Common structures for leasehold mixed use

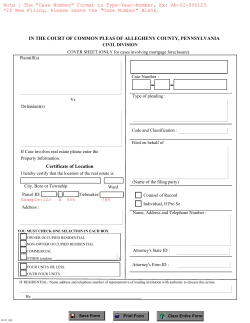

Common structures for leasehold mixed use developments Common structures for leasehold mixed use developments This practice note sets out the potential pitfalls in mixed use developments which may arise from residential leaseholders’ rights - to buy, to manage, to enfranchise and to require an extended lease - and examines the common structures used to mitigate the effects of such rights. Residential floor space less than 50% of the total floor area in the scheme (excluding common parts) Residential floor space more than 50% but less than 75% (excluding common parts) Residential floor space more than 75% (excluding common parts) yes yes yes No: right to manage, right to buy, right to enfranchise Right to extended lease applies No structure mechanism required No: right to manage or right to enfranchise Right to extend lease and right to buy apply Structure: buffer lease required of residential element Right to manage, enfranchise, buy and extend apply Structure: buffer lease required of residential element and /or commercial element Why is structuring a mixed use scheme important? Mixed use developments are schemes which comprise one or more buildings used for commercial, retail and/or industrial use where there is also an element of residential accommodation. Even where the residential element is ancillary to the main commercial use, these schemes need to be treated with a certain degree of caution. Common pitfalls and challenges include: Right to buy Rights of pre-emption pursuant to the Landlord and Tenant Act 1987 (1987 Act) give qualifying long lease residential tenants the right of first refusal to purchase the immediate reversion to their leases. A landlord wishing to dispose of the reversion must first offer it to such tenants, who then have two months to exercise their rights. Failing to comply with the requirements of the 1987 Act is a criminal offence. See further practice note: Landlord and Tenant Act 1987 – tenants’ right of first refusal Right to enfranchise The Leasehold Reform, Housing and Urban Development Act 1993 (LRHUDA 1993) gives occupiers of long residential leases (more than 21 years) the collective right to buy the freehold and any intermediate leasehold interest where the residential floor areas account for over 75 percent of the whole development (not including common parts). In a mixed use development where there are service charge contributions or commercial rental income streams, the collapsing of superior leasehold interests could result in the obligation to contribute to service charge falling away or the potential loss of the commercial rental income by the leasehold reversioner. See further practice note: The collective right to enfranchise Lease extension Rather than act collectively, individual tenants in a leasehold building may exercise the right under LRHUDA 1993 to be granted a further 90 year lease- whilst the immediate landlord is paid a commuted sum in respect of lost ground rent. If there are a significant number of leasehold extensions this may seriously erode the value of a ground rent portfolio. See further practice note: The right to an extended lease – flats Right to manage In circumstances where residential units form more than 75 percent of the overall floor area (and on certain other conditions being fulfilled) residential tenants may collectively exercise rights under LRHUDA 1993 to take over the management of the scheme, by forming a Right to Manage (RTM) company. Where there are commercial elements in the building, the RTM company can require the landlord to contribute to the service charge it levies for the building. This will be bad news for landlords who agreed to cap commercial service charges on the basis that they controlled the services. The landlord may also lose control over the building insurance since RTMs are also required to insure. The landlord’s ability to recover insurance rent from commercial tenants may also be impaired. See further practice note: The right to manage Service charge issues Different regulatory and common law principles apply to the recovery of service charges in commercial and residential developments. Residential service and administrative charges are heavily regulated and impose additional preconditions to and limitations on their recovery. By contrast, commercial service charges are relatively free from direct statutory constraint. In a mixed use development it is often difficult to separate and avoid any overlap of the commercial and residential service charge regimes. In such cases, the landlord may have difficulty recovering service charge expenditure in full. See further practice notes: Commercial service charges – what expenses can the landlord recover? Commercial service charges – the importance of following procedures Residential – code for residential service charges Residential – statutory consultation procedure for service charges Residential – statutory limitations on recovery of service charges and administration charges 3 Common structures Careful forward planning and structuring of mixed use developments can mitigate the effect of the above rights. Three common structures are used for buildings mixing long residential leases and shorter rack rent commercial leases. The choice of structure will largely depend on the freeholder/developer’s primary objectives i.e. whether it wants to receive capital