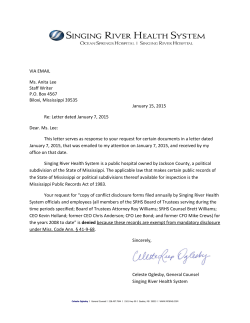

Young ruling PDF