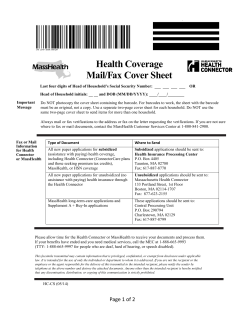

coverage options for massachusetts: leveraging the affordable care act