or income; and when (or if) it wants to exit the scheme at the end of the development. A common tool in leasehold structures is to interpose “buffer” or “blocking” leases between the residential leases and the freehold enabling the freehold to be sold without triggering the right to buy under the 1987 Act. Model A- simple developer capital receipt model Figure 1 Freeholder Rent/service charge/ insurance Rent/service charge/ insurance Commercial Tenant Residential Tenant 4 Model A- simple developer capital receipt model Figure 1 This model does not make use of any buffer leases between the freeholder/developer and the residential and commercial long leaseholders. A classic example would be the development of a single mixed use block with commercial space on the ground floor and flats above. Prior to entering any sale agreement for residential units, the developer enters into an agreement for lease or long lease of the commercial space. As a result the completion of the commercial leases will not trigger the right to buy under the 1987 Act. The developer then provides the commercial and residential services and insures the building and in return receives the service charge; ground rent; and insurance rent. This model is best suited to simpler, smaller developments, where: i) the developer’s main objective is to extract capital profit on the sale of individual residential and commercial units on long leases; and ii) the developer has no intention of selling the reversion and is not concerned about remaining responsible for the management of the scheme. The freeholder/developer is left with a nominal ground rental income and the reversion will have minimal value. Potential drawbacks of this model are: • If the residential element of the scheme is more than 75 percent, residential leaseholders may exercise the right to manage or the right to collectively enfranchise. This may not be that great a concern to a freeholder/developer who has already extracted its profit. In this case the cost of implementing and maintaining any buffer structure outweighs the potential benefit of protecting a freehold with minimal residual value. • 1987 Act, s5 If the freeholder/developer decides to sell the freehold reversion this will trigger the residential leaseholders’ right to buy under the 1987 Act and the developer will need to serve notice under 1987 Act, s5 before selling. Again, as the residential leaseholders would have to match the offer price for the freehold, the freeholder/developer may stand to lose very little other than the time and cost of serving the section 5 notices. As an alternative, if the freeholder/developer is a corporate entity it may circumvent the 1987 Act by selling its shares as a corporate transaction. Model A- simple developer capital receipt model “This model is best suited to smaller simple developments where the developer’s main objective is to extract its capital profit on the sale of the individual residential and commercialunits on long leases and has no intentionof selling the reversion and no concern about remaining responsible for the management of the scheme.” • the freeholder/developer will remain responsible for managing the scheme, providing the services and collecting ground and insurance rent. Often in this sort of scheme, the freeholder/developer will contract with a specialist management company to provide the services and manage the buildings on its behalf. In this case, it is important to ensure that the leases allow the freeholder/developer either to provide or to procure the services; and to charge or pay a management fee as part of the service charge. • if the freeholder/developer decides to retain the rack rental income stream from the commercial units then, as the usual term for secured commercial lettings range between 15 and 25 years, when the commercial lease expires the developer will need to consider whether the grant of an extended or new commercial rack rent lease will trigger the 1987 Act right to buy if the commercial floor area is less than 50 percent of the total floor area in the scheme. 5 Variation to Model A - using a management company Figure 2 Ground rent and insurance Freeholder Service charge contribution Service charge and insurance Rack rent Commercial Tenant Service charge and insurance Residential Tenant Residential Management Co Ground rent Services As a variation to Model A, the freeholder/developer may contract with a specialist management company to provide the residential services. In this case the developer will want to join the management company in to the residential long leases to covenant to provide the residential services. The freeholder/developer can either provide the commercial services itself or require the management company to provide those services too. The freeholder/developer will collect the commercial service charge; rack rent; and insurance rent. The management company will collect the residential service charge; insurance rent; and ground rent, passing the ground rent and insurance rent to the freeholder/developer. The freeholder/developer will pass on the commercial service charge to the management company. 