the powerpoint presentation

The Benefits of International Development Initiatives – A Case Study of the Centre for International Development and Training (CIDT) of the University of Wolverhampton. Philip N. Dearden (1) (With contributions from Ella Haruna, Rachel Roland and Mary Surridge) In this short presentation we want to address the question “What benefits can a typical international development centre bring to a university?” As requested, we will be talking from our own personal experiences of actively working in and being involved in the management of a university international development centre for the past 20 years or so. The multidisciplinary centre we are referring to is the Centre for International Development and Training (CIDT) of the University of Wolverhampton. For Details on the Centre see www.wlv.ac.uk/cidt www.wlv.ac.uk/pdf/cidt-brochure.pdf (1) Philip N. Dearden, Head of CIDT, University of Wolverhampton. [email protected] or [email protected] 1 In order to try and make sense of our own very personal experiences we do however want to try and structure these within an academic framework. In September 2013 the UKs Department for Business Innovation and Skills published a very interesting and informative Research Paper (BIS Research Paper 128) entitled the Wider Benefits of International Education in the UK. A wide variety of benefits were identified, which were classified at the highest level by beneficiary and then by type. Benefits for the UK as host country were sub-divided into ‘economic’ and ‘influence’ sub-groups. The ‘internationalisation’ benefit on UK HE institutions and the student community from the presence of international students was interestingly excluded since this would have required wider research, but could, the authors believe, be inferred. The benefit typology in Figure 1 arose from the researcher’s interview information, although, as was noted, this model built upon previous understanding of broad types of impact, particularly de Wit’s rationales for international Higher Education (de Wit, 2002). We have found this “Benefit Typology” helpful and want try and structure our own experiences around a slightly adapted version of this model. However, before we explain the adapted model, we need to introduce you to the Centre that we are talking about and place it within the UK University International Development context. 2 The Centre for International Development and Training (CIDT) of the University of Wolverhampton. The Centre for International Development and Training (CIDT) of the University of Wolverhampton is an International Development Centre with over 40 years track record of managing and supporting poverty reduction programmes and projects in over 130 countries, see www.wlv.ac.uk/cidt and www.wlv.ac.uk/pdf/cidtbrochure.pdf. Although located within the academic framework of the University of Wolverhampton the centre now operates as a Social Enterprise. As we would typically and unashamedly advertise in a bid: The Centre for International Development and Training (CIDT) is a leading centre that provides consultancy and training services in international development. CIDT's strong multi-disciplinary team has a well-established track record of working in over 130 countries during the last 40 years. CIDT is a self-financing, not-for-profit organisation The CIDT operates within an internal company structure and is highly experienced in the contractual, managerial, operational and financial aspects of external, client-funded contracts and projects. This organisational framework means that the CIDT is free to respond quickly and flexibly to clients’ and partners’ needs, whilst maintaining the backing of the University’s financial and personnel support. 3 Within the UK context CIDT is but one of many International Development Centres that focus on what is broadly called Development Studies. Several other notable and longstanding academic departments and teaching/ research centres exist in other Universities, for example: Institute of Development Studies (IDS) University of Sussex http://www.ids.ac.uk/research London School of Economics (LSE) http://www.lse.ac.uk/internationalDevelopment/research/Home.aspx School of International Development, (DEV) University of East Anglia http://www.uea.ac.uk/devresearch/research-themes Centre for Development Studies (CDS) University of Bath http://www.bath.ac.uk/cds/research/ International Development Department (IDD) University of Birmingham http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/government-society/departments/internationaldevelopment/index.aspx School of Environment, Education and Development (SEED) University of Manchester http://www.seed.manchester.ac.uk/research/seedresearch/ The Sheffield Institute for International Development (SIID) University of Sheffield http://siid.group.shef.ac.uk/research/ Bradford Centre for International Development (BCID) University of Bradford http://www.bradford.ac.uk/ssis/bcid/research/ By comparison with these centres the CIDT is much smaller and based in a post 1992 University. To date our focus has been on international development project management and applied consultancy work as opposed to pure academic research and teaching work and this set very much apart from them. Indeed the CIDT has very much kept alive the applied and technical ethos of our former institutional home - Wolverhampton Polytechnic - still fondly called “Wolves Poly” by many former graduates whom we often meet working in developing countries around the world. It is interesting to note that while each individual university will no doubt really appreciate its own international development centre for the teaching and research work they do and their alumnus relations, there appear to have been few studies to examine and/or quantify the wider benefits of such international development centres in the UK beyond those of simply counting international student numbers and by those involved in scoring in the Research Excellence Framework (http://www.ref.ac.uk/pubs/2012-01/). 