The University of Chicago

The University of Chicago Temperature, Activity, and Lizard Life Histories Author(s): Stephen C. Adolph and Warren P. Porter Source: The American Naturalist, Vol. 142, No. 2 (Aug., 1993), pp. 273-295 Published by: The University of Chicago Press for The American Society of Naturalists Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2462816 . Accessed: 05/09/2013 17:33 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. . The University of Chicago Press, The American Society of Naturalists, The University of Chicago are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Naturalist. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions The AmericanNaturalist Vol. 142, No. 2 August 1993 TEMPERATURE, ACTIVITY, AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES STEPHEN C. ADOLPH AND WARREN P. PORTER Departmentof Zoology, Universityof Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin53706 SubmittedDecember 23, 1991; Revised June 8, 1992; Accepted July10, 1992 characteristicsvarywidelyamongspecies and populations.Most Abstract.-Lizard life-history patterns,which are usually authorsseek adaptive or phylogeneticexplanationsforlife-history presumedto reflectgeneticdifferences.However, lizard lifehistoriesare oftenphenotypically factors. plastic, varyingin response to temperature,food availability,and otherenvironmental Despite the importanceof temperatureto lizard ecology and physiology,its effectson life historieshave received relativelylittleattention.We presenta theoreticalmodel predictingthe proximateconsequences of the thermalenvironmentfor lizard life histories.Temperature,by affectingactivitytimes, can cause variationin annual survivalrate and fecundity,leading to a thermal negativecorrelationbetween survivalrate and fecundityamongpopulationsin different environments.Thus, physiologicaland evolutionarymodels predictthe same qualitativepattern data from variationin lizards. We tested our model with published life-history of life-history fieldstudies of the lizard Sceloporus undulatus,using climate and geographicaldata to reconstructestimatedannual activityseasons. Amongpopulations,annual activitytimeswere negatively correlated with annual survival rate and positively correlated with annual fecundity. variaProximateeffectsof temperaturemay confoundcomparativeanalyses oflizardlife-history tion and should be included in futureevolutionarymodels. characteristics varywidelyamonglizardspeciesand populations Life-history (Tinkle1967,1969;Fitch1970;Ballinger1983;Stearns1984;Dunhamand Miles mostauthorssoughtadaptiveexplanations 1985;Dunhamet al. 1988).Initially, on thebasis ofpredictions fromlife-history theory forlizardlife-history patterns (Tinkle1969;Tinkleet al. 1970;TinkleandBallinger1972;Stearns1977;Ballinger 1979;Tinkleand Dunham1986;Dunhamet al. 1988).A second,morerecent underlievariationin life approachexamineshow body size and/orphylogeny histories(Ballinger1983;Stearns1984;Dunhamand Miles 1985;Dunhamet al. assumethat 1988;Miles and Dunham1992).These approachesoftenimplicitly variation based. However,commongardenexperiments is genetically life-history onlya fewtimeswithlizards(Tinkle (Clausenet al. 1940)have been performed 1970;Ballinger1979;Fergusonand Brockman1980;Sinervoand Adolph1989; Sinervo1990;Fergusonand Talent 1993).Therefore, we knowlittleaboutthe eitheramongorwithinspecies(Stearns1977; geneticbasisoflizardlifehistories, Ballinger1979,1983;Fergusonet al. 1980;Bradshaw1986;Sinervoand Adolph by a number in naturalpopulationsare affected phenotypes 1989).Life-history of environmental factors(Bervenet al. 1979;Ballinger1983;Bervenand Gill and moistureare knownto foodavailability, temperature, 1983).In particular, exertproximate on lizardlifehistories(Tinkle1972;Ballinger1977, influences Am. Nat. 1993. Vol. 142, pp. 273-295. ? 1993 by The Universityof Chicago. 0003-0147/93/4202-0005$02.00. All rightsreserved. This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE AMERICAN NATURALIST 274 | Tpreferred .... ............. (inactive) -a-- active - P . ..................... .W... (inactive) TIME OF DAY FIG. 1.-Idealized daily body temperature(Tb) profileof a diurnal,heliothermiclizard. Value of Tb is typicallyhighand relativelyconstant(around Tpreferred) duringactivitybecause The Tb value of active lizardsoftenvariesrelativelylittleover thecourse ofthermoregulation. environments.However, the of the activityseason and among populationslivingin different and therefore amountof timelizards can attainTpreferred depends on the thermalenvironment can vary substantiallyboth seasonally and geographically.In addition,Tb of inactivelizards is likelyto vary seasonally and geographically. 1983;Dunham1978,1981;Abts1987;JonesandBallinger1987;Joneset al. 1987; Sinervoand Adolph1989;Sinervo1990). to lizard ecology and physiology Despite the importanceof temperature (Cowles and Bogert1944; Bartlettand Gates 1967;Norris1967;Avery1979; havereceivedlittleformalattention until Huey 1982),itseffectson lifehistories recently(Huey and Stevenson1979; Ballinger1983;Nagy 1983;Beuchatand Ellner1987;Jonesand Ballinger1987;Joneset al. 1987;Dunhamet al. 1989; Porter1989;Sinervoand Adolph1989;Sinervo1990;Grantand Dunham1990; can Grantand Porter1992).In thisarticlewe discussthewaysthattemperature lizardlifehistories.We presenta generalmechanistic modelforthe influence oftemperature on fecundity and survivalrate,based on lizard proximate effects thermalphysiology.Specifically, we addressthe question:Whatkindof lifethermalenvironments historyvariationwould we expect to see among different due simplyto proximate effectsin theabsenceof geneticdifferentiation among feaOur modelpredictsthe same associationbetweenlife-history populations? turesthatis predicted different by evolutionary theories,butbecauseofentirely causes. We thenprovidea testof our modelusingpublisheddata frompopulationsof theeasternfencelizard,Sceloporusundulatus.Finally,we discussthe limitations ofourmodel,itsimplications forlife-history evolution, anditsimplicawillrespondto climatechange. tionsforhowpopulations TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES: POSSIBLE MECHANISMS on lizardlifehistories oftemperature is complicated The effect bythefactthat Diurnallizardsoftenmaintaina relatively high, manylizardsthermoregulate. constantbody temperature(Tb) duringdaytimeactivity(fig. 1) throughvarious behavioraland physiologicalmechanisms(Cowles and Bogert 1944; Avery 1979, This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions AND LIZARDLIFE HISTORIES TEMPERATURE 275 1982;Huey 1982;Bradshaw1986).As a result,themeanTbofactivelizardsoften littledespitedaily,seasonal,andgeographical variesrelatively variation inthermal environments (Bogert1949;Avery1982).However,twoaspectsoflizardTbare environments and seasonallyin thesameenvironlikelyto varyamongdifferent is largelydetermined ment(fig.1). First,Tbduringinactivity bysubstrate andair whichrestricts temperatures, thermoregulatory options(butsee Cowlesand Bogert1944;Porteret al. 1973;Huey 1982;Huey et al. 1989).Second,and more theamountoftimeperdaythata lizardcan be activeat itspreferred important, environment and Gates 1967;Porteret Tbis constrained by thethermal (Bartlett et al. 1983;Porterand Tracy al. 1973;Huey et al. 1977;Avery1979;Christian 1983;Grantand Dunham1988,1990;Sinervoand Adolph1989;Van Dammeet timeof activityis one of theprimary al. 1989).Indeed,modifying mechanisms by whichlizardsthermoregulate (Huey et al. 1977;Grantand Dunham1988). environments Thus, althoughlizardsin two different mightmaintainthe same meanTbduringactivity,thecumulativeamountof timespentat highTbcould Annualactivitytimeis thenroughly differ substantially. equivalentto thetotal amountoftimespentat highTbandcan be considereda measureofphysiological timeforlizards. Lizards are foundin a wide varietyof thermalenvironments, hot including tropicallowlands,temperate deserts,and cool, highlyseasonalhabitatsat high in thermal elevationor highlatitude(Pearsonand Bradford1976).Thisvariation inactivity variation andconcomitant season(Huey 1982),is likely environments, inlifehistories tocause someoftheobservedvariation amongspeciesandamong widespreadpopulationsof singlespecies (Grantand Dunham1990).Here, we can directlyinfluence describesome of the ways thattemperature life-history characteristics. Many of theseeffectsare mediatedthrough activitytimesand energybudgets. ActivityTime and Energetics Energyallocatedto reproduction ultimately dependson thedailyenergybudget,whichin turndependson activitytimein severalways.Energyacquisition and by therate bothby therateat whichresourcesare harvested is determined at whichtheyare processed(Congdon1989).Daily preycapturerate should thatlizardsare foraging increasewithdailyactivitytime,undertheassumption whileactive(Avery1971,1978,1984;Averyet al. 1982;Karasovand Anderson et al. 1986).In addition,highTbmayincreasepreycapture 1984;Waldschmidt ratesand handling efficiency (Averyet al. 1982;Van Dammeet al. 1991).Daily shouldincreasewithactivity energyassimilation time,becauseratesofdigestion are temperature at ornearactivity andassimilation andaremaximized dependent and Louw Tb's(Avery1973,1984;Skoczylas1978;Harwood1979;Buffenstein 1982;Huey1982;Waldschmidt etal. 1986,1987;Dunhametal. 