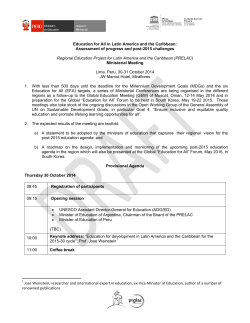

What Happens Now? Time to Deliver the Post