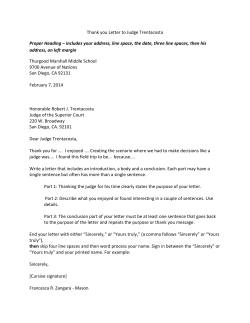

Annual report - curia