1989;Zimmerman andTracy1989;Van Dammeet al. 1991).On thedebitsideoftheenergybudget, shouldalso increasewithactivitytime,bothbecause dailyenergyexpenditure resting metabolicratesare higherat activityTb's(BennettandDawson 1976)and because activelizardsoftenincuradditionalmetaboliccosts in pursuingprey, and the like (Bennett1982;Karasov and Anderson1984; defending territories, This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 276 THE AMERICANNATURALIST Marlerand Moore 1989).The difference betweenenergyassimilated and energy expendedrepresents discretionary energythatcan be allocatedto reproduction, growth, or storage(Porter1989).Thus,energyallocatedto reproduction depends on activity timevia dailyandannualenergybudgets(Congdonetal. 1982;Anderson and Karasov 1988;Dunhamet al. 1989;Porter1989;Grantand Porter1992). Potential timeis likelyto be correlated activity withthesize oftheannualenergy budgetand consequently withthe amountof energythatcan be allocatedto reproduction. Growth,ActivityTime, and Age at Maturity distorts therelationship betweenphysiological In ectotherms, and temperature time(Taylor1981;Sinervoand Doyle 1990).For example,lizards chronological seasonsspendmoretimeathighTbandtherefore withlongeractivity areexpected at a youngerage (Pianka1970; to growfasterand reachreproductive maturity are supported Jamesand Shine1988).Thesepredictions byfieldstudiesshowing ratesoflizardsincreasewithannualactivity time(Davis 1967; thatannualgrowth Tinkle1972;Ballinger1983;GrantandDunham1990)andbydirectobservations underlongergrowingseasons (Tinkleand Ballinger1972; of earliermaturation Goldberg1974;Grantand Dunham1990).In addition,severallaboratory studies ofactivity timeon growth effects havedemonstrated rates.GrowthratesofjuvenileLacerta vivipara,Sceloporus occidentalis,and Sceloporus graciosus increase withdailyactivitytime(i.e., access to highTb via radiantheat; Avery1984; Sinervoand Adolph1989;Sinervo1990;B. Sinervoand S. C. Adolph,unpubis frequently observedin animalsmaintained lisheddata). Acceleratedmaturity underoptimalthermalconditionsin thelaboratory (e.g., A. Muth,unpublished data,citedin Porterand Tracy1983;Fergusonand Talent1993).The observed effects oftemperature and activity timeon growth fromtheenerfollowdirectly outlinedabove. geticconsiderations ReproductiveCycles Temperature typicallyservesas a proximatecue forinitiating reproductive cycles in temperate-zone lizards,eitherdirectlyor by entraining endogenous circannualrhythms (Duvall et al. 1982;Marion1982;Licht 1984;Mooreet al. 1984; Underwood1992). Correspondingly, populationsin warmenvironments ofteninitiate at an earlierdate(Fitch oraltitudes) (e.g.,lowlatitudes reproduction can often 1970;Goldberg1974;Duvall et al. 1982;Licht1984)and consequently reproducemorethanonce per year,whereascool environments usuallylimit to one clutchor broodper year(McCoy and Hoddenbach1966; reproduction Tinkle1969;Goldberg1974;Parkerand Pianka 1975;Gregory1982;Ballinger 1983;Joneset al. 1987;Jamesand Shine1988). ActivitySeason and SurvivalRate orlatitudes oftenhavehigher at highaltitudes annualsurvivalrates Populations at to those low altitudes/latitudes compared (Tinkle1969;Pianka 1970;Tinkle andBallinger1972;Smithand Hall 1974;Turner1977;Ballinger1979;Jamesand risk(notablyriskofpredation) is higher Shine1988).Thisimpliesthatmortality This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES 277 foractivelizardsthanforinactiveones (Rose 1981).Severalstudieswithin populationssupportthisconclusion.Wilson(1991; B. Wilson,personalcommunication)foundthatdailymortality ratesin Uta stansburianaare highestin spring, intermediate in summer, and lowestduringthewinter;dailyactivity timesfollow thesamerankorder.Marlerand Moore(1988,1989)experimentally manipulated testosteronelevels in male Sceloporus jarrovi and found that individualswith testosterone implants hadlongerdailyactivity periodsandsuffered higher mortalityrelativeto controls. Acute Effectsof Temperatureon SurvivalRates All lizards have upper and lower criticalthermallimitsbeyond which the animals perish (Cowles and Bogert 1944; Dawson 1967; Spellerberg 1973). How oftentheselimitsare approachedin natureis unknown.Deaths due to winter coldhavebeenreported (Tinkle1967;Vitt1974;reviewinGregory1982);deaths are probablyless common(Dawson 1967).Acuteeffectsof due to overheating temperature may also influencesurvivalrates indirectly, throughthe thermal andTracy1981;Huey 1982; dependenceoflocomotion(Bennett1980;Christian vanBerkum1986,1988).In somecases lizardsareactiveat Tb'sthatsignificantly impairsprintspeed, which could lead to greaterriskof predation(Christianand Tracy 1981;Huey 1982; Crowley1985;van Berkum1986;Van Dammeet al. thatlead to lowersprintspeeds 1989,1990).However,the cool environments theoveralleffect mayalso reduceactivity times,whichwouldtendto ameliorate on annualsurvivalrates.Temperature mayalso affectresistanceto disease. For example, the abilityof desertiguanas (Dipsosaurus dorsalis) to survivebacterial infectionimproveswithincreasingTb(Kluger 1979). Energetics of Hibernation Lizards can be inactive more than halfthe year, particularlyat highlatitudes or highaltitudes(Gregory1982; Tsuji 1988a). Duringthistimetheyrelyon stored energy, particularly lipids(Derickson1976;Gregory1982).Because temperature conditions affectmetabolicrates(Bennettand Dawson 1976; duringhibernation Tsuji 1988a,1988b),energystoresmustbe adequateforboththedurationand theTb'sexperienced duringhibernation. Temperatureand EmbryonicDevelopment affects In lizards,temperature and(insome eggincubation time,eggmortality, species)sexualdifferentiation (Bull 1980;Muth1980;PackardandPackard1988). shorter In warmerenvironments, incubation timesmaylengthen theactivity seathemto reacha largersize priorto son experiencedby hatchlings, permitting hibernation.Laying several clutches of eggs in a single activityseason is more incubation times.The significance oftemperafeasibleifaccompaniedby shorter forlizardlifehistories sex determination is notwellunderstood. ture-dependent inducedcorrelation One possibleeffectis an environmentally betweenhatching dateand sex, whichcouldlead to a correlation betweenjuvenilesize and sex by theend of theactivityseason. Because mostlizardsreachmaturity within1-2 couldpersistintoadulthood. yr,thissexualsize difference This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions DAY OF ACTIVITYSEASON, j a 24 . -150 -50 -100 50 0 100 150 18 O 120 b J F M A J FMAMJ J F M M J J A S O N D 24 a 24 ~18 0 6_ 0 JASMN D 24 c ~18 0 0 A M J J A SON MONTH D FIG. 2.-Seasonal variationin potentialactivitytimeof diurnallizards, as determinedby thethermalenvironmentand thermalphysiologyof thelizard. NorthernHemisphereseasons are illustrated.Unshaded region indicates times when thermalconditionspermitactivity; shaded region indicates periods of inactivity.Individuallizards may not be active as often as the thermalenvironmentpermits(see, e.g., Nagy 1973; Porteret al. 1973; Simon and Middendorf1976; Rose 1981; Beuchat 1989). a, Elliptical activityseason characteristicof manydiurnaltemperate-zonelizards. b, Activitypatternoftenobserved in lizards livingin desertsor otherseasonally hot environments,where highsummertemperaturescause midday inactivity(hence bimodal activity;Porteret al. 1973; Grant 1990; Grant and Dunham 1990). c, Rectangularactivityseason characteristicof some lowland tropicallizards (see, e.g., Heatwole et al. 1969; Porterand James 1979). This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions AND LIZARDLIFE HISTORIES TEMPERATURE 279 Thus,temperature potentially affects lizardlifehistories through variousmechanisms.However,thereis no generaltheoryincorporating theseproximate influences.A fewstudieshaveexaminedtheeffect oftemperature on lifehistories of individual detailedphysiological speciesthrough modelstailoredtothelifehistory of the species in question(Beuchatand Ellner 1987;Grantand