner (Schneider and Bowen 1999). Such actions might include negative word of mouth, deliberate sabotage, breach of agreements, false accusations, deterrence of future business developments, and so on (Seggie et al. 2013). Therefore, exchange encounters that disconfirm relational norms can drive dramatic relationship change, potentially producing both the most dangerous and the most valuable customers, who maintain their active (negative or positive) commitment to the partner. Finally, single events can influence exchange partner identification. Disruptive events prompt feelings of vulnerability, setting the stage for identity exploration or a reevaluation and redefinition of the partners’ roles in the relationship (McLean and Pratt 2006, p. 714). Individuals store self-defining information as life stories; events that create tension contribute more meaning to the construction of these stories (Ahuvia 2005). Encounters that negatively violate relational expectations instead threaten the exchange partner’s identity, by challenging the existing understanding of relationship roles (Ethier and Deaux 1994). However, a partner might not abandon its identity altogether but rather alter feelings about that identity, by redefining it as an undesired or 18 feared self (Markus and Nurius 1986), such as, “I used to be a customer of XYZ company, but I can’t imagine working with them again” or “I could never go back to being an XYZ customer.” In summary, turning point theories suggest that single exchange encounters can prompt social emotions, reciprocal behaviors, and cognitive sensemaking that facilitate dramatic reformulations of trust, commitment, and identification, rather than gradual changes. Integrating Lifecycle and Turning Point Perspectives While most relationship development occurs incrementally, through repeated encounters and transactions, at any point during this development, an event can spark dramatic relationship transformations. Thus, to understand when an exchange encounter incrementally builds on an existing relationship history and when an event transforms the relationship through discontinuous change, we need to integrate both lifecycle and turning point theories. The relative impact of an exchange encounter on the underlying relationship depends on the interpretation of the event, as either confirming or disconfirming relational expectations. Dynamic Relational Expectations According to lifecycle theories, relational expectations evolve as trust, commitment, and exchange partner identification change in importance and form and alter the underlying psychological contract of the relationship (Robinson et al. 1994). The constant state of transition affects the interpretation and relative importance of new information and thus the relative impact of exchange encounters. Early in the relationship, expectations of mutually beneficial behavior are low, because both parties work toward their own individual goals and only gradually shift toward a more relational state (Dwyer et al. 1987). Relational Disconfirmations: Assimilation vs. Contrast Effects Due to evolving expectations, the same behavior might confirm or disconfirm expectations, depending on the stage of development. Positive behavior in a weakly developed relationship (e.g., 19 remembering a customer’s name) may be disconfirming, but in a strong relationship, this same behavior reflects the underlying rules guiding the relationship and confirms relational expectations. Conversely, early in the relationship, expectations of autonomous behavior reinforce individual goals, so mildly opportunistic behavior (e.g., arguing over a contractual detail) likely is interpreted less severely than in mature relationships that are defined by expectations of stewardship (Macneil 1977). When relational expectations are high, suggesting stewardship and shared identity, relational disconfirmations “tap into the values that underlie the relationship and create a sense of moral violation,” thus sparking more devastating transformations (Lewicki and Bunker 1996, p. 127). Because trust is central to relational expectations, it may play an integral role in the interpretation of exchange encounters. For example, as trust evolves from calculative to relational, negative disconfirmations shift too, from signaling unpredictability to indicating moral incompatibility. Figure 2 illustrates this integration of lifecycle and turning point theories. - Insert Figure 2 about here Relationship-Building and -Recovering Strategies Lifecycle theories of relationship development guide most relationship marketing strategies in practice. However, because the underlying mechanisms, trajectories, and outcomes vary when relationships undergo discontinuous change, strategies emerging from the turning point perspective should vary. Therefore, we review strategies based on lifecycle theories of development but also highlight current strategies observed in practice that adopt a turning point perspective. Relational Strategies Based on a Lifecycle Perspective Relationship marketing strategies informed by lifecycle theories typically manifest themselves as traditional loyalty programs, which are some of the most commonly deployed relationship marketing strategies intended to build strong customer relationships. The majority of these programs reflect lifecycle theories of gradual growth through predetermined milestones. 