6 Model B clean freehold investment Figure 3 Model B - clean freehold investment Freeholder Rent Rent Management Co/Group Lease Rent Services Commercial Tenant Service charge Services Rent Residential Tenant This model aims to create a buffer lease between the freehold reversion and the long residential leases in order to achieve a clean investment freehold with minimal responsibilities for management of the scheme. This model is often used in larger developments where the freehold developer wants to receive both capital and income. The essentials of this structure are: “This model aims to create a buffer lease between the freehold reversion and the long residential leases in order to achieve a clean investment freehold with minimal responsibilities for management of the scheme. This model is often used in larger developments where the freehold developer wants to receive both capital and income.” freehold developer and management / group company • An agrement for lease of the whole of the scheme including the commercial element is granted to a management or group company before two or more residential units come into existence or (if already in existence), before any sale agreements have been entered into for two or more residential units • the lease to the management company is completed upon the later of: i) the transfer of the last residential unit in the scheme; and ii) completion of the last commercial lease. The freeholder/developer may retain a golden share in the management company until completion of the lease to the management company enabling it to direct and control management of the scheme notwithstanding its diminishing interest in it. • the lease to the management company obliges it to provide the services, collect insurance rent, ground rent, rack rent and service charge and to pass the ground rent, rack rent and insurance rent up to the freeholder/developer . Both the freeholder/developer and the management company will have an insurable interest and either may assume responsiblitity for reinstatement. However, the freeholder/developer will typically want to control reinstatement and would therefore elect to insure, with insurance rent being passed up to it by the management company. • the benefit of this structure is that it creates a clean freehold investment with a buffer lease between the freehold and the residential units enabling the freeholder to hold or sell the freehold with the ground rent and rack rent income as an investment. The freeholder/developer is not responsible for the management of the scheme. On subsequent sales of the freehold investment, there is no need to serve notices offering the freehold to the residential leaseholders. A potential disadvantage is that the freeholder/developer loses direct control over the commercial unit(s) and related income. The lease to the management company may however include consultation and consent provisions in relation to certain issues e.g. rent reviews, re-lettings and the approval of commercial tenants. 7 Variation to Model B - Freehold developer with management / group company and separate commercial element Figure 4 Freeholder/Developer/ Investor Rent Service Charge Commercial Tenant Services Rent Service Charge Contribution Management Co./ Group Company Lease Services Rent Residential Tenant A variation to model B is for the freeholder/developer to carve out the internal demise of the commercial units from the management lease and to retain direct control of the commercial premises. Depending on the layout of the scheme, the management lease could either require the management company to provide the services to the whole of the scheme or keep the provision of the commercial services separate to be administered by the freeholder/developer. In the first case, the management company is likely to require the freeholder to contribute to the service charge for the commercial premises and the freeholder would recharge this to the commercial tenants. Depending on the scale of the commercial development, non-recovery of service charge from commercial tenants may pose a risk to the freeholder/developer . In the second case, the freeholder/developer would remain responsible for the provision of services to the commercial units which might detract from it being a pure investment model. There may also be a residual service charge payment to the management company as a contribution to the maintenance of common structures and facilities. The disadvantages of both of these structures is that where the residential element is 75 percent or more of the scheme, residential tenants could exercise the right to manage or the right enfranchise which could result in the freeholder/developer losing the income from the rack rent commercial lease unless it counters the claim for enfanchisement by serving a counter-notice requesting a leaseback of the commercial space or setting up the scheme initially with a separate commercial buffer lease in place from the outset. See further practice note: Collective enfranchisement—the counter notice and precedent Reversioner’s counter-notice 8 Model C - SPV Management Company (no buffer lease) Model C- SPV management company - no buffer lease Figure 5 Freeholder (SPV) Shares Shares Services Service Charge Commercial Tenant Services Residential Tenant This model makes no use of any buffer leases. It may be used for more complex developments but is not always popular with residential tenants as it involves the requirement for them to hold shares in the management company and be involved in its management. It is favoured by developers who want the capital receipts from the sale of units but no income. This model makes no use of buffer leases. It may be used for more complex developments