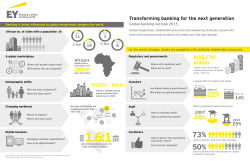

Competition between Organizational Forms