20 Incrementally earned rewards promote habit-based loyalty by encouraging repeat transactions. Predetermined milestones associated with benefits such as exclusive discounts or priority treatment use status to reinforce loyalty (Henderson, Beck, and Palmatier 2011). Investments are typically preplanned and occur over time. Because participants expect these rewards, customer gratitude gives way to feelings of entitlement, which may reduce the effectiveness of the investment (Wetzel, Hammerschmidt, and Zablah 2014). Lifecycle theories also inform relationship recovery strategies, in terms of addressing overall levels of opportunism, conflict, and equity in the relationship. Recovery strategies typically focus on reducing negative behavior over time. Both active opportunism, which is explicitly or implicitly prohibited by relationship rules, and passive opportunism, which involves some form of withholding or evasion, can hinder relationship performance (Wathne and Heide 2000). To reduce opportunism, Wathne and Heide (2000) suggest strategies such as continual monitoring, incentive systems, careful partner selection, and socialization to establish beneficial norms of governance. High levels of relationship conflict can hinder communication, flexibility, and relational norms. Both bilateral and unilateral communication strategies can improve conflict resolution (Koza and Dant 2007). Perceived unfairness in exchange relationships not only causes relationship deterioration but also enhances the negative effects of opportunism and conflict, so it is critical to address (Samaha, Palmatier, and Dant 2011). Lifecycle-based recovery strategies for restoring equity include the use of contracts and transparent terms. Thus, lifecycle-based strategies focus on long-term investments over time to facilitate, maintain, or restore beneficial behavior in the relationship. Relational Strategies Based on a Turning Point Perspective Because of the shortcomings of traditional, incremental loyalty programs, informed by lifecycle theories (Dowling and Uncles 1997), a growing group of companies is challenging 21 traditional thinking and issuing spontaneous rewards, as illustrated effectively by Anheuser-Busch’s “Up for Whatever” campaign and its recent appointment of a vice president of experiential marketing, whose primary role is to design unexpected, positive experiences for customers (Fromm 2014). Another example, Hyatt’s Random Acts of Generosity, relies on the discretion of employees to offer unexpected rewards to customers (Walker 2009). In contrast with lifecycle-based loyalty initiatives that require consistent investments over time, turning point–based initiatives suggest a significant investment, deployed all at once. This new wave of loyalty initiatives remains poorly researched, but understanding the mechanisms and unique elements of discontinuous relationship change could help managers deploy their resources more effectively. In particular, research should specify the role of authenticity and storytelling for improving both the design and management of turning point–based strategies (Arnould and Price 1993). Turning point recovery strategies similarly address the reparation of specific, destructive acts. Because relational disconfirmations can shatter trust, promote destructive behavior, and negatively transform exchange partner identities, recovery strategies must reactively address emotion, behaviors, and cognitions. (Lewicki and Bunker 1996; p. 122) suggest that “if people believe that they can adequately explain or understand someone else’s behavior, they are willing to accept it (even if it has create costs for them), ‘forgive’ that person, and move on it the relationship.” Turning point research on redemptive stories similarly suggests that relationship talk, defined as communication among exchange partners about the underlying relationship, can help restore relationships after any particularly destructive act (McLean and Pratt 2006). Research into different types of apologies could be particularly helpful for building understanding of relationship recovery strategies following a negative relational disconfirmation. Conclusion and Further Research 22 This chapter has provided a review of research on relationship dynamics, focusing primarily on the role of exchange