Porter1992). Here,we presenta generalmodeloftheeffect oftemperature on annualfecundity and annualsurvivalrates.Othertraits,suchas age and size at maturity, could be modeledsimilarly. A GENERAL MODEL Annual and Daily ActivityTime For mostdiurnaltemperate-zone lizards,potentialdailyactivitytimevaries timesare typically shortin thespringandfallandlong seasonally.Daily activity insummer, becauseofseasonalchangesintemperature (Porteret al. 1973;Porter theannualactivity andTracy1983}.Here, we approximate patternas an ellipse (fig.2a), wherethe lengthof the activityseason is 2y d and the lengthof the maximumactivityday is 2d h. For an ellipticalactivityseason the potential numberofhoursofactivity perdayis givenby h = 2d/ 1-_(j2/y2), (1) wherej represents day of theyear;j = 0 at themiddleof theactivityseason, whenh is maximal.The area of theellipseTryd equals thecumulative potential hoursofactivity peryear. effectson potentialactivitytimeare reflected Temperature in thevaluesofy and d. These valuesare affected in air primarily by dailyand seasonalvariation and solarradiation.Warmlow-latitude temperature environments usuallypermit inlargey,whereaslizardsat highlatitudes formuchoftheyear,resulting activity or altitudescan have activityseasonsas shortas 4-5 mo (Tsuji 1988a).Factors and cloud cover can also affectthesevalues; heavy such as habitatstructure wouldtendto decreased becauseoftheshadowscastinearlymorning vegetation Thermalphysiological andlateafternoon. characteristics ofthelizardalso influencey andd. For example,somespeciesrequirerelatively hightemperatures for theirpotentialactivitytime(reducingbothy and whichwouldrestrict activity, thermal allowslongeractivity d). Conversely, relaxing requirements periods(PorterandTracy1983;Grant1990). fordifferent Shapes otherthanellipsesmightbe moreappropriate thermal For example,desertlizardsoftenhavebimodaldailyactivity environments. patternsduringthesummer,to avoid hotmiddaytemperatures (Porteret al. 1973; Grant1990;Grantand Dunham1990;fig.2b). Lizardsin tropicallowlandsmay be activeyear-round duringdaylighthours(Heatwoleet al. 1969;Porterand we willrestrict James1979;Huey 1982;fig.2c). For simplicity, ouranalysisto elliptical activity seasons,butourmodelcan be extendedto anyseasonalactivity pattern. This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE AMERICAN NATURALIST 280 b a ma: 1.0 0.8: 1.0 0.0001 0.60 ir 0 0.8 0.4 0 activity 0.2' cn 0.0003 0OU 0.3 0.6 0.6 e.(.uvartce0.0005s saneg(uutehroatiyafr _1 m z [lotte on z 0.1030006 FIG. 1000 0.0 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 0m00vm6 00i00o3aeSa nulautsria La,3.Mdlpeitosfrepce 0.05 0.4 2000 0.2 3000 10~00 2000 uciono 0.00009 3000 ANNUALACTIVITYTIME(HOURS) ANNUALACTIVITYTIME(HOURS) of FIG. 3.-Model predictions forexpectedannualadultsurvivalrateS as a function seasonlength(cumulative hoursof activity, a), fromeq. (3). Survivalratecurves activity are plottedon a logarithmic scale forseveraldifferent values Of Ma and mi (thehourly and inactivity, valuesof risksduringactivity a, Effectofdifferent mortality respectively), valuesofini, setting ofdifferent Ma equal to 0.0003. in'al setting miequal to 0; b, effect SurvivalRates We assumethateach individual has constantprobabilities ofmortalityMaper oftimeofyearortime andmiperhourofinactivity, independent hourofactivity amongindividuofday.Undertheassumption thatmortality riskis independent is givenby als, expectedannualsurvivalrate(S) forthepopulation S = (1 - ma)a (1 - mi)i, (2) andinactivity fortheyear, wherea andi are thetotalnumberofhoursofactivity Thisis closelyapproximated by respectively. S = exp(-ama - im ) (3) risksless than0.01 perhour;typicalvaluesare less than forper-hour mortality data). Because 0.002 (see below; S. C. Adolphand B. S. Wilson,unpublished = in can as a + i number of hours this a year), expression be rewritten 8,766(the S = exp[a(mi - ma) - 8,766mi]. (4) (e.g., becauseof In thespecialcase in whichall mortality occursduringactivity avianpredation), S = exp(-ama). (5) withdifferent risks activityseasonsbutthesamehourlymortality Populations seasons willdiffer inexpectedannualsurvivalrates.In particular, longeractivity willresultin lowerS ifma > mi; theempiricalstudiesdiscussedabove suggest thatthismayoftenbe true.The degreeofvariationin S dependson thevalues twofold overa typical ofmaandmi(fig.3). For example,S variesapproximately rangeofactivityseasonsif ma = 0.0005and mi = 0.0. However,S variesrelaover the same rangeif ma = 0.0001and mi = 0.0. Similarly, tivelyslightly This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES b a 0 0 03 --~~~~~~~ - 00 ir .1~~~0 - UJ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ z 281 -zM HOURS OF ACTIVITYPER DAY, h ENERGY ASSIMILATED PER DAY, Ea FIG. 4.-Model assumptionsfordaily energyassimilationand allocationtowardreproduction by individuallizards. a, Daily energyassimilationEa (in arbitraryunitsof energy)as a functionof activitytimeh. Dashed line illustratesthe special case where c2 = 0. b, Amount of energyallocated per day to reproduction,Er, as a functionof Ea. Above a daily energy thresholdEt (daily maintenancerequirements),a constantfractionfofeach day's assimilated energyis allocated to reproduction. of deathsoccur variationin S is reducedas mi increases;as a greaterfraction in variation season will have a smallereffect.Figure3 duringinactivity, activity in survivalrate(i.e., greaterthantwofold) thatlargedifferences also illustrates amonglizardpopulationsor betweenyearsin a singlepopulationare likelyto in mortality differences risksin additionto differences in activity. reflect Thisis the between S and to due a; doublinga reducesS by exponentialrelationship less thana factoroftwo. Ourmodelforsurvivalrateassumesthatvaluesformaandmiare independent ofactivity wouldbe violatedby patterns (thevaluesofa and i). Thisassumption that are either to animals activetoo infrequently obtainenoughfoodor are so activethattheycannotmaintaina positiveenergybalance(Marlerand Moore to estimatea priori;however,they 1988,1989).Valuesformaandmiare difficult can be estimated fromsurvivalratedata.In ourtestofthemodel(see below)we givean example.We knowof no otherpublishedestimatesforhourlymortality risksin reptiles. EnergyAssimilationand Allocation to Reproduction We model energyintake and allocation to reproductionon a daily basis. An individual'sdaily energyassimilation(Ea) may be limitedby eitherpreycapture rate or by digestionand absorptionrates(Congdon1989). In eithercase, Ea shouldvarypositivelywithhoursof activity:morepreycan be captured,and will be fasterwhena lizardspendsmoretimeat a digestionand assimilation higherTb.We assumethatEa increaseswithdailyactivitytimeh accordingto therelationship Ea= clh-C2h2, (6) unitsof energy(fig.4a) and cl and c2 are whereEa is expressedin arbitrary as h variesfrom0 to 12 h constantschosenso thatEa increasesmonotonically This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE AMERICAN NATURALIST 282 and is maximizedat h = 12 h. Thatis, energyassimilatedper hourdecreases Theformofthisrelationtime(diminishing withincreasing dailyactivity returns). due to gut size, foodpassage rate, limitations shipcould reflectphysiological satiation,and the like. Variationin preycaptureprobability (amongdifferent reform.Finally,diminishing timesof day) wouldlikewiseyieldthisfunctional turnscouldresultfrombehavior,iflizardsdo notuse all ofthepotential activity timeavailableto them(Sinervoand Adolph1989;Sinervo1990;see also Simon and Middendorf 1976;Rose 1981). is supported forEa (diminishing Thisgeneralrelationship returns) bythelaboraabove (Avery1984;Sinervoand torystudieson lizardgrowthratesmentioned Adolph1989;Sinervo1990).Dependingon thepopulationand species,growth to c2 = 0) to curvilinear linear(corresponding curvesvariedfromapproximately withpeaks near 12 h (C2 = 0.04 cl). This suggeststhatenergyintakein these form. juvenilelizardshad a similarfunctional each day duringthe We assumethatfemalesallocateenergyto reproduction reproductive season, iftheirintakeexceeds a minimum dailyenergythreshold Abovethisthreshold, maintenance allocationto requirements). Et (representing ofenergyassimilated. reproduction (Er) is assumedto be a linearfunction Thus, , E = t?for r f(E -Et), Ea<Et forE >2Et, (7) wheref is a fractionless thanone (fig.4b). The difference Ea - Er includes and growth.For simplicity metaboliccostssuchas locomotion we assumef and oftimeofyear. Et to be independent We assumethatlizardsallocateenergyto reproduction throughout thereproductiveseason,whoselengthis 2y - n d, where2yis thelengthoftheactivity season(as above) and n is