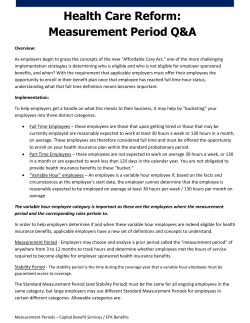

. - The Center for Health and Social Policy