encounters in perpetuating either continuous or discontinuous relationship change. Exchange encounters either confirm relational expectations and prompt assimilation through demonstration, learning and negotiation, or disconfirm relational expectations and prompt contrast effects in the form of social emotions, reciprocal behaviors, and relational sensemaking. These two trajectories of relationship change have unique effects on the relational constructs, trust, commitment, and exchange partner identification. Our focus on the dynamic aspects of exchange relationships and the turning point perspective provides directions for further research. Extant research on relationship development focuses almost exclusively on measuring and quantifying overall relational variables (e.g., trust, commitment, loyalty, satisfaction, opportunism, dependence, investment), with little regard for the dynamic aspects. Although lifecycle research identifies several processes of relationship development, most of this work is conceptual. Methods such as hidden Markov models (Netzer et al. 2008), spline regression analysis, and event studies promise potential contributions to the study of developmental processes. In addition, because relationship development is essentially a study of processes, a good understanding of cause-andeffect relationships is essential. Although they are generally less frequently deployed in the study of exchange relationships (Seggie et al. 2013), experimental designs and field experiments could illuminate some of these relationships. Finally, the notion that exchange encounters drive relationship change suggests that event-level research might contribute to an overall understanding of relationship development. 23 References Ahearne, Michael, C.B. Bhattacharya, and Thomas Gruen (2005), "Antecedents and Consequences of Customer-Company Identification: Expanding the Role of Relationship Marketing," Journal of Applied Psychology, 90 (May), 574-85. Ahuvia, Aaron C. (2005), "Beyond the Extended Self: Loved Objects and Consumers Identity Narratives," Journal of Consumer Research, 32 (June), 171-84. Albert, Stuart and David A. Whetten (1985), "Organizational Identity," in Research in Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Review, Barry M. Staw and Larry L. Cummings, eds. Vol. 7. Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press. Anderson, James C. (1995), "Relationships in Business Markets: Exchange Episodes, Value Creation, and Their Empirical Assessment," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23 (Fall), 346-50. Anderson, James C. and James A. Narus (1990), "A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships," Journal of Marketing, 54 (January), 42-58. Antia, Kersi D. and Gary L. Frazier (2001), "The Severity of Contract Enforcement in Interfirm Channel Relationships," Journal of Marketing, 65 (October), 67-81. Arino, Africa and Jose De La Torre (1998), "Learning from Failure: Towards an Evolutionary Model of Collaborative Ventures," Organization Science, 9 (May-June), 306-25. Arnould, Eric J. and Linda L. Price (1993), "River Magic: Extraordinary Experience and the Extended Service Encounter," Journal of Consumer Research, 20 (June), 24-45. Baxter, Leslie A. and Connie Bullis (1986), "Turning Points in Developing Romantic Relationships," Human Communication Research, 12 (Summer), 469-93. Bitner, Mary Jo (1995), "Building Service Relationships: It's All About Promises," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23 (Fall95), 246-51. Bolton, Charles D. (1961), "Mate Selection as the Development of a Relationship," Marriage and Family Living, 23 (August), 234-40. Doney, Patricia M. and Joseph P. Cannon (1997), "An Examination of the Nature of Trust in BuyerSeller Relationships," The Journal of Marketing, 61 (April), 35-51. Dowling, Grahame R. and Mark Uncles (1997), "Do Customer Loyalty Programs Really Work?," MIT Sloan Management Review, 1 (Summer). Dunn, Jennifer R. and Maurice E. Schweitzer (2005), "Feeling and Believing: The Influence of Emotion on Trust," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88 (5), 736-48. Dwyer, F. Robert, Paul H. Schurr, and Sejo Oh (1987), "Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships," Journal of Marketing, 51 (April), 11-27. Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. and Jeffrey A. Martin (2000), "Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They?," Strategic Management Journal, 21 (Oct-Nov), 1105-21. Emmons, Robert A. and Michael E. McCullough (2004), The Psychology of Gratitude. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, USA. Ethier, Kathleen A. and Kay Deaux (1994), "Negotiating Social Identity When Contexts Change: Maintaining Identification and Responding to Threat," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67 (August), 243-51. Fromm, Jeff (2014), "The Secret to Bud Light's Millennial Marketing Success," Forbes, (10/07/2014), (accessed [available at http://www.forbes.com/sites/jefffromm/2014/10/07/the-secret-to-bud-lights-millennialmarketing-success/%5D. Ganesan, Shankar (1993), "Negotiation Strategies and the Nature of Channel Relationships," Journal of Marketing Research, 30 (May), 183-203. 24 Graham, Elizabeth E. (1997), "Turning Points and Commitment in Post-Divorce Relationships," Communications Monographs, 64 (December), 350-68. Grégoire, Yany and Robert J. Fisher (2008), "Customer Betrayal and Retaliation: When Your Best Customers Become Your Worst Enemies," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36 (March), 247-61. Grégoire, Yany, Thomas M. Tripp, and Renaud Legoux (2009), "When Customer Love Turns into Lasting Hate: The Effects of Relationship Strength and Time on Customer Revenge and Avoidance," Journal of Marketing, 73 (November), 18-32. Heide, Jan B. (1994), "Interorganizational Governance in Marketing Channels," Journal of Marketing, 58 (January), 71-85. Henderson, Connor M., Josh T. Beck, and Rober W. Palmatier (2011), "Review of the Theoretical Underpinnings of Loyalty Programs," Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21 (July), 256-76. Hibbard, Jonathan D., Nirmalya Kumar, and Louis W. Stern (2001), "Examining the Impact of Destructive Acts in Marketing Channel Relationships," Journal of Marketing Research, 38 (February), 45-61. Jap, Sandy D. and Shankar Ganesan (2000), "Control Mechanisms and the Relationship Life Cycle: Implications for Safeguarding Specific Investments and Developing Commitment," Journal of Marketing Research, 37 (May), 227-45. Jap, Sandy D. and Erin Anderson (2007), "Testing a Life-Cycle Theory of Cooperative Interorganizational Relationships: Movement across Stages and Performance," Management Science, 53 (February), 260-75. Johnson, Jean L., Ravipreet S. Sohi, and Rajdeep Grewal (2004), "The Role of Relational Knowledge Stores in Interfirm Partnering," Journal of Marketing, 68 (July), 21-36. Jones, Gareth R. and Jennifer M. George (1998), "The Experience and Evolution of Trust: Implications for Cooperation and Teamwork," Academy of Management Review, 23 (July), 531-46. Koza, Karen L. and Rajiv P. Dant (2007), "Effects of Relationship Climate, Control Mechanism, and Communications on Conflict Resolution Behavior and Performance Outcomes," Journal of Retailing, 83 (3), 279-96. Koza, Mitchell P. and Arie Y. Lewin (1998), "The Co-Evolution of Strategic Alliances," Organization Science, 9 (May-June), 255-64. Lewicki, Roy J. and Barbara B. Bunker (1996), "Developing and Maintaining Trust in Work Relationships," in Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research, Roderick M. Kramer and Tom R. Tyler, eds. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publishing. Lewicki, Roy J., Daniel J. McAllister, and Robert J. Bies (1998), "Trust and Distrust: New Relationships and Realities," Academy of Management Review, 23 (3), 438-58. Lewicki, Roy J., Edward C. Tomlinson, and Nicole Gillespie (2006), "Models of Interpersonal Trust Development: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Evidence, and Future Directions," Journal of Management, 32 (December), 991-1022. Lukas, Bryan A., G. Tomas M. Hult, and O. C. Ferrell (1996), "A Theoretical Perspective of the Antecedents and Consequences of Organizational Learning in Marketing Channels," Journal of Business Research, 36 (36), 233-44. Macneil, Ian R. (1977), "Contracts: Adjustment of Long-Term Economic Relations under Classical, Neoclassical, and Relational Contract Law," Northwestern University Law Review, 72 (6), 854-905. Markus, Hazel and Paula Nurius (1986), "Possible Selves," American Psychologist, 41 (September), 954-69. 25 Markus, Hazel and Elissa Wurf (1987), "The Dynamic Self-Concept: A Social Psychological Perspective," Annual Review of Psychology, 38 (38), 299-337. McLean, Kate C. and Michael W. Pratt (2006), "Life's Little (and Big) Lessons: Identity Statuses and Meaning-Making in the Turning Point Narratives of Emerging Adults," Developmental Psychology, 42 (4), 714-22. Morgan, Robert M. and Shelby D. Hunt (1994), "The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing," Journal of Marketing, 58 (July), 20-38. Narayandas, D. and V.K. Rangan (2004), "Building and Sustaining Buyer-Seller Relationships in Mature Industrial Markets," Journal of Marketing, 68 (July), 63-77. Nesse, Randolph M. (1990), "Evolutionary Explanations of Emotions," Human Nature, 1 (3), 26189. Netzer, Oded, James M. Lattin, and V. Srinivasan (2008), "A Hidden Markov Model of Customer Relationship Dynamics," Marketing Science, 27 (March/April), 185-204. Palmatier, Robert W., Rajiv P. Dant, Dhruv Grewal, and Kenneth R. Evans (2006), "Factors Influencing the Effectiveness of Relationship Marketing: A Meta-Analysis," Journal of Marketing, 