4 Development Studies (2) is often considered to have started in the postWorld War 2 period with the establishment of the Marshal Plan, the foundation of the United Nations and the International Monetary Fund. However, as has been noted by Homans (2102), the concept of the benefits of international development perhaps date back to the early writings of Jeremy Bentham, an eighteen century philosopher and radical who believed in the decriminalisation of homosexuality and equal rights for women as noted by Dolan (2014). Bentham developed the “greatest happiness principle” (utilitarianism), equality and social justice. He also, interestingly, coined the words “international” and “multicultural” and also foresaw the globalized community in which we now live. As noted by Anyangwe (2012) “internationalisation” in higher education is also not that new. For decades - before there were economic gains to be made from international student recruitment and possibly even before the term was coined - the brightest and wealthiest students from many countries (including developing countries), have gone to study abroad including many who became presidents and chiefs of armed forces for their nations. The international institutions selected have been as much a reflection of the political ties between countries, as they've been an indication of a student's personal ambitions. In addition it’s worth recalling that many students from developing countries were awarded scholarship to enable them to study abroad. The Overseas Development Administration (now renamed as the Department for International Development- DFID) funded many thousands of scholarships through the British Council Technical Cooperation Awards. In the 1970s and 1980s many international development centres in UK (including CIDT) expanded to cope with the demand for international development training. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------(2) Development Studies is a multidisciplinary branch of social science which examines issues related to developing countries, especially concerning social and economic development. Many major UK universities offer degrees in Development Studies and associated subjects. Development Studies can commonly involve Anthropology, Globalisation, Economics, Environment and International Development. 5 Ironically despite all the recent discussion on the internationalisation of Higher Education (British Council 2012, Brandenburg and Hans de Wit 2013, Callan 1993, De Wit 2002, 2012 and 2013, Fielden 2007, Hudzick 2013, Knight 1995 and Woodfield 2010) there seems to have been an almost complete lack of engagement between those involved in “International Development” and those involved in “Internationalisation”. As was passionately noted by Bhandari (2013) experts and practitioners in these two fields really need to speak to each other more. At the present time they barely communicate! This is critically important at a time when many of the economically developed countries now have between 25 and 50% of their populations in Higher Education (Grossman 2012) but globally only a very small percentage of the world’s population (recent estimates are around 7%) actually has access to a Higher Education. http://www.cgci.udg.mx/archivos/Chevening_Fellowship_intro%5B2%5D.p df ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Based on a study conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 24/7 Wall St. compiled a list of the 10 countries with the highest proportion of college-educated adult residents. Topping the charts is Canada — the only nation in the world where more than half its residents can proudly hang college degrees up on their walls. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/05/19/percent-of-world-with-col_n_581807.html 6 At a simple level we can see four key “benefits” of the CIDT. 7 The Perceived benefits from engagement Development initiatives for a University. in International In order to frame and illustrate some of the perceived benefits of the Centre for International Development and Training for our own institution we have slightly adapted the Typology of Benefits Framework (BIZ 2013) discussed above. Figure 2 (below) is an adaptation of the Typology where we have looked at the benefits of CIDT for our own University. 8 We will look at the four core benefits in turn. 1. Economic Benefits to the University. Staff in CIDT have never really felt safe in their jobs. On one level this insecurity provides a great motivation to win business and contracts for the centre yet that motivation is not to achieve a big fat payslip but to take home a normal academic/university administrators salary. On another level it’s a real worry and a job in CIDT is not the job for everyone. Taking a hard-nosed business perspective, as typically our University Director of Finance takes the important point is that CIDT does not lose money. Indeed for the past 25 years CIDT has more than “paid it way” Total income to the University from CIDT over the past 20 years now exceeds £50m. Overheads on all staff salaries have been paid each year to the university. In total over £2m has been paid to the University in the past 20 years. 