thelengthin daysofthenonreproductive season.The minimum valueofn is set by theamountoftimenecessaryforeggsto hatch(in to acquiresufficient oviparousspecies) and forhatchlings energyreservesfor We also assumethatn does not varyamongdifferent overwintering. environments.In reality,n couldbe shorterin warmenvironments becauseeggswould lizardsin warmenvironments incubatein less time;alternatively, mightcurtail in longern. reproduction earlier,resulting Totalannualenergyassimilatedis then = Eannual (8) Ea aij where Ea 2cd 1 -7ly2 - 4C2d2(1 _ j2/y2). (9) Thisyields Eannual = dy[c Tr - (16dC2/3)], (10) whichshows thatthe annualenergybudgetincreaseswiththe lengthsof the season2yand themaximum activity activity day 2d. This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES 283 annualreproductive Similarly, investment is givenby = Rannual f_y rY Erai = f V- 1 -itf(Ea - () Et)ai, where It= - I c- 4C2Et (16d2C2) (12) limit(y - n) is thefinalday andEa[h(j)] is givenabove; theupperintegration limit-ji is necessaryto of thereproductive season, and thelowerintegration avoid havingnegativevalues forEr earlyin the activityseason whenEa < Et season (-jt is thevalueofj forwhichEa = Et). We assumethatthereproductive endsbeforeEa againfallsbelowEt (i.e., that[y - n] < jt). The solutionto this is integral = fc, d/yx {(y Rannual - n) Vy2 - (y - n)2 +jt y2 _ + y2sin-1[(y- n)/y]+ y2sin-l(it/y)} - 4fd2c2/3y2[2y3 + 3y2jt - 3yn2 + n3 - j3] - fEt(Y (13) - n + it) Because thisexpressioninvolvesmanyterms,the effectsof activityseason and energeticparametersare not immediately apparent.In the simplestcase (setting c2, n, and Et equal to zero) thissolutionreducestofdyclr, showingthe on the area of the activityellipseand the energy lineardependenceof Rannual We assumethatRannual intakeandallocationparameters. is proportional to annual thisincludestheassumption thattheenergetic costperoffspring fecundity; does notvaryamongenvironments. We exploredthegeneralsolution(eq. [13]) by evaluating fordifferent Rannual valuesanddifferent parameter activity ellipsesizes. We choseseasons(2y)rangand maximum ingfrom120to 300 d (30-dincrements) day lengths(2d) ranging from8 to 12 h (1-hincrements), thevarietyof thermalenvironapproximating lizardsat different mentsencountered bytemperate-zone latitudesandaltitudes. 5a. Note thattherelationship An exampleis shownin figure betweenRannual and linearovera widerangeof ellipsearea (= annualactivity time)is approximately termsin theintegral solutionabove. Also activityseasonsdespitethenonlinear involvessome variationin Rannual fora givenellipse notethattherelationship area. This is because of thecurvilinear betweenenergyintakeand relationship time(fig.4a). For activityellipseswiththesamearea, an ellipsewitha activity highervalueofy (longerseason)buta lowervalueofd (shorter days)willresult in a largerannualenergybudgetand a largerallocationto reproduction. While values (forf, Et, and n) affectthequantitative different parameter relationship and annualactivity betweenRannual does notchange. time,thequalitative pattern In general,a twofoldincreasein annualactivity timeincreasesRannual bya factor of 1.4-3.5. Underourmodelbothpredictedannualsurvivalrate(fig.3) and annualreproductiveinvestment (fig.5a) varywiththe lengthof the activityseason. This suggeststhatlizardlifehistoriescould differsubstantially amongpopulations This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE AMERICAN NATURALIST 284 a b 1.0- 1.0 0:8 | 0.8 0~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ E 0.6- Eo ~ C: 500 . 0.6- 1*. ~ ~ 0 0400 0.2 0.0 0 0.6-~~~00. 0.6- E ** 0.0 0.2 1000 1500 2000 2500 Annual ActivityTime (hours) 3000 0.0 0.3 0. 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 Annual Adult Survivorship FIG. 5.-Model predictionsof annual reproductiveallocation(Rannual) evaluatedforactivity seasons rangingfrom=750 to =3,000 h yr-'. Values ofRannual are normalizedto themaximum as a functionof activityseason length.In thisexample, value of 404.6 energyunits.a, Rannual cl = 1.0, c2 = 0.042, f = 0.3, n = 60, and Et = 0.0. Otherparametervalues yield similar graphsthatdiffermainlyin overall slope. Connected points representactivityseasons with the same numberof days (2y) but different maximumday lengths(2d); nonlinearitiesresult fromthediminishing-returns assumptionforenergyassimilation(fig.4b). b, Predictedpattern and annual adult survivalrateamongpopulationsfromdifferent ofcovariationbetweenRannual thermalenvironments,combiningreproductiveoutputfromfig.5a and survivalrate curves fromfig. 3b (with ma = 0.0003 and mi = 0.00003). This negative relationshipbetween survival rate and reproductiveoutput is a proximateconsequence of variationin activity season length.Similarly,data presentedby Tinkle (1969) show a negativerelationship(r = -0.88, P < .001) between annual adult survivalrate and annual fecundityon the basis of empiricalstudies of 14 lizard populations(13 species). These data matchpredictionsof both our mechanisticmodel and evolutionarymodels. ofdifferent simplybecauseoftheproximate effects thermal environments, without any geneticdifferences. This possibility has been givenless attention than evolutionary explanations (Tinkleand Ballinger1972;Stearns1977,1980,1984; Ballinger1983;Joneset al. 1987;Dunhamet al. 1988;Jamesand Shine 1988), almostnothing is knownaboutthegeneticbasis of lizardlifehistories although (Ballinger1983;Sinervoand Adolph1989;Fergusonand Talent1993). Evolutionary life-history theorypredictsthathighannualreproductive investmentwill evolve whenannualadultsurvivalrateis low (Tinkle1969;Stearns 1977;Pianka 1988). Underthistheory,comparisonsof speciesor populations betweensurvivalrateand fecundity shouldshowa negativecorrelation (Tinkle based model offersthe same prediction, 1969). Our physiologically without betweenpopulations evolveddifferences (fig.5b). Thus,thenegativecorrelation betweenannualfecundity and annualsurvivalrateobservedby Tinkle(1969) couldreflecttheproximate influence of temperature ratherthan(or in addition to) adaptiveevolutionof reproductive investment to compensateformortality. Ourmodelsuggeststhatthermal effects on reproductive outputwillautomatically compensate(at least partially)forthermaleffectson survivalrate,if foodresourcesare not limiting. Because bothevolutionary and physiological models This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES 285 predictthe same phenotypic patterns,simplecomparisons of wildpopulations willnotdistinguish betweenthem. TESTING THE MODEL: DATA FROM SCELOPORUS UNDULATUS and annualadultsurvivalratewill Our modelpredictsthatannualfecundity We testedthesepredictions co-varywithannualhoursofactivity. usingpublished datafrom11populations oftheeasternfencelizard(Sceloporusundulife-history in montane, latus).This species is widespreadin the UnitedStates,occurring woodland,prairie,and deserthabitats(Smith1946).These data werecollected by severaldifferent researchers and weresummarized in Dunhamet al. (1988). EstimatingActivitySeasons We calculatedpotentialactivityseasonsforeach populationusingcomputer and animalTbon thebasis of heattransfer modelsthatestimatemicroclimates principles (Porteret al. 1973;Porterand Tracy1983).For each population, we andmaximum obtainedclimatedata(monthly airtemperatures) averageminimum fromthenearestavailablelocationforeach yearofthefieldstudy(U.S. Weather wereadjustedfordifferences in altitudebetweenstudy Bureau).Temperatures sitesand climatestationsat the theoretical adiabaticcoolingrateof 9.9?C per kilometer ofaltitude(Sutton1977).Detaileddiscussionofthismodelis presented in Porteret al. (1973).Solarradiation was calculatedon thebasis ofMcCullough andPorter(1971;software SOLRAD [developedbyW. P. Porter]availprogram ablethrough WISCWARE,University ofWisconsinAcademicComputer Center, alti1210WestDaytonStreet,Madison,Wis. 53706).Exceptfortemperatures, tudes,andlatitudes, we assumedall studysiteswereequivalentintheirmeteorologicalcharacteristics (e.g., windspeed,cloudcover,soil thermal conductivity) becauselocallyspecificinformation was unavailable.Table 1 liststhevaluesof we used in thesesimulations. parameters and simulations estimatedair and soil temperature The microclimate profiles forthefifteenth at ?1-h intervals radiation conditions dayofeach month.These modelthatcalculatedtheequilibrium datawerethenused as inputto a computer and Lizardmorphological Tbattainable bya lizardwithgiventhermal properties. 