70 (October), 136-53. Palmatier, Robert W., Mark B. Houston, Rajiv P. Dant, and Dhruv Grewal (2013), "Relationship Velocity: Toward a Theory of Relationship Dynamics," Journal of Marketing, 77 (January), 13-30. Palmatier, Robert W., Cheryl B. Jarvis, Jennifer R. Bechkoff, and Frank R. Kardes (2009), "The Role of Customer Gratitude in Relationship Marketing," Journal of Marketing, 73 (September), 1-18. Planalp, Sally, Diane K. Rutherford, and James M. Honeycutt (1988), "Events That Increase Uncertainty in Personal Relationships: Replication and Extension," Human Communication Research, 14 (Summer), 516-47. Pratt, Michael G. (2000), "The Good, the Bad, and the Ambivalent: Managing Identification among Amway Distributors," Administrative Science Quarterly, 45 (45), 456-93. Ring, Peter S. and Andrew H. Van de Ven (1994), "Developmental Processes of Cooperative Interorganizational Relationships," Academy of Management Review, 19 (1), 90-118. Robinson, Sandra L., Matthew S. Kraatz, and Denise M. Rousseau (1994), "Changing Obligations and the Psychological Contract: A Longitudinal Study," Academy of Management Journal, 37 (February), 137-52. Rousseau, Denise M., Sim B. Sitkin, Ronald S. Burt, and Colin Camerer (1998), "Not So Different after All: A Cross-Discipline View of Trust," Academy of Management Review, 23 (July), 393-404. Samaha, Stephen A., Robert W. Palmatier, and Rajiv P. Dant (2011), "Poisoning Relationships: Perceived Unfairness in Channels of Distribution," Journal of Marketing, 75 (May), 99-117. Schneider, Benjamin and David E. Bowen (1999), "Understanding Customer Delight and Outrage," Sloan Management Review, 41 (Fall), 35-45. Seggie, Steven H., David A. Griffith, and Sandy D. Jap (2013), "Passive and Active Opportunism in Interorganizational Exchange," Journal of Marketing, 77 (November), 73-90. Sheldon, M.E. (1971), "Investments and Involvements as Mechanisms Producing Commitment to the Organization," Administrative Science Quarterly, 16 (June), 143-50. Sherif, Muzafer and Carl Iver Hovland (1961), Social Judgment: Assimilation and Contrast Effects in Communication and Attitude Change. New Haven: Yale University Press. Tajfel, Henri and John C. Turner (1985), "The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior," in Political Psychology: Key Readings in Social Psychology, John T. Jost and Jim Sidanius, eds. 2nd ed. Vol. xiii. New York, NY: Psychology Press. 26 Teece, David J. (2007), "Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance," Strategic Management Journal, 28 (August), 1319. Trivers, Robert L. (1971), "The Evolution of Reciprocal Altruism," Quarterly Review of Biology, 46 (March), 35-57. Van Maanen, J. and E.H. Schein (1979), "Toward a Theory of Organizational Socialization," Research in organizational behavior, 1, 209-64. Walker, Rob (2009), "Hyatt's Random Acts of Generosity," The New York Times, (June 21, 2009), (accessed June 21, 2009), [available at]. Wathne, Kenneth H. and Jan B. Heide (2000), "Opportunism in Interfirm Relationships: Forms, Outcomes, and Solutions," Journal of Marketing, 64 (October), 36-51. Weick, Karl E. (1995), Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. Wetzel, Hauke A., Maik Hammerschmidt, and Alex R. Zablah (2014), "Gratitude Versus Entitlement: A Dual Process Model of the Profitability Implications of Customer Prioritization," Journal of Marketing, 78 (March), 1-19. Williamson, Oliver E. (1975), Markets and Hierarchies, Analysis and Antitrust Implications: A Study in the Economics of Internal Organization: Free Press. Wilson, David T. (1995), "An Integrated Model of Buyer-Seller Relationships," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23 (Fall), 335-45. 27 28 29 30 Figure*1* Managing*Relationship*Development:*Continuous*and*Discontinuous*Relationship*Change* Relationship5Building*Mechanisms* Exchange) encounter) con.irms) relational) expectations) Demonstration) Yes) Assimilation) Negotiation) Learning) No) Relationship5Transforming*Mechanisms* Positive* Contrast) Positive) • Reciprocating)behaviors)) • Gratitude) • Relational)sensemaking) Incremental** Relationship*Building* • Trust) • Commitment) • Exchange)partner) identi.ication) Dramatic** Relationship*Reformulation* Positive* • Unconditional)trust) • Active)positive) commitment) • Brand)advocate) Negative) Negative* • Punishing)behaviors)) • Betrayal) • Relational)sensemaking) Negative* • Distrust) • Active)negative) commitment) • Brand)terrorist) 31 Figure'2' Relationship'Dynamics:'Integrating'Lifecycle'and'Turning'Point'Theories' Strong'' Rela,onships' Posi,ve'discon,nuous' rela,onship'change' Nega,ve'rela,onal' disconfirma,on' Weak' Rela,onships' Posi,ve'rela,onal' disconfirma,on' Evolving'rela,onal' 'expecta,ons' (Lifecycle'perspec,ve)' Nega,ve'discon,nuous' rela,onship'change' Poor'' Rela,onships' Rela,onship'Development' 32

© Copyright 2026