9 As in most self-financing University centres across the UK arguments over the rates of overheads have raged on for many years and never really been fully resolved. Various differing formulae exist across the sector. Indeed in our own institution we have received very mixed messages about the real importance of “turnover” and/or “surplus” and/or “overheads”. In these days of proving that you are always providing Value for Money (VfM) the issue of university overheads will no doubt continue to occur. Remaining competitive in the market in which we work is sometimes a real struggle with the overheads we have to pay the university. From our perspective we are not actually trying to make a profit (surplus) but fully recognise that we need money for investment in new staff and business development activity in order to continue the work of the centre. In the past five years we have moved toward calling ourselves a Social Enterprise and now actually trade through the Universities new Social Enterprise bank account. This is favored by some organisations especially the UN organizations we work for. 10 Influence – Internal, Local, Regional and National Publicity Internal Influence Case Study 1 – Cultural Awareness Training An example of a benefit of CIDTs international development experience for the wider university comes from some of the recent intercultural sensitivity training we have been undertaking within the University. Staff managing the University of Wolverhampton’s Staff Development Unit (SDU) recognised CIDT’s core staff skills, knowledge and attitudes in relation to intercultural sensitivity. They also knew of the real need for such cultural awareness across all staff in the University. In the past two years the SDU have internally commissioned staff of the CIDT to conduct a series of staff training events on intercultural sensitivity. To date some 400 frontline staff (administrators, caretakers and cleaners) and some 100 academic staff have been trained on a short staff development course. A simple easy-toread Handbook has been produced and made available to all staff. (University of Wolverhampton 2014). 11 Case Study 2 – Continuous Professional Development Project CIDT staff have considerable expertise and experience in designing and conducting Continuous Professional Development programmes. Given this staff from CIDT were asked by the Vice Chancellor to undertake some internal consultancy work to examine the potential for the University to move towards new CPD markets. This six week piece of consultancy work led to a series of some twenty recommendations being made in relation to the design and delivery of Continuous Professional Development Programmes in the University. Case Study 3– Bid R Us As part of our international development work in Nepal CIDT were commissioned to assist a not-for-profit Social enterprise organization with their capacity to develop bids and tenders for development projects. As a result of this work a short handbook entitled “Bids R Us – A Simple Seven Step Guide” was developed. This was subsequently further developed and adapted for use within the University. A one day professional development programme package based on it was further developed to assist staff from other departments successfully bid for external funding. Case Study 4 – LEAD: Leadership and Development. LEAD – “Leadership and Development” is the Universitiy’s senior staff development package. With considerable international leadership experience the Head of CIDT was commissioned as an internal consultant to assist this professional development programme. Working with external consultants from the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education (LFHE) some six cohorts of senior managerial staff from across the institution have now successfully attended the Leadership Programme. Many of these staff are having an influence in their own departments and across the institution and having a real impact on outcomes. 12 Local and Regional Publicity Stories from CIDT have often featured in the University, local and regional press. These press stories often bring the University considerable kudos for the work of CIDT. For example in 2013 the University was awarded a Wolverhampton International Links Association Award for its international work. 13 Graduates and Influence In recent years a smaller number of “hand-picked” grantees have been given Chevening Fellowships for study in the UK. Funded by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) these three-month Fellowships were unashamedly “to help the FCO win friends and influence things”. CIDT was in receipt of two FCO Chevening programmes – the first entitled “Environmental Governance and Democracy”, the second entitled “Government Relations with NGOs and Civil Society”. All Fellows were high achieving experienced mid-level careerists handpicked by the FCO with a view to them having an influence on their return home. Many Chevening Fellows and now in very influential positions back in their own countries. 14 While with us for their 12 week programmes each Chevening Fellow undertook an applied attachment and/or work placement for 2 or 3 weeks. These placements and attachments put us as a Centre in touch with wide range of organisations and many of these contacts led to further work or future placement opportunities for UK students.. 15 Our Continuous Professional Development (CPD) programmes for Development Professionals now span a period of some 40 plus years and many of our graduates have had successful careers following their time in UK or with us on a short course conducted in country. The impact of there CPD programme may be hard to judge quantitatively but its clear that professional development is a often a catalyst for change and career enhancement. 16 National and International Influence The work that CIDT has undertaken has been for a wide range of multilateral and bi-lateral agencies. Over the past twenty years we have worked with many of the large multi-lateral agencies such as the World Bank – International Finance Corporation (IFC), Asian Development Bank (ADB), European Union (EU), FAO, ILO, UNDP, UNEP, UNITAR, UNWRA, UNIDO and the World Health Organisation (WHO). Likewise we have worked with many bilateral agencies including the Department for International Development (DFID), Aus Aid, SNV, FINNIDA, GIZ, JICA NZ Aid, Swiss Development Corporation (SDC). We have also worked with international organisation such as the British Council, Commonwealth Secretariat, CABI, CGIAR, GCARD, FASID, FCO, ICARDA, IDRC, IPGRI, INIBAP and INASP, 17 UK Government Organisations we have worked with include DEFRA, National Health Service, Health Action Zones, Home Office, Renewal Academy, South Yorkshire Regeneration, SYREN, Advantage West Midlands, REGEN West Midlands, Sheffield City Council and Wolverhampton City Council. Private Sector Organisations we have worked with include: Baastel, Cambridge Education Consultants, Cardo Agrisystems, Charles Kendal and Partners, Coffey International, Crown Agents, DAI, Deloitte and Touche, Enterplan, ICF-GHK, Harwelle, HTSPE, IDL, IHSD, LTSI, Mindthe-Gap, Mott MacDonald, KPMG, Options, Price Waterhouse Coopers, Triple Line and WSP. Finally we have worked with a large number of Non-Government Organisations and Civil Society Organisations such as IMMPACT Aberdeen University, Action Aid, IATP, Oxfam, PLAN International, Princes Trust, Red Cross International, Sight Savers, Tearfund, Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO), London School of Economics (LSE) and the International Business Leaders Forum. A large part of our work for these organisation is related to capacity development and again while hard to capture quantitatively we are hopeful that the effects and influence of it are notable. 18 Likewise our work often gives us access to senior staff including Ministers and other politicians. Many of these have been, and are, very influential. We must mention the Rwandan Prime Minister Dr Pierre Damien Habumuremyi who has been very supportive of our work in Rwanda. We must of course give a special mention to Clare Short who for many years was Minister of International Development and responsible for the establishment of DFID and all the massive changes we have seen since 1997. Clare’s early work in DFID set about the required changes and set the target to slow increase international development spending to 0.7% GDP. Only this week has this been fully approved and we are hopeful that on the 1st June 2015 this will be made law. Clare was also a local Birmingham MP and a great supporter of the University. Here she is giving a talk to our Chevening Fellows. Likewise we must also mention Mike Foster who happens to be an Alumni of the University. Here he is, at the University, talking to a group of senior staff from Bangladesh. 19 Benefits to international graduates. Over the past 40 plus years we have had many “graduates” who have left UK with fond memories of CIDT and their own Master’s degree or short Professional Development Programme. We know of many ex-students who have had a big influence in their own countries. A simple case study of in the newly formed country of South Sudan perhaps bests illustrates this. In November 2011 staff from CIDT were asked to undertake some consultancy work in Juba of South Sudan. This opportunity gave us the opportunity to be in direct contact with students who had graduated from our Masters degrees between 3 and 14 years previously to follow up with them and their careers and lives. 20 The two CIDT MScs (I) in Development Education and Training (1993-2003, then (ii) Leadership for Development (2003-2008) were degrees designed for people working in international development and particularly for nationals working in their own country to reduce poverty. CIDT had the chance to co-sponsor some students from Sudan who were working for non-governmental organisations in country, on directly relevant poverty reduction issues. Although CIDT is a selffunding Centre within the University, we waived fees for these students, given the need in Sudan for qualified professionals and they received a small bursary from a University of Wolverhampton students fund, the Steve Biko Trust towards their living costs. Thus CIDT staff have always felt a particular affection for this cohort of students. As borne out by our faith in them, over the years these students made a distinct impression on us because of their passion to build a better tomorrow through public service in their country (now countries) and because of their hard-working, dedicated stance towards the subject matter of international development. The list below shows the current career status of some of them and is up to date as far as is known. Staff have kept in particular touch with three students through the recent violence in South Sudan. Name Nyandeng Malek Deliec Adel Sandrai Ismail Abdulla Lado Charles Loker Margaret Mathiang Joyce Taban Hillary Lohinei Michael Lopidia Mary Lokoyome Elizabeth Awate Lucia Jovani Current whereabouts/job title/role Governor, Warrap State, South Sudan. The first Dinka woman to achieve such leadership status Minister of Education, Science and Technology in Western Equatoria State, South Sudan UNDP Malakal Governance project , South Sudan Ministry of Youth, Sport and Culture, Juba, Board member Manna Sudan. Educational charity, South Sudan Has been the undersecretary in the ministry of Gender, child and social welfare. Member of the National Constitutional Review Commission. Working for AED, South Sudan Livestock officer for FAO, South Sudan Chief of Party, Wildlife Conservation Society officer working alongside Parks people in Jonglei state, South Sudan Working for UNFPA, Juba, South Sudan Working for Sudan Farm, NGO, from Juba, South Sudan UNDP Governance programme, Torit, “Rule of Law” Officer, South Sudan International Development Benefits. In the BIZ 2013 Framework the terminology used in the fourth box was “Benefits to Country of Origin” We have adapted this to “International Development Benefits”. “International Development Benefits” is of course core to CIDTs mission and simply “what we do”. As a self-financing centre all CIDT staff have to be regularly involved in a number of international development initiatives. Some of these are short international development consultancy jobs or capacity development training programmes, some are the management of longer term development programmes. We have chosen four of our larger programmes in three countries to illustrate the impact of our work. All of these progammes, which in total represented a total income of over £25m, involved a series of long and expensive competitive tender processes. The first example we have chosen is that of CIDT’s management and capacity development work for the DFID funded Livelihoods and Forestry Programme in Nepal. Prior to our management of this large (£14.5m) DFID funded programme, CIDT staff had been involved a number of development capacity programmes in Nepal. Indeed we had been involved in Nepal for over 30 years. See http://www.wlv.ac.uk/aboutus/news-and-events/latest-news/2013/april-2013/new-partnership-with-nepaleseenvironmental-specialists.php 22 In 2009 Vijay Shrestha the Deputy Programme Coordinator of the Livelihoods and Forestry Programme (LFP), completed a master’s degree in CIDT at the University of Wolverhampton. Since graduating Vijay has worked with CIDT as the Programme Manager for the Department for International Development funded Livelihoods Forestry Programme. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eI9ZeR929G8 As reported in the DFID Project Completion report in 2013 this development programme successfully generated employment for over 2.8 million people (of whom 85% were poor or excluded people) and helped lift over 1.3 million people out of poverty in Nepal. In order to achieve this Vijay worked tirelessly over the lifetime of the programme leading and inspiring a team of over 130 programme staff - often through insecure times and very difficult political situations in Nepal. Over time the highly successful Livelihoods and Forestry Programme became a "DFID Flagship programme" and was visited by no less than six UK DFID 23 Ministers from Claire Short (2003) through to Andrew Mitchell (2012). 23 In the words of the Head of the Department for International Development in Nepal "the internationally-recognised success of Nepal's community forestry sector recognised globally, owes much to Vijay Shrestha". Vijay has truly inspired and mentored many, ensuring that the next generation of community forestry leaders are ready to take up the challenges ahead. With good management UK Aid (tax payer’s) money from DFID has effectively and efficiently reached the very poorest in Nepal where it has made an enormous difference. Working with CIDT staff at the end of the programme, Vijay helped collate and document all the experiences of the Livelihoods and Forestry programme and these have been published in "A Decade of the Livelihoods and Forestry Programme". http://www.msfp.org.np/uploads/publications/file/A%20Decade%20of%20LFP,2013_2013 0429104434.pdf In 2013 Vijay was awarded the University of Wolverhampton Alumni of the Year Award in the category of “Making the Biggest Contribution to Society”. http://issuu.com/universityofwolverhampton/docs/wlvlife_issue05_-_for_web/23 In 2014 he was made an honorary Doctorate by the university. http://www.wlv.ac.uk/about-us/news-and-events/latest-news/2014/september2014/honour-for-university-graduate.php As was reported in Vijay’s Encomium, his work for the poorest and excluded in Nepal is a wonderful tribute to the real values of the University of Wolverhampton. Of course with reference to the Benefits Typology framework it can be argued that this example of a large international development programme managed by one of our exstudents synergistically hits all four of the core boxes. Clearly some good international development work has been achieved, Clearly Vijay has benefited personally from his Masters degree, and clearly the University has gained both economically and in its influence. Economically CIDT received a management fee for all the work undertaken and the University took its fair share of staff overheads charged on all CIDT staff. In terms of influence it of course hard to measure. However the visit of both our University Chancellor and Vice Chancellor to Nepal to help celebrate the success of the programme helped ensure some of the secondary boxes in the framework were all firmly ticked. This notably includes those of “Influence during capacity development work”, “Promoting Trust and the University Brand” and “Helping build a network of Ambassadors”. 24 Some of the UK based Capacity Development programmes of the Livelihoods and Forestry Programme gave many of our students an opportunity to have a wide influence. Over the past five years a number of our study fellows have attended Chatham House as an integral part of their programme. A number of them have made influential presentations at events at Chatham House. 25 In a similar vein of influence some of our work has lead to real international networking opportunities. For example our work with the Forest Governance Markets and Climate programme over the past five years has given an opportunity to host several annual international gatherings of Civil Society Organisation (CSOs) and Non Government Organizations (NGOs) involved in this important international work. 26 In 2011 a number of CIDT staff were involved the design of an innovative DFID sponsored Climate Fund (the Strategic Climate Institutions Programme SCIP) in Ethiopia. (See http://projects.dfid.gov.uk/project.aspx?Project=201866). Following on from this work CIDT won a grant from ‘CDKN’ to develop a detailed plan as to how a similar innovative fund could work in Rwanda. In 2012 CIDT – as a result of a competitive tendering process - was awarded a £2.5m contract by the Department for International Development to support the operationalization of a national fund for climate and environment over 3 years from October 2012 – September 2015. From 2012 CIDT supported the establishment and operationalization of the Fund and continue to provide ongoing support to the national team that manages the Fund on a daily basis. CIDT identified a team of national staff, and this Fund Management Team ensures that the process of screening projects and disbursing finance is effectively managed. In the initial phases of operationalization, awareness raising and technical assistance to support submission of good proposals was critical. CIDT main activities initially were the staffing and setting up the FONERWA offices, financial systems and grant application processes as well as identifying a pool of call down consultants to provide technical assistance for project development. The purpose of the Fund is to facilitate and coordinate access to domestic, bilateral, multilateral and international climate funding streams and align them with national development programmes that contribute to low carbon development and climate resilient growth in Rwanda. With over $75 million raised through seed capital from the UK Department for International Development, revenue from the Government of Rwanda, and other external finance leveraged, the Fund has potential to change lives with millions of dollars committed across 20 projects. 27 The Fund was officially launched by Prime Minister Anastase Murekezi in October 2014. CIDT continues to provide technical assistance and capacity building for FONERWA, working towards on-going sustainability of the Fund (beyond initial DFID capitalisation). Capacity for managing the Fund is being built ready for full transfer to the Government of Rwanda in September 2015. It becomes increasingly important that results from the Fund are effectively and transparently monitored and lessons disseminated and systems for this are being built and strengthened. Rwanda is highly vulnerable to climate change in terms of increased intensity and unprectability of precipitation on its hilly geography and it’s strongly reliance on rainfed agriculture both for rural livelihoods and its significant exports of tea and coffee. The threat of floods and soil loss and then droughts are very real. The country has experienced a temperature increase of 1.4°C since 1970, higher than the global average. As a cross-sectoral financing mechanism the Fund has the potential for huge impact at the national level, to achieve development objectives of environmentally sustainable, climate resilient and green economic growth. As well as natural resource management in the water catchments encouraging low carbon transport, energy production and architecture in the urban areas in close collaboration with the private sector is a key feature of the fund. It is also ground-breaking on the international stage, attracting a recent visit from a team from the Green Climate Fund (the financial mechanism of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change). 28 Climate compatible development asks policy makers to consider ‘triple win’ strategies that result in low emissions, build resilience and promote development simultaneously. CIDT is leading a further CDKN-funded project to capture, synthesise and share country solutions and best practice emerging from national-level climate change planning in four Africa countries (Ethiopia, Kenya, Mozambique and Rwanda) At least four ‘knowledge’ products per country have been developed, including nationally-owned country reports, case studies and ‘talking heads’ videos from national level climate compatible development planning. During the training of FONEWRA staff and Rwandan consultants (supported by DFID and CDKN) a new Climate Change Rwanda Case study was developed for the CIDT Hand Book “Project and Programme Thinking Tools”. This revised CIDT handbook was used as the core text to teach Project and Programme Management on a three day residential course at Cumberland Lodge to some 80 LSE MSc students 15-18 January 2015. It will be also be used for the training of 50 international Improving Forest Governance participants in CIDT in May/June 2015 (See course Leaflet). Earlier editions of this handbook have been used for the training of staff in DFID, FAO, UNIDO, WTO and many CSOs/NGOs globally. The handbook has also been converted into a new on line training package for the Organisation for Industrial Development of the United Nations and for CIDT. CIDT has been recognised as one of the organizations helping the Government of Rwanda to set the economy on a low carbon and climate resilient development trajectory. FONERWA is showcasing excellence in a highly innovative field, and the FONERWA experience is of great interest to other developing countries and donors. There is a growing recognition amongst both donors and recipients that a coordinated, streamlined approach to climate financing is needed to respond to developing countries’ adaptation and low carbon needs. In the words of President Kagame, “If Rwanda can do it, anyone can do it.” There have already been a number of spinoffs for Rwanda. In recent months the Director General of REMA has agreed to let Rwanda be a laboratory focus for a group of international actors and CIDT will facilitate a south-south learning event in July this year based on the Rwandan experience and sharing of good practice lessons. Beyond CIDT’s influence, Rwanda’s climate change practices have become a leader in the field and often have lesson learning missions from individual countries come to consider how to adapt their successes for their own counties. While the international development impact is yet to really be fully realised the potential influence of the FONERWA programme is already clear to see. Likewise the secondary impact of CIDT’s capacity development work for the University will no doubt be seen in years to come. The Climate and Development Knowledge Network supports decision-makers in designing and delivering climate compatible development. The Climate Development Knowledge Network is managed by an alliance of organisations led by PricewaterhouseCoopers http://www.wlv.ac.uk/media/wlv/pdf/CIDT-Handbook-Thinking-Tools.pdf http://cidt.org.uk/2015-improving-forest-governance-programme/ http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.dfid.gov.uk/Documents/publications/toolsfordevelopment.pdf http://desqie.myzen.co.uk/external/unido/pilot/#home http://desqie.myzen.co.uk/external/cidt/latest/#home 29 Case Study 3 - The Jamaican All Aged School Project (2000 – 2004) and recent Curriculum development work for the Ministry of Education (2012-14). As noted by DFID (2013) education is fundamental to development. A good education is both a human right and an investment for sustainable development. It is a global public good and a necessary ingredient for economic development and poverty reduction. Education enables people to live healthier and more productive lives, allowing them to fulfil their own potential as well as to strengthen and contribute to open, inclusive and economically vibrant societies. Learning propels the transformational potential of education to contribute to better governance, more peace and democracy, political stability and the rule of law. Taken together, evidence suggests that a quality education can enable people to shape, strengthen and contribute to the building blocks of open economies and open societies. Education is also an essential part of responding to current and future challenges, from demographic and climate change, to rising inequalities within and between countries. For education to maximise its transformational potential, children need not only to be in school but also learning. In 2000 Jamaica was facing a learning crisis; too many children in school were learning little or nothing at all. There were many children who were not completing the primary cycle. Responding to this challenge was the Jamaican All Aged School Programme (JAASP). This was a five year DFID funded programme (£3.5m) to assist the 52 poorest schools in Jamaica. 30 The overall Goal of the programme was to improve the lifetime opportunities for poorer rural children. This was measured by an increased number of children from poor communities finding employment or accessing higher levels of education. The specific purpose was simply “Better education for children from poor, rural communities” and this was measured by a series of important indicators. An increase in the number of students reading at or above grade 4 level. An increase in scores attained in core subjects at Grade 6 and 9 levels. An increase in school attendance. An increase in the number of students completing 9 years of schooling. An increase in pupils progressing to secondary school. Huge improvements were made and the programme was jointly considered by the Jamaican Ministry of Education and DFID to be very successful. See http://www2.wlv.ac.uk/webteam/international/cidt/cidt_closertohome.pdf 31 In 2011-15 staff from the CIDT were back in Jamaica working on the Education Transformation Programme, helping facilitate the development of new Primary and Secondary Curricular for the Ministry of Education. This work was funded by the International Development Bank (IADB) The Primary Curriculum (Grades 1-6) and Secondary Curriculum (Grades 7-11) were revised and updated ensuring coherence, progression and alignment between and within all subjects and the development and piloting of three national diagnostic and attainment tests and national school leavers certificate. (Jamaican Curriculum Framework Ministry of Education 2014) The CIDT staff role included planning and review meetings with the Ministry of Education, presentations to the Minister, design of the curriculum framework, wider stakeholder consultation, development of a teacher‐training programme, and the development of piloting protocols and implementation plans. This work led to new updated curricular which are now being piloted in selected schools across the country. 32 Progress on getting children into school has demonstrated what sustained national and international investment can achieve. Clearly however more needs to be done, and sometimes done differently, to ensure all girls and boys can access a quality education and learn. This includes addressing underlying causes of disadvantage, including gender disparities, geographic isolation, disability, ethnic and linguistic disadvantages. While it’s still too early to measure success, the ultimate impact of this new curriculum development work with the Ministry of Education will be for a whole generation of Jamaican children to have a better, more relevant and up to date and challenging education than previously. 33 Conclusions - The need for questioning the current state and role of “Internationalization” and the importance of linking it to International Development now and in the future. The three case studies above have hopefully highlighted the key benefits of “international development” work for Universities. While the benefits maybe clear for some, where does this all leave us in relation to the current “internationalisation” agenda? Since the marketisation of the higher education sector, the rising costs of a university education and the diminishing support of many governments through the public purse, universities - old and new - are rightly or wrongly actively pursuing a range of internationalisation strategies. Indeed it’s been noted that everyone is now talking about internationalisation. The global competition for talents, the emergence of so called “flying faculties”, of international branch campuses, transnational education, the debate on use of agents for recruitment of students, the internationalisation of the curriculum. These topics are not only being debated in the UK but more widely across the globe. 34 European, Northern American and Pacific universities are now all embracing the international agenda. Likewise so are the emerging economies in Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East who have become pro-active in stimulating the internationalisation of their education. The boundaries between resource countries and target countries of internationalisation have, in recent years, become blurred. The new key players in higher education (India, China and Brazil) reflect wider geopolitical shifts and global developments. The positive conclusion one could draw from this picture is that internationalisation is on the rise in higher education. However to still see internationalisation as simply synonymous with international student recruitment is both a limited approach and, as noted by Anyangwe (2012) one now rather loaded with concerns over neocolonialism and imperialism. The international student number “bean counters” in our institutions need to be challenged to think broader and wider. While not denying the importance and good work of international offices in our universities, internationalisation has to rapidly move out of these offices and become part of curriculum development, quality assurance and faculty development. Likewise we need to move away from extractive research and speak more of real international partnerships based on some real solid principles. Qatar, Singapore, the United Arab Emirates and China have all promoted internationalisation in national policy, including inviting prestigious foreign universities to establish local campuses. In all cases, for students in the host country, this form of education is likely to be more accessible and cheaper than travelling to the UK or the US, while still allowing them to benefit from an institution’s high “brand value”. 35 Finally those of us working in International Development in Higher Education need to be asking critical questions about the broader implications and relevance of our own home institutional internationalisation agendas. We need to urge others to start moving away from simple international recruitment to genuinely providing solutions for global, national or community-level problems. While those of us involved in international development may be relatively good at guiding those in our own areas of work (see for example Geddes (2015)) we need to think broader. We need to consider for example to what extent are we guiding our future internationally mobile students to think about the Education for All initiative or the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) or the new forthcoming Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a frame of reference for selecting their future course of study and professional careers? Of course the personal selection of a place and/or field of study will ultimately be an individual one, driven by personal and professional aspirations. We do perhaps however have a role to play in shaping the next generation's thinking about how their learning can help solve some of the world's most pressing development problems. We need to question and carefully consider how we can help future students receive the right learning outcomes that make them ready for a world that is more and more interculturally and internationally connected. 36 For this all to actually happen we believe that firstly need to rethink and redefine our current understanding of internationalisation and really consider international development as an integral part of it. Looking to the future this simply has to be the case. As has now clearly been demonstrated by a number of demographers (World Population Trends 2050 Economist 2012) virtually all population growth in the future will be in the “less developed countries”. This may be a case of back to the future where over time the term “Internationalisation” may well actually come to mean “international development”. 37 Clearly looking ahead the future is clear. All internationalized universities need to be looking towards Asia and then increasingly towards Africa. This means international development will be key. 38 In conclusion its clear to us looking briefly at the dramatic demographic predictions of the future that “internationalization” and “international development” MUST be linked. The sub title of this conference is “The Competitive Edge”. If we are to keep that competitive edge two things are required: Firstly all our universities really do need to be producing “global citizens” who have a real understanding of International Development and its importance. This of course includes the important topics of equality, “the bottom billion” and sustainability. Secondly we need to be aware that in the future if students from developing countries do not come to UK, USA and/or European institutions then we may well collectively start “losing out” to the new rising universities in countries like India and China who may well start offering real benefits of their own to students and of course may well be backed by real incentives from their own increasingly powerful 39 governments. 39 40 41

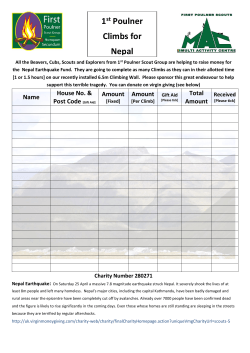

© Copyright 2026