1. We assumed in table used in thisanalysisare given thermalcharacteristics a typicaladultbody size forS. undulatus(Dunhamet al. 1988)and obtained forabsorptivity measurements and Gates (Norris1967)and emissivity (Bartlett assumed that lizards We could be of radiation. active whenever 1967) potentially in them to reach a their microclimates permitted Tb preferred bodytemperature rangeof32?-37?C(Bogert1949;Avery1982;Crowley1985).Themodelcalculated at <5-minintervalsthroughout Tbestimatesforvariouspossiblemicrohabitats fromfullsunlight theday. Lizardswere"allowed" to chooseperchesranging to fullshadeand at anyheightfromthegroundto 2.0 m offtheground.Sceloporus use (Smith1946),and Sceloporus undulatusare flexiblein theirmicrohabitat andperchheight lizardsareknowntouse baskingfrequency choiceas thermoregulatorymechanisms (Adolph1990a). The computerprogramdetermined how muchtimelizardscould have been This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 286 THE AMERICAN NATURALIST TABLE 1 PARAMETER ANDANIMALENERGETICS VALUESUSED IN MICROCLIMATE MODELS Value Parameter Environment: Soil solar absorptance Soil density x specificheat Soil thermalconductivity Substrateroughnessheight Cloud cover Wind speed at heightof 2.0 m Humidity Slope Lizard: Body mass Snout-ventlength Solar absorptivity Infraredemissivity Surface area, silhouetteareas, and shape factors PreferredTb range .70 2.096 x 106m-3 K-l 2.5 W m-1 K-' .001 rn None (clear skies) Varies daily from.5 to 2.5 m s Varies daily from20% to 50% 100 north-facing 10 g 65 mm .95 1.0 See Porterand Tracy (1983) 320-370C NOTE.-Models and parametersare describedin detail in Porteret al. (1973) and Porterand Tracy (1983). Values were assumed to be equal forall studysites. activeduringan averageday of each month,multiplied thisby thenumberof daysin thatmonth,and summedthesevaluesfortheyear.For empirical studies lastingmorethan 1 yr,we used climatedata foreach year of the studyand estimatesofannualactivity time.Calculatedpotential averagedtheresulting annualactivityseasons rangedfrom1,707h foran Ohio population to 3,012h for in Texas. a population Survival Rate Populationswithlongerpotentialactivityseasonshad lowerobservedannual survival rateofadultfemales(fig.6a). Thissuggests thatmortality riskwas higher foractivethanforinactivefencelizards.The relationship betweensurvivalrate and activity timeallowsus to estimatetheserisks.Fromequation(4), ln(S) = (mi - ma)a - 8,766mi. (14) Withthisequationand theassumptionof equal risksforall populations, leastof thedata in figure 6a yieldsestimates of0.0 to 5.8 x 10-5 squaresregression per hourformi (95% confidenceintervalforthe intercept, omitting negative values formi). The slope of the regression [undefined] (whichestimatesmi ma) is -1.97 x 10' (confidence interval,+8.3 x 10-), suggesting thatma is x 2.0 10' perhour.However,thisestimateofmais impossibly approximately high;even ifall mortality occurredduringactivity, themaximum value forma wouldbe lower,as follows.We obtainedmaximum estimates formabyassuming mi = 0 and usingequation(5) separatelyforeach population.Estimatedmaximumma averaged 5.5 x 10-i perhourandrangedfrom3.0 x 10-4 to 9.3 x 10-4. The discrepancy betweentheregression estimateformaandtheindividual This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 287 TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES a 0.6 1 0.40 1500 b >- 40 20 500 0.2- ,U. S 0.~1 z . 0.05 1500 0 2000 c 01% ~ 3000 2500 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ CD,1 z z .4 0 1500 2000 2500 3000 d ~~~2.10 2.0 42 1500 UJ ~~~-1.0. * 2000 2500 3000 ANNUALACTIVITYTIME (HOURS) 0 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~-2.0 1500 2000 2500 3000 ANNUALACTIVITYTIME (HOURS) features(publisheddata fromfieldstudies, FIG. 6.-Relationshipsbetweenlife-history microcliinDunhametal. 1988)andlength ofactivity season(calculated through summarized forNorthAmerican oftheiguanidlizardSceloporusundulamatesimulations) populations seasonand annualsurvivalrateof tus.a, Negativerelationship betweenlengthofactivity adultfemales,plottedon a logarithmic scale (see eq. [4]) (r = -0.76 fornatural-logbetweenannualfecundity transformed (mean data,N = 10,P < .01).b, Positiverelationship season ofactivity ofeggsperclutchx meannumber ofclutchesperyear)andlength number (r = 0.55, N = 11, P < .05). c, Positive relationshipbetweentotal annual egg mass (annual x meanmassperegg)andlengthofactivity season(r = 0.36,N = 10,P > .1). fecundity seasonandresidualtotalannualeggmass, betweenlengthofactivity d, Positiverelationship femalesineachpopulation ofmature aftercorrecting forbodysize (meansnout-vent length) (r = 0.82, N = 10, P < .005). Lines show least-squaresregressions;P values forcorrelation based on ourmodel. testsof a priorihypotheses one-tailedsignificance coefficients reflect estimatesindicatesthatthereducedsurvivalrateofS. undulatus poppopulation risk an increasein hourlymortality ulationswithlongeractivityseasonsreflects times.Thisconclusion oflongeractivity (eitherma or mi)inadditionto theeffect is higherat low is consistentwiththe commonbeliefthatpredationintensity latitudesand at low altitudes(butsee Wilson1991).In eithercase, ouranalysis riskaveragedat least 10 timeshigherforactive indicatesthathourlymortality fencelizardsthanforinactivelizards. This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 288 THE AMERICAN NATURALIST Annual ReproductiveOutput Dunhamet al. (1988) estimatedannualfecundity foreach populationof S. meannumberofclutches undulatusas themeanclutchsize timestheestimated laidperyear.Theyalso provideinformation on averageeggmass.We usedthese data to comparetwo measuresof annualreproductive output,annualfecundity andtotalannualeggmass,totheestimated lengthofactivity seasons.Bothannual fecundity (fig.6b) and totalannualegg mass (fig.6c) werepositively correlated seasonlength, as predicted withactivity byourmodel.However,therelationship fortotalannualeggmasswas notstatistically andinbothrelationships significant, for.Although muchof thevariationwas unaccounted ourmodelpredictssome scatterintheserelationships (fig.5a), additional factorsarelikelyto be involved. and bodysize are potential Food availability complicating factors,as bothare knownto influence reproductive outputin lizards(Ballinger1977,1983;Stearns 1984;Dunhamand Miles 1985;Dunhamet al. 1988;MilesandDunham1992).To whether inbodysize ofS. undulatus variation determine intraspecific was related to variation in reproductive a regression outputwe performed oftotalannualegg massagainstthemeansnout-vent length(SVL) ofadultfemalesin each population(Dunhamet al. 1988).We founda strongpositiverelationship (totalannual egg mass [g] = - 10.51 + 0.26 SVL [mm]; r = 0.76, N = 10, P < .05). Thus, variation in SVL amongpopulationsaccountedfor58% ofthevariation in total annualeggmass. We used residualsfromthisregression as size-corrected measuresof annualegg mass production. Residualtotalannualegg mass was posiwithlengthofactivityseason(fig.6d). Together, tivelycorrelated bodysize and lengthofactivityseasonaccountedfor87% ofthevariationin annualeggmass. Thisleavesrelatively littleresidualvariation tobe explainedbyamong-population in factorssuchas reproductive variation investment or foodavailability. and size season to influence annualreproduction in Bothactivity body appear size can be into model our the S. undulatus.Body incorporated general through of metabolism, energyintakeand allocationfunctions (fig.4); the allometries forlizards allocationare well characterized energyintake,and reproductive Bennett Bennett and Dawson Dunham et al. (Fitch1970; 1976; 1982;Nagy1983; food could alter the of the intake curves 1988).Similarly, availability shape energy (fig.4a) and perhapstheformof the allocationfunction (fig.4b). Overalllifediffered wouldthendependon howfoodavailability history patterns amongtherand Dunham showed thattheexGrant For malenvironments. example, (1990) traitsin Sceloporus merriamidepends on the interaction pression of life-history constraints. betweenresourcelevelsand thermal relatedto seasonality.For example, Body size is also likelyto be intimately lizardsbornin a longactivityseasonmaybe able to growsufficiently hatchling so thatthey reach minimumreproductivesize in time to reproducein the next year. These lizards would be relativelysmall at maturityand consequentlywould have small clutch sizes. In contrast,lizards born in a shorteractivityseason mightnot reach reproductivematurityuntiltheirsecond year, when theywould be large, and would consequentlyhave large clutches. This potentialnegative effectof activityseason lengthon clutch size would counterthe positive effect This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES 289 betweenactivityseason of season lengthon clutchfrequency.The interplay on the maybe an important influence length,body size, and clutchfrequency evolutionofeggsize and clutchsize in lizards. DISCUSSION low Evolutionary life-history theorypredictsthatpopulationsexperiencing and highfecundity, adultsurvivalrateswillevolveearlymaturity comparedto considerations suggest populations withhighadultsurvivalrates.Physiological can resultfroma whollydifferent oflife-history thatthesamepattern phenotypes inducedvariationdue to theeffects oftemperature mechanism: environmentally fortheinterpretation Thisresulthas implications on activity timeand energetics. andforthephenotypic forlife-history response oflife-history evolution, patterns, to climatechange. ofpopulations theneedformoreinformation on thegeneticbasis ofintraFirst,it highlights in lizardlifehistories.Comparisons variation oflifehistories as andinterspecific are imperfect testsofevolutionary theorybecause measuredin wildpopulations whether determining nonevolutionary processesmaybe involved.In principle, are genetically based is straightforward, via common-garden life-history patterns eitherin the fieldor in the laboratory (Ballinger1979;Bervenet experiments studiesare rarely al. 1979;Bervenand Gill 1983).In practice,common-garden butalso forphysiowithreptiles;thisis truenotonlyforlifehistories performed logical and behavioral traits(Adolph 1990b; Garland and Adolph 1991). Several studiesofgrowth and life-history traitsinSceloporushavebeen common-garden and Adolph1989;Sinervo experiments: Sinervo completedrecently(laboratory data; 1990;FergusonandTalent1993;B. Sinervoand S. C. Adolph,unpublished P. H. Niewiarowski fieldtransplant and W. M. Roosenberg,perexperiments: sonalcommunication). Each of thesestudiesfoundevidenceof interpopulation as well as evidenceof strong differences thatmayreflectgeneticdifferences, environmental effects.These findings variationamong indicatethatphenotypic naturalpopulations is likelyto havebothenvironmental andgeneticcomponents. is thatlife-history can One consequenceofphenotypic plasticity optimization if the reaction be achievedwithoutgeneticdifferentiation amongpopulations, traitsare appropriately normsoflife-history shaped.However,decidingwhether reactionnormis problematic. The trounaturalselectionhas shapeda particular must norm have some if is that reaction because of ble shape(even flat) every nature of For most thefundamental organisms (Stearns1989). physicochemical we do notknowenoughabouttheunderlying todetermine physiology organisms, in the a would be absence of selective that what agent. presumed exactly shape truein thecase oftemperature, whichcauses a widevariety Thisis particularly and life-history offunctional traits;thepreciseform responsesin physiological is rarelypredictable fromlowerlevelsofintegration ofa responseto temperature null model (e.g., enzymekinetics).Consequently,we have no physiological be gaugedfora singlepopulation. ofadaptation might againstwhicha hypothesis based differences in reactionnormsamongpopulationsin Findinggenetically different environmentsoffersmuch betterevidence foradaptive evolution(Ber- This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 290 THE AMERICAN NATURALIST venet al. 1979;Conoverand Present1990;B. Sinervoand S. C. Adolph,unpublisheddata). Our modelpredictsthatthe proximateeffectsof temperature on lizardlifetraitswillbe at leastpartially withlowsurvival history compensatory: populations rates will also have highfecundity.In addition,these populations are likelyto reachreproductive maturity earlier,althoughour modeldoes not includethis trait.Thissuggeststhattheimpactofdirectional climatechangeon lizardpopulaas longas factorssuchas foodavailtiondynamicswillbe partially ameliorated, riskare notalteredsubstantially. abilityand mortality However,thesefactors dependon thephysiological responsesofotherspecies,bothpreyandpredators. For example,food availability mightbe largelydetermined by the overlapbetweenlizardand preyactivitytimes(Porteret al. 1973).If theseactivitytimes to a givenchangeinthethermal responddifferently environment, expecteddaily ratesmaychange,whichwouldchangetherelationship encounter betweenentime(fig.4a). Similarly, lizardmortality ergyintakeandactivity ratesmaydepend on overlapbetweenactivitytimesof lizardsand theirpredators.Thus,thereto climatechangeis likelyto dependon thephysiolsponseoflizardpopulations ogyofotherspeciesas wellas theirownphysiology. is an important linkbetweenthethermal Activity environment and lizardlife histories.Therefore, are a likelytargetofnaturalselection.Inactivitypatterns deed, Fox (1978)foundthatsurvivalratesof individualUta stansburiana were withtheirtemporal andspatialactivity correlated In manycases,lizards patterns. mayuse less thanthemaximum potentialactivitytimeafforded by thethermal environment (Simonand Middendorf 1976;Sinervoand Adolph1989;Sinervo 1990),whichsuggestsa compromise betweenthebenefits and costs of activity (Rose 1981).The difference betweenpotential andrealizedactivity timesinvolves behavioraldecisionsby thelizardthatmaybe shapedin partby local selective regimes.The functional relationships betweenactivityand life-history traitsare likelyto playa keyrole in theevolutionof activitypatterns.Grantand Porter (1992)presenta preliminary analysisof a behavioraloptimization modelformulatedin theseterms. inlife-history traitscomplicates Phenotypic plasticity theformulation ofevoluofpatterns observedin nature.Idetionarymodelsas well as theinterpretation theoriesshouldincorporate bothproximateand evolutionary ally,life-history responses(Ballinger1983;Siblyand Calow 1986;Stearnsand Koella 1986;Beuchatand Ellner1987).The modelpresentedhereoffers a generalframework for lizardlifehistoriesfroma physiological Futureefforts modeling standpoint. can be tailoredto particularspecies or environments detailedmechanistic through modelsofprocessessuchas digestionand metabolism (e.g., Beuchatand Ellner on resourceabundance(Joneset 1987;Grantand Porter1992)and information al. 1987). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thankD. Bauwens, T. Garland, Jr.,J. Jaeger,R. M. Lee III, G. Mayer, P. S. Reynolds,B. Sinervo, B. Wilson,and two anonymousreviewersforhelpful This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES 291 discussion or commentson the manuscript.This researchwas supportedby the Officeof Health and EnvironmentalResearch, U.S. Departmentof Energy, throughcontractDE-FG02-88ER60633 to W.P.P., and by a Guyer Fellowship (Departmentof Zoology, Universityof Wisconsin) to S.C.A. LITERATURE CITED Abts, M. L. 1987. Environmentand variationin life historytraitsof the chuckwalla, Sasiiomalius obesus. Ecological Monographs57:215-232. on microhabitatuse by two Sceloporuls Adolph,S. C. 1990a. Influenceof behavioralthermoregulation lizards. Ecology 71:315-327. 1990b. Perch heightselection by juvenile Sceloporus lizards: interspecificdifferencesand relationshipto habitatuse. Journalof Herpetology24:69-75. Anderson,R. A., and W. H. Karasov. 1988. Energeticsof the lizard Cnemidophorustigrisand life historyconsequences of food-acquisitionmode. Ecological Monographs58:79-110. Avery,R. A. 1971. Estimatesof food consumptionby the lizardLaceita viviparaJacquin.Journalof Animal Ecology 40:351-365. 1973. Morphometricand functionalstudies on the stomach of the lizard Lacerta vivipara. Journalof Zoology (London) 169:157-167. and food consumptionin two sympatriclizard 1978. Activitypatterns,thermoregulation species (Podarcis muralis and P. sicula) fromcentral Italy. Journalof Animal Ecology 47:143-158. UniversityPark Press, Baltimore. 1979. Lizards: a studyin thermoregulation. Pages 93-166 in C. Gans and 1982. Field studies of body temperaturesand thermoregulation. F. H. Pough, eds. Biology of the Reptilia. Vol. 12. PhysiologyC: physiologicalecology. Academic Press, New York. Symposia of the 1984. Physiologicalaspects of lizard growth:the role of thermoregulation. Zoological Society of London 52:407-424. in lizard Avery, R. A., J. D. Bedford, and C. P. Newcombe. 1982. The role of thermoregulation in a temperatediurnalbasker. BehavioralEcology and Sociobibiology:predatoryefficiency ology 11:261-267. Ballinger,R. E. 1977. Reproductivestrategies:food availabilityas a source of proximalvariationin a lizard. Ecology 58:628-635. 1979. Intraspecificvariationin demographyand lifehistoryof the lizard, Sceloportusjarrovi, along an altitudinalgradientin southeasternArizona. Ecology 60:901-909. variations.Pages 241-260 in R. B. Huey, E. R. Pianka, and T. W. Schoener, 1983.Life-history eds. Lizard ecology: studies of a model organism.Harvard UniversityPress, Cambridge, Mass. Bartlett,P. N., and D. M. Gates. 1967. The energy budget of a lizard on a tree trunk.Ecology 48:315-322. Bennett,A. F. 1980. The thermaldependence of lizard behaviour. Animal Behaviour 28:752-762. 1982. The energeticsof reptilianactivity.Pages 155-199 in C. Gans and F. H. Pough, eds. Biology of the Reptilia. Vol. 13. PhysiologyD: physiologicalecology. Academic Press, New York. Bennett,A. F., and W. R. Dawson. 1976. Metabolism.Pages 127-223 in C. Gans and W. R. Dawson, eds. Biology of the Reptilia. Vol. 5. PhysiologyA. Academic Press, New York. traits.American geographicvariationin life-history Berven, K. A., and D. E. Gill. 1983. Interpreting Zoologist 23:85-97. Berven, K. A., D. E. Gill, and S. J. Smith-Gill.1979. Countergradientselection in the green frog, Rana clamitans. Evolution 33:609-623. Beuchat, C. A. 1989. Patternsand frequencyof activityin a highaltitudepopulationof the iguanid lizard, Sceloporus jarrovi. Journalof Herpetology23:152-158. by a Beuchat, C. A., and S. Ellner. 1987. A quantitativetest of lifehistorytheory:thermoregulation viviparouslizard. Ecological Monographs57:45-60. This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 292 THE AMERICAN NATURALIST Bogert, C. M. 1949. Thermoregulationand eccritic body temperaturesin Mexican lizards of the genus Sceloporus. Anales del Institutode Biologia de la UniversidadNacional Autonomade Mexico 20:415-426. Bradshaw, S. D. 1986. Ecophysiologyof desert reptiles.Academic Press, New York. Buffenstein,R., and G. Louw. 1982. Temperatureeffectson bioenergeticsof growth,assimilation efficiencyand thyroidactivity in juvenile varanid lizards. Journal of Thermal Biology 7:197-200. Bull, J. J. 1980. Sex determinationin reptiles.QuarterlyReview of Biology 55:3-21. Christian,K. A., and C. R. Tracy. 1981. The effectof the thermalenvironmenton the abilityof hatchlingGalapagos land iguanas to avoid predationduringdispersal. Oecologia (Berlin) 49:218-223. Christian,K. A., C. R. Tracy, and W. P. Porter. 1983. Seasonal shiftsin body temperatureand use of microhabitatsby Galapagos land iguanas (Conolophus pallidus). Ecology 64:463-468. Clausen, J., D. D. Keck, and W. M. Hiesey. 1940. Experimentalstudieson the natureof species. I. The effectof varied environmentson westernNorthAmericanplants. Carnegie Instituteof WashingtonPublicationno. 520. Carnegie Instituteof Washington,Washington,D.C. Congdon,J. D. 1989. Proximateand evolutionaryconstraintson energyrelationsof reptiles.Physiological Zoology 62:356-373. Congdon,J. D., A. E. Dunham, and D. W. Tinkle. 1982. Energybudgetsand lifehistoriesof reptiles. Pages 233-271 in C. Gans and F. H. Pough, eds. Biology of the Reptilia.Vol. 13. Physiology D: physiologicalecology. Academic Press, New York. variationin growthrate: compensation Conover, D. O., and T. M. C. Present. 1990. Countergradient for lengthof the growingseason among Atlanticsilversidesfromdifferent latitudes.Oecologia (Berlin) 83:316-324. Cowles, R. B., and C. M. Bogert. 1944. A preliminarystudyof the thermalrequirementsof desert reptiles.Bulletinof the AmericanMuseum of Natural History83:261-296. in thelizardSceloporus undulatus:support Crowley,S. R. 1985. Thermalsensitivityof sprint-running fora conservativeview of thermalphysiology.Oecologia (Berlin) 66:219-225. Davis, J. 1967. Growth and size of the western fence lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis). Copeia 1967:721-731. Dawson, W. R. 1967. Interspecificvariation in physiologicalresponses of lizards to temperature. Pages 230-257 in W. W. Milstead, ed. Lizard ecology: a symposium.Universityof Missouri Press, Columbia. Derickson, W. K. 1976. Lipid storageand utilizationin reptiles.AmericanZoologist 16:711-723. individualgrowthrates in Dunham, A. E. 1978. Food availabilityas a proximatefactorinfluencing the iguanidlizard Sceloporus merriami.Ecology 59:770-778. Dunham, A. E., and D. B. Miles. 1985. Patternsof covariationin life historytraitsof squamate reptiles:the effectsof size and phylogenyreconsidered.AmericanNaturalist126:231-257. Dunham, A. E., D. B. Miles, and D. N. Reznick. 1988. Life historypatternsin squamate reptiles. Pages 441-522 in C. Gans and R. B. Huey, eds. Biology of the Reptilia. Vol. 16. Ecology B: defense and lifehistory.Liss, New York. Dunham,A. E., B. W. Grant,and K. L. Overall. 1989. Interfacesbetweenbiophysicaland physiological ecology and the population ecology of terrestrialvertebrateectotherms.Physiological Zoology 62:335-355. Duvall, D., L. J. Guillette,Jr.,and R. E. Jones. 1982. Environmentalcontrolof reptilianreproductive cycles. Pages 201-231 in C. Gans and F. H. Pough, eds. Biology of the Reptilia. Vol. 13. PhysiologyD: physiologicalecology. Academic Press, New York. Ferguson,G. W., and T. Brockman. 1980. Geographicdifferences ofgrowthrateofSceloporus lizards (Sauria: Iguanidae). Copeia 1980:259-264. Ferguson,G. W., and L. G. Talent. 1993. Life-historytraitsof the lizard Sceloporus undulatusfrom two populationsraised in a common laboratoryenvironment.Oecologia (Berlin) 93:88-94. Ferguson, G. W., C. H. Bohlen, and H. P. Woolley. 1980. Sceloporus undulatus: comparativelife historyand regulationof a Kansas population.Ecology 61:312-322. Fitch, H. S. 1970. Reproductive cycles in lizards and snakes. Universityof Kansas Museum of Natural HistoryMiscellaneous Publication52. This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES 293 ofthelizardUta stansburiana. Ecology phenotypes Fox, S. F. 1978.Naturalselectionon behavioral 59:834-847. of vertebrate differentiation populations. Garland,T., Jr.,and S. C. Adolph.1991.Physiological 22:193-228. AnnualReviewofEcologyand Systematics of thelizardSceloporus in mountain and lowlandpopulations Goldberg,S. R. 1974.Reproduction occidentalis. Copeia 1974:176-182. timeand physiological in activity forthermoregulating performance Grant,B. W. 1990.Trade-offs Ecology71:2323-2333. desertlizards,Sceloporusmerriami. on theactivity of the imposedtimeconstraints Grant,B. W., and A. E. Dunham.1988.Thermally desertlizardSceloporusmerriami. Ecology69:167-176. of thedesert constraints and lifehistories 1990.Elevationalcovariation in environmental lizard Sceloporus merriami.Ecology 71:1765-1776. constraints onectotherm energy globalmacroclimatic Grant,B. W., andW. P. Porter.1992.Modeling budgets.American Zoologist32:154-178. hibernation. P. T. 1982.Reptilian Pages53-154inC. Gansand F. H. Pough,eds. Biology Gregory, D: physiological oftheReptilia.Vol. 13. Physiology ecology.AcademicPress,New York. of threespeciesof on the digestiveefficiency Harwood,R. H. 1979.The effectof temperature lizards, Cnemidophorus tigris,Gerrhonotusmulticarinatus,and Sceloporus occidentalis. 63:417-433. and Physiology A, Comparative Physiology Comparative Biochemistry Heatwole,H., T.-H. Lin, E. Villal6n,A. Muniiz,and A. Matta.1969.Someaspectsofthethermal ofHerpetology 3:65-77. ecologyofPuertoRicananolinelizards.Journal andtheecologyofreptiles. Pages25-91inC. Gansand Huey,R. B. 1982.Temperature, physiology, F. H. Pough,eds. Biologyof theReptilia.Vol. 12. Physiology ecology. C: physiological AcademicPress,New York. thermal andecologyofectotherms: physiology Huey,R. B., andR. D. Stevenson.1979.Integrating a discussionofapproaches.American Zoologist19:357-366. 1977.Seasonalvariation inthermoregulatory behavior Huey,R. B., E. R. Pianka,andJ.A. Hoffman. ofdiurnalKalaharilizards.Ecology58:1066-1075. andbodytemperature rocks: Huey,R. B., C. R. Peterson,S. J.Arnold,and W. P. Porter.1989.Hot rocksandnot-so-hot selectionby gartersnakesand its thermal retreat-site consequences.Ecology70:931-944. of Australian lizards:a comparison between strategies James,C., and R. Shine. 1988.Life-history thetropicsand thetemperate zone. Oecologia(Berlin)75:307-316. lifehistoriesof Holbrookiamaculataand Jones,S. M., and R. E. Ballinger.1987.Comparative in westernNebraska.Ecology68:1828-1838. Sceloporusundulatus and W. P. Porter.1987.Physiological and environmental sourcesof Jones,S. M., R. E. Ballinger, variation in reproduction: Oikos48:325-335. prairielizardsin a foodrichenvironment. differences inenergy andexpenacquisition Karasov,W. H., andR. A. Anderson.1984.Interhabitat diturein a lizard.Ecology65:235-247. American evolutionary implications. Zoologist19:295-304. Kluger,M. J. 1979.Feverinectotherms: ed. Marshall'sphysiology ofreproduction. Licht,P. 1984.Reptiles.Pages 206-282in E. Lamming, AcademicPress,New York. cues forgonadaldevelopment in temperate reptiles:temperature Marion,K. R. 1982.Reproductive on thetesticular effects andphotoperiod HerpetocycleofthelizardSceloporusundulatus. logica38:26-39. costsof aggression revealedby testosterone Marler,C. A., and M. C. Moore. 1988.Evolutionary male lizards.BehavioralEcologyand Sociobiology in free-living 23:21-26. manipulations costsofaggression intestosterone-implanted malemountain 1989.Timeandenergy free-living Zoology62:1334-1350. spinylizards(Sceloporusjarrovi).Physiological variation in ovariancyclesandclutchsize McCoy,C. J.,andG. A. Hoddenbach.1966.Geographic in Cnemidophorus D.C.) 154:1671-1672. tigris(Teiidae).Science(Washington, clearday solarradiationspectraforthe E. C., and W. P. Porter.1971.Computing McCullough, terrestrial Ecology52:1008-1015. ecologicalenvironment. inthelife-history effects analysesofphylogenetic Miles,D. B., andA. E. Dunham.1992.Comparative Naturalist 139:848-869. ofiguanidreptiles.American patterns controlof seasonalreproducand D. Crews. 1984.Environmental Moore,M. C., J. M. Whittier, This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 294 THE AMERICAN NATURALIST lizardCnemnidophorus Zoology57:544uniparens. Physiological tionin a parthenogenetic 549. and ecologyofdesertiguana(Dipsosaurusdo-salis)eggs:temperature Muth,A. 1980.Physiological Ecology61:1335-1343. waterrelations. in a desertlizard,Sauromalusobesus.Copeia Nagy,K. A. 1973.Behavior,diet,and reproduction 1973:93-102. 1983.Ecologicalenergetics. Pages24-54inR. B. Huey,E. R. Pianka,andT. W. Schoener, HarvardUniversity Press,Cambridge, eds. Lizardecology:studiesof a modelorganism. Mass. anditsthermal indesertreptiles relationships. Pages162-229in Norris,K. S. 1967.Coloradaptation ofMissouriPress,Columbia. W. W. Milstead,ed. Lizardecology:a symposium. University eggsandembryos. ecologyofreptilian Packard,G. C., and M. J. Packard.1988.The physiological Pages523-605in C. Gans and R. B. Huey,eds. BiologyoftheReptilia.Vol. 16. Ecology B: defenseandlifehistory. Liss, New York. ofthelizardUtastansburiW. S., andE. R. Pianka.1975.Comparative ecologyofpopulations Parker, ana. Copeia 1975:615-632. 1976.Thermoregulation oflizardsandtoadsat highaltitudes in Pearson,0. P., andD. F. Bradford. Peru.Copeia 1976:155-170. ofthelizardCnemidophorus partsof tigrisin different autecology Pianka,E. R. 1970.Comparative itsgeographic range.Ecology51:703-720. 1988.Evolutionary ecology.4thed. Harper& Row,New York. forcalculating at different W. P. 1989.New animalmodelsandexperiments potential growth Porter, elevations.Physiological Zoology62:286-313. ofmechanistic ecology.II. TheAfrican W. P., andF. C. James.1979.Behavioral implications Porter, rainbowlizard,Agamaagama. Copeia 1979:594-619. W. P., andC. R. Tracy.1983.Biophysical and time-space utilization, analysesofenergetics, Porter, distributional limits.Pages 55-83 in R. B. Huey,E. R. Pianka,and T. W. Schoener,eds. HarvardUniversity Press,Cambridge, Mass. Lizardecology:studiesofa modelorganism. of Porter,W. P., J. W. Mitchell,W. A. Beckman,and C. B. DeWitt.1973.Behavioralimplications mechanistic ecology.Oecologia(Berlin)13:1-54. in Sceloporusvirgatus. Ecology62:706-716. activity Rose, B. 1981.Factorsaffecting approach.Blackecologyofanimals:an evolutionary Sibly,R. M., andP. Calow. 1986.Physiological Oxford. wellScientific, 1976.Resourcepartitioning and byan iguanidlizard:temporal Simon,C. A., andG. A. Middendorf. microhabitat aspects.Ecology57:1317-1320. ofthermal andgrowth ratebetween ofthewestern populations physiology Sinervo,B. 1990.Evolution fencelizard(Sceloporusoccidentalis). Oecologia(Berlin)83:228-237. of growthratein hatchling Sceloporus Sinervo,B., and S. C. Adolph.1989.Thermalsensitivity behavioralandgeneticaspects.Oecologia(Berlin)78:411-419. lizards:environmental, comparedwith"sideanalysisin "physiological" Sinervo,B., and R. W. Doyle. 1990.Life-history in a varying real" time:an examplewithan amphipod(Gammaruslawrencianus) environment.MarineBiology107:129-139. of thedigestivetract.Pages 589-717in C. Gans and K. A. Gans, Skoczylas,R. 1978.Physiology B. AcademicPress,New York. eds. BiologyoftheReptilia.Vol. 8. Physiology Ithaca,N.Y. Smith,H. M. 1946.Handbookoflizards.Comstock, to theconceptsofreproductive cyclesand the Smith,H. M., and W. P. Hall. 1974.Contributions of the scalarisgroupof thelizardgenusSceloporus.GreatBasin Naturalist systematics 34:97-104. ofreptiles.Pages239-247inW. Weiser,ed. I. F. 1973.Criticalminimum temperatures Spellerberg, on ectothermic Effectsoftemperature Berlin. organisms. Springer, traits:a critiqueofthetheoryanda reviewofthe Stearns,S. C. 1977.The evolutionoflifehistory data.AnnualReviewofEcologyand Systematics 8:145-171. evolution.Oikos35:266-281. 1980.A newviewoflifehistory on patterns ofcovariation inthelifehistory ofsize andphylogeny traitsof 1984.The effects Naturalist 123:56-72. lizardsand snakes.American ofphenotypic BioScience39:436-445. 1989.The evolutionary plasticity. significance This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions TEMPERATURE AND LIZARD LIFE HISTORIES 295 traits: in life-history plasticity Stearns,S. C., and J. C. Koella. 1986.The evolutionof phenotypic Evolution40:893-913. ofreactionnormsforage and size at maturity. predictions N.Y. Krieger,Huntington, Sutton,0. G. 1977.Micrometeorology. 117:1-23. Naturalist timeininsects.American ofphysiological Taylor,F. 1981.Ecologyandevolution Miscellaoftheside-blotched lizard,Utastansburiana. Tinkle,D. W. 1967.The lifeanddemography ofMichigan132:1-182. oftheMuseumofZoology,University neousPublications of oflifehistories effort anditsrelationto theevolution 1969.The conceptofreproductive 103:501-516. Naturalist lizards.American in twospeciesofthelizardgenusUta. Copeia on laboratory survivorship 1970.Comments 1970:381-383. 28:351-359. Herpetologica ofSceloporusundulatus. ofa Utahpopulation 1972.Thedynamics comparaa studyoftheintraspecific Tinkle,D. W., andR. E. Ballinger.1972.Sceloporusundulatus: ofa lizard.Ecology53:570-584. tivedemography lifehistoriesof two syntopicsceloporine Tinkle,D. W., and A. E. Dunham.1986.Comparative lizards.Copeia 1986:1-18. in lizardreproduction. strategies Tinkle,D. W., H. M. Wilbur,and S. G. Tilley.1970.Evolutionary Evolution24:55-74. in rateoflizards(Sceloporusoccidentalis) ofstandard metabolic Tsuji,J.S. 1988a.Seasonalprofiles Zoology61:230-240. relationto latitude.Physiological latitudes. of metabolism in Sceloporuslizardsfromdifferent 1988b.Thermalacclimation Zoology61:241-253. Physiological andrhynchocephalians. ofsquamates,crocodilians ofpopulations F. B. 1977.The dynamics Turner, Pages 157-264in C. Gans and D. W. Tinkle,eds. BiologyoftheReptilia.Vol. 7. Ecology andbehaviourA. AcademicPress,New York. Pages 229-297in C. Gans andD. Crews,eds. Biology H. 1992.Endogenousrhythms. Underwood, ofChicago brain,andbehavior.University E: hormones, oftheReptilia.Vol. 18.Physiology Press,Chicago. of sprintspeedin Anolis sensitivity of thethermal patterns van Berkum,F. H. 1986.Evolutionary lizards.Evolution40:594-604. of sprintspeed in lizards.American patternsof the thermalsensitivity 1988.Latitudinal 132:327-343. Naturalist ofthe variation Van Damme,R., D. Bauwens,A. M. Castilla,andR. F. Verheyen.1989.Altitudinal inthelizardPodarcistiliguerta. Oecologia(Berlin) performance thermal biologyandrunning 80:516-524. ofthermal physiology: 1990.Evolutionary rigidity VanDamme,R., D. Bauwens,andR. F. Verheyen. lizardLacertavivipara.Oikos57:61-67. thecase ofthecool temperate time andgut-passage foodconsumption offeeding behaviour, dependence 1991.The thermal Ecology5:507-517. in thelizardLacertaviviparaJacquin.Functional differen1992.Incubation temperature VanDamme,R., D. Bauwens,F. Brafia,andR. F. Verheyen. in thelizardPodarcis performance time,eggsurvival,and hatchling hatching tiallyaffects 48:220-228. muralis.Herpetologica size classes,andrelativetailbreaksinthetreelizard,Urosaurus aggregations, Vitt,L. 1974.Winter 30:182-183. ornatus(Sauria:Iguanidae).Herpetologica andfeeding ofbodytemperature S. R., S. Jones,and W. P. Porter.1986.The effect Waldschmidt, in thelizardUta stansburiana. passagetime,and digestivecoefficient regimeon activity, Zoology59:376-383. Physiological eds. Animalenergetics. 1987.Reptilia.Pages 551-619in T. J. Pandianand F. J.Vernberg, Reptilia.AcademicPress,New York. Vol. 2. Bivalviathrough ratesofthelizardUtastansburiana. seasonmortality inactivity variation Wilson,B. 1991.Latitudinal 61:393-414. EcologicalMonographs and ectothermy betweentheenvironment L. C., and C. R. Tracy.1989.Interactions Zimmerman, Zoology62:374-409. in reptiles.Physiological and herbivory Associate Editor: Joel G. Kingsolver This content downloaded from 128.114.163.7 on Thu, 5 Sep 2013 17:33:27 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

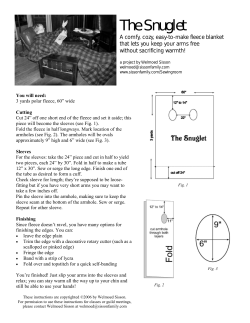

© Copyright 2026