but is not always popular with residential tenants as it requires them to hold shares in the management company and be involved in its management. It is favoured by developers who want the capital receipts from the sale of units but no income. In its basic form, the developer will transfer the freehold into a special purpose vehicle (SPV) which will either be limited by shares but more commonly, limited by guarantee (which has fewer corporate governance requirements) with the appropriate articles and memorandum from the start. The SPV will grant the leases of the units and each leasehold owner will be required to take a share in the SPV along with its long leasehold interest. The developer will hold a golden share in the SPV until the sale of the last unit in the scheme, thereby retaining control over its management until such time as the developer has sold all of the units. The owners of the leasehold units will be responsible for the management of the scheme by way of the SPV which will also own the freehold. The developer will exit the scheme once it has sold all the units and have no further interest in it nor will it receive any ground rent. See precedents: Memorandum of association--tenants’ management company limited by shares Articles of association--tenant’s management company limited by shares Memorandum of association--tenants’ management company limited by guarantee Articles of association--tenant’s management company limited by guarantee 9 Variation to Model C - SPV management company- ground rent model Figure 6 Freeholder Rent Rent Management Co/ Group Lease Rent Services Commercial Tenant Service charge Services Rent Residential Tenant A variation on Model C may be used where the freeholder/developer wants to receive ground rent. The freeholder/developer acquires the freehold and immediately puts in place an agreement for lease with the management SPV which is controlled by the freeholder/developer . The agreement for lease or lease of the commercial element needs to be put in place before any residential units are sold, or a separate commercial buffer lease (or agreement) put in place similar to the variation to Model B. The freehold developer will require the management SPV (or SPVs) to pass up ground rent to it. To mitigate against the right to extend leases, the management SPV lease(s) could be granted for 999 years or if granted for a lesser term, include the right to renew. For a Precedent concurrent lease to a tenants’ management company see: Concurrent lease to Management Company. 10 Further reading/information We hope you’ve enjoyed this Guide to Common Structures for Leasehold Mixed Use Developments. This Guide mentioned a number of relevant Practice Notes and Precedents and these are listed again below, together with information on other products and sources of information you might find useful. Practice Notes referred to in this Guide (Subscribers Only) LexisPSL Property – why not try it out? Landlord and Tenant Act 1987 – tenants’ right of first refusal LexisPSL Property brings all of the different sources you need together so you can find the answers you need, fast. Our succinct practice notes are designed to be read in six minutes or less. They’re full of practical hints and tips from practising property lawyers (who understand what you need to know and do, because they’ve been in your position before). With direct links for deeper research, you can dive straight in to the relevant cases and consolidated legislation (including Butterworths Property Law Handbook, Ross Commercial Leases, Hillman and Redman’s Law of Landlord and Tenant and everything in Lexis®Library). Regular news reports let you stay on top of what’s happening in the law and the industry. The collective right to enfranchise The right to an extended lease – flats Exercising the collective right to enfranchise - leasebacks Collective enfranchisement – the counter notice The Right to Manage Commercial service charges – what expenses can the landlord recover? Commercial service charges – the importance of following procedures Take a FREE TRIAL: lexisnexis.co.uk/mixeduse/freetrial Residential – code for residential service charges Residential – statutory consultation procedure for service charges Free Content Residential – statutory limitations on recovery of service charges and administration charges For regular FREE content from the LexisPSL Property team and guest contributors visit “Purpose Built”, the LexisNexis blog about the Built Environment. Precedents referred to in this Guide (Subscribers Only) Visit the blog: lexisnexis.co.uk/mixeduse/purposebuilt Memorandum of association--tenants’ management company limited by shares Articles of association--tenant’s management company limited by shares Memorandum of association--tenants’ management company limited by guarantee Articles of association--tenant’s management company limited by guarantee Agreement for sale or lease to a Management Company. Concurrent lease to Management Company. Reversioner’s Counter Notice (to claim for enfranchisement) Reed Elsevier (UK) Limited trading as LexisNexis. Registered office 1-3 Strand London WC2N 5JR Registered in England number 2746621 VAT Registered No. GB 730 8595 20. LexisNexis and the Knowledge Burst logo are trademarks of Reed Elsevier Properties Inc. © LexisNexis 2014 1214-007. The information in this brochure is current as of March 2015 and is subject to change without